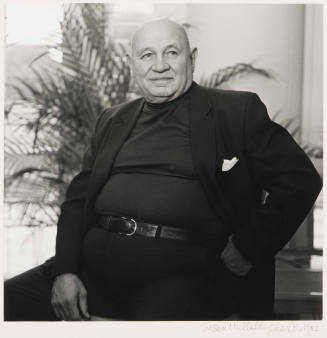

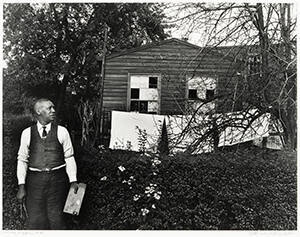

Skip to main contentBiographyElihu Vedder (1836–1923) lived an unconventional life and produced work that was highly individual and imaginative—sometimes even sublime, mysterious, and haunting. Called a visionary artist even during his lifetime, he created paintings and drawings that often invite comparisons with the British artist William Blake.

Vedder was born in New York City; his family, of old Dutch stock, had roots in the area dating back to the seventeenth century. His father worked in both New York and Cuba as a dentist, and young Elihu spent long periods of time as a child and youth in the Caribbean with his family. He was an unenthusiastic student who longed to draw; his father first attempted to apprentice him to an architect but eventually allowed him to study with painter Tompkins Harrison Matteson, who specialized in genre and history painting. Vedder had little other formal training before he left, at age twenty, for Europe. He stayed in Europe for four years, studying first in Paris and then in Italy, a country he would love for the rest of his life.

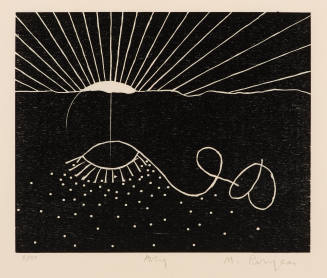

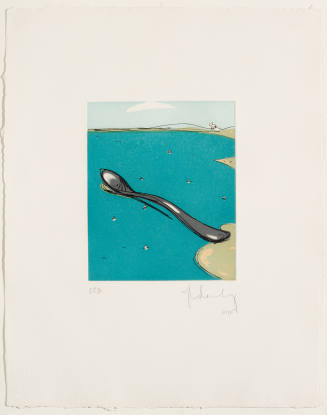

After four years, his father withdrew his financial support, forcing Vedder to return to the United States at the outbreak of the Civil War. An old hunting injury to his left arm kept him out of military service; instead, he worked as an illustrator in New York City. [1] It was at this time that he produced some of his strangest and most memorable paintings. In The Questioner of the Sphinx, 1863, an emaciated man approaches a half-buried sphinx in the desert, his desperation palpable as he leans in to hear the sphinx’s secrets. In The Lair of the Sea Serpent, 1864, the peaceful calm of a beautiful deserted beach is made eerily threatening when the viewer perceives the terrifying sea serpent draped across the dunes. The Lost Mind, 1864–1865, presents a young woman wandering unseeing and devoid of reason through an otherworldly landscape. These paintings brought him new attention from critics and patrons in New York and especially in Boston, where his work was very well received. He was elected a full member of the National Academy of Design in 1865.

After the war, Vedder returned to Italy. He married Caroline (Carrie) Rosenkrans in 1869. It was a time of great happiness for the artist, and the haunting scenes of the 1860s became less common. He and his wife were part of the vibrant community of American and British expatriates in Rome. They had a new baby. And they traveled, spending months at a time in England, where Vedder made the acquaintance of members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. [2] His work at this time, highly detailed and decorative, with subjects drawn from legend and mythology, reflected the influence of those British artists. Vedder’s sources for inspiration, however, were always quite varied and diverse, from the Italian Renaissance to Biblical stories to literary sources such as The Arabian Nights.

In 1884, Vedder was commissioned to produce drawings to accompany a new translation of The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam. The publication was an instant success, catapulting Vedder to fame and bringing him financial reward for the first time in his life. The windfall eventually allowed him to purchase a villa in Capri called the Villa dei Quattro Venti. [3] The energetic artist was far from retired, however. He was commissioned in 1894 to produce a mural for Bowdoin College and, in 1896, a series for the Library of Congress. The style of Vedder’s murals has sometimes been called early Art Nouveau. The mural commissions placed him in good company with other artists of note who were also producing murals in the late nineteenth century, such as John La Farge, Abbott Henderson Thayer, Edwin Howland Blashfield, and John Singer Sargent.

Vedder spent his later years writing his autobiography, The Digressions of V, published in 1910, and enjoying his villa in Capri. He died in 1923. Although the American Academy of Arts and Letters honored him with an exhibition in 1937, he received little scholarly attention until later in the twentieth century. In 1957, art historian Regina Soria discovered a cache of letters, documents, and drawings in Italy. The discovery eventually led in the 1960s to an exhibition, the publication of Vedder’s biography, and later to new attention from other scholars in the field. [4]

A visionary artist of prodigious talent, Elihu Vedder looked to the past for inspiration, deftly absorbed the styles and themes of his contemporaries, and produced innovative work that anticipated future artistic movements.

Notes:

[1] Frank Jewett Mather, Estimates in Art: Sixteen Essays on American Painters of the Nineteenth Century (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1931), 76.

[2] Regina Soria, Elihu Vedder: American Visionary Artist in Rome (Rutherford, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1970), 62 and 71.

[3] Mather, Estimates in Art, 85.

[4] Joshua C. Taylor, et al., Perceptions and Evocations: The Art of Elihu Vedder (Washington, DC: Published for the National Collection of Fine Arts by the Smithsonian Institution Press, 1979), viii. Soria describes the discovery in this way: “After [Vedder’s] marriage, he settled in Rome near the Piazza di Spagna and lived there for over fifty years. And there the vast hoard of his drawings and correspondence remained until I came along. Since Vedder’s death in 1923, the fond d’atelier of this American painter in Rome had been sitting in trunks in an apartment above the Caffè Greco. …I was told that when I was ready to consider Vedder I should go to Via Condotti and call on the family living in the apartment just above the Caffè Greco. They were the Vedder heirs and they welcomed me, offering to let me go through the whole fond d’atelier. I was the only person from the United States who had inquired of them about Vedder since the Second World War. The bulk of the Vedder material was kept in the country and I was invited to go and inspect it. So in July 1958 I made my way to the remotest village in the Sabine Mountains. …Vedder’s work [sketches, letters, writings] was all over the house.” Soria, Elihu Vedder, 3-5.

Elihu Vedder

1836 - 1923

Vedder was born in New York City; his family, of old Dutch stock, had roots in the area dating back to the seventeenth century. His father worked in both New York and Cuba as a dentist, and young Elihu spent long periods of time as a child and youth in the Caribbean with his family. He was an unenthusiastic student who longed to draw; his father first attempted to apprentice him to an architect but eventually allowed him to study with painter Tompkins Harrison Matteson, who specialized in genre and history painting. Vedder had little other formal training before he left, at age twenty, for Europe. He stayed in Europe for four years, studying first in Paris and then in Italy, a country he would love for the rest of his life.

After four years, his father withdrew his financial support, forcing Vedder to return to the United States at the outbreak of the Civil War. An old hunting injury to his left arm kept him out of military service; instead, he worked as an illustrator in New York City. [1] It was at this time that he produced some of his strangest and most memorable paintings. In The Questioner of the Sphinx, 1863, an emaciated man approaches a half-buried sphinx in the desert, his desperation palpable as he leans in to hear the sphinx’s secrets. In The Lair of the Sea Serpent, 1864, the peaceful calm of a beautiful deserted beach is made eerily threatening when the viewer perceives the terrifying sea serpent draped across the dunes. The Lost Mind, 1864–1865, presents a young woman wandering unseeing and devoid of reason through an otherworldly landscape. These paintings brought him new attention from critics and patrons in New York and especially in Boston, where his work was very well received. He was elected a full member of the National Academy of Design in 1865.

After the war, Vedder returned to Italy. He married Caroline (Carrie) Rosenkrans in 1869. It was a time of great happiness for the artist, and the haunting scenes of the 1860s became less common. He and his wife were part of the vibrant community of American and British expatriates in Rome. They had a new baby. And they traveled, spending months at a time in England, where Vedder made the acquaintance of members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. [2] His work at this time, highly detailed and decorative, with subjects drawn from legend and mythology, reflected the influence of those British artists. Vedder’s sources for inspiration, however, were always quite varied and diverse, from the Italian Renaissance to Biblical stories to literary sources such as The Arabian Nights.

In 1884, Vedder was commissioned to produce drawings to accompany a new translation of The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam. The publication was an instant success, catapulting Vedder to fame and bringing him financial reward for the first time in his life. The windfall eventually allowed him to purchase a villa in Capri called the Villa dei Quattro Venti. [3] The energetic artist was far from retired, however. He was commissioned in 1894 to produce a mural for Bowdoin College and, in 1896, a series for the Library of Congress. The style of Vedder’s murals has sometimes been called early Art Nouveau. The mural commissions placed him in good company with other artists of note who were also producing murals in the late nineteenth century, such as John La Farge, Abbott Henderson Thayer, Edwin Howland Blashfield, and John Singer Sargent.

Vedder spent his later years writing his autobiography, The Digressions of V, published in 1910, and enjoying his villa in Capri. He died in 1923. Although the American Academy of Arts and Letters honored him with an exhibition in 1937, he received little scholarly attention until later in the twentieth century. In 1957, art historian Regina Soria discovered a cache of letters, documents, and drawings in Italy. The discovery eventually led in the 1960s to an exhibition, the publication of Vedder’s biography, and later to new attention from other scholars in the field. [4]

A visionary artist of prodigious talent, Elihu Vedder looked to the past for inspiration, deftly absorbed the styles and themes of his contemporaries, and produced innovative work that anticipated future artistic movements.

Notes:

[1] Frank Jewett Mather, Estimates in Art: Sixteen Essays on American Painters of the Nineteenth Century (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1931), 76.

[2] Regina Soria, Elihu Vedder: American Visionary Artist in Rome (Rutherford, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1970), 62 and 71.

[3] Mather, Estimates in Art, 85.

[4] Joshua C. Taylor, et al., Perceptions and Evocations: The Art of Elihu Vedder (Washington, DC: Published for the National Collection of Fine Arts by the Smithsonian Institution Press, 1979), viii. Soria describes the discovery in this way: “After [Vedder’s] marriage, he settled in Rome near the Piazza di Spagna and lived there for over fifty years. And there the vast hoard of his drawings and correspondence remained until I came along. Since Vedder’s death in 1923, the fond d’atelier of this American painter in Rome had been sitting in trunks in an apartment above the Caffè Greco. …I was told that when I was ready to consider Vedder I should go to Via Condotti and call on the family living in the apartment just above the Caffè Greco. They were the Vedder heirs and they welcomed me, offering to let me go through the whole fond d’atelier. I was the only person from the United States who had inquired of them about Vedder since the Second World War. The bulk of the Vedder material was kept in the country and I was invited to go and inspect it. So in July 1958 I made my way to the remotest village in the Sabine Mountains. …Vedder’s work [sketches, letters, writings] was all over the house.” Soria, Elihu Vedder, 3-5.

Person TypeIndividual