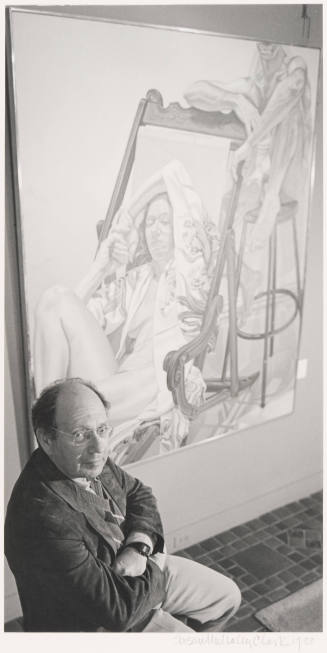

Skip to main contentBiographyUnlike many of her peers, Audrey Flack (born 1931) chose to become a realist and figurative painter despite artistic training in modernism and its predominant style, Abstract Expressionism. Flack was born and raised in New York City, and like most of her artistic generation, she pursued a university and art school education. Selected as one of ten students by the renowned modernist Josef Albers for the Bachelor of Fine Arts program at Yale University, Flack was schooled in abstraction but, outside of the art school environment, made representational images. After returning to New York City following graduation, she studied anatomy with Robert Beverly Hale at the Art Students League and continued to produce figurative work. [1] She began to exhibit in the early 1960s, about the same time that she married and started a family, and she often represented her daughters in her art. During this period she was torn by her artistic ambition, her need to work, and challenging familial responsibilities including an autistic child. [2]

Initially Flack based her paintings on art historical images, followed by still life paintings featuring contemporary household products. She soon began to employ photographs exclusively as sources for her paintings. Throughout the 1960s, Flack used images from news magazines, including one of President Kennedy’s motorcade in Dallas, as well as images of other world leaders and social protest marches.

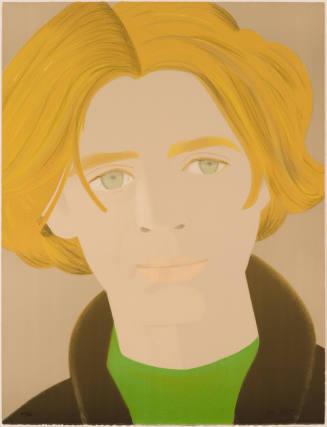

Flack’s first work in the style later known as Photorealism was the Farb Family Portrait of 1969–70. Photorealism emerged in the mid-1960s as an offshoot of Pop Art and was influential as a style in both painting and sculpture throughout the 1970s. Among the leading figures of Photorealism were Chuck Close, Robert Cottingham, Ben Schonzeit, Richard Estes, Malcolm Morley, and Duane Hanson. All worked directly from photographs, either transferring the image by means of the grid system onto large canvases or projecting it directly on to the painting’s surface and then painting in the projected forms. Many of these artists came to Photorealism after rejecting the grandiose and highly individualized mark making of Abstract Expressionism. The Photorealists adopted a low-key approach in their technical and extremely life-like representations of otherwise ordinary subject matter. Like the Abstract Expressionists, these artists worked on a large scale and emphasized the overall surface of the canvas. [3]

For the Farb Family Portrait, Flack took multiple photographs of the Farbs, selected one from the group, and then used a slide projector to transfer the image directly onto the canvas. She showed a sense of humor by painstakingly creating a trompe l’oeil gilt frame on the portrait, complete with a brass plate listing the title, date, and artist’s name. In her Photorealist works, Flack moved away from linear drawing to working with rich, saturated hues, building up color areas and reflective material surfaces. She learned to use an airbrush, a commercial painting tool that allowed her to mix and apply color in a way that produced a different intensity of hues than she could produce with a traditional paintbrush.

Flack shared an interest in highly reflective surfaces and everyday objects with the other Photorealists but increasingly created works that were referential, personal, and symbolic. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, she produced a series of architectural and sculptural works before turning almost exclusively to still life paintings. Art critics at the time dismissed her depiction of commercially available beauty products such as lipsticks, cologne, jewelry, and other feminine articles as being in poor taste. [4] Feminist critics were initially negative as well, perhaps regarding the inclusion of cosmetics and jewelry as an endorsement of women’s subordination to men. Since then, these still life paintings have come to be understood as far more complex images that may in fact privilege a woman’s point of view. [5] Although she has worked primarily in bronze figurative sculpture since the early-to mid-eighties, Flack remains best known for her Photorealist paintings, now hanging in collections around the world.

Notes:

[1] Samantha Baskind, “Everyone thought I was Catholic: Audrey Flack’s Jewish Identity,” American Art 23, no.1 (Spring 2009): 104–115.

[2] Adrienne M. Golub, “Against All Odds: Suffering and Healing are Reconciled in the Feminist Art of Audrey Flack,” Creative Loafing, April 1, 2004, http://tampa.creativeloafing.com/gyrobase/against_all_odds.

[3] Stéphanie Molinard, Double Take: Photorealism from the 1960s and ’70s. (Waltham, MA: The Rose Art Museum of Brandeis University, 2005): 5.

[4] Charlotte Streifer Rubinstein, review of Breaking the Rules: Audrey Flack, a Retrospective 1950–1990, by Thalia Gouma-Peterson, et al. Woman’s Art Journal 15, no. 1 (Spring–Summer 1994): 42.

[5] Katherine Hauser, “Audrey Flack’s Still Lifes: Between Femininity and Feminism,” Woman’s Art Journal 22, no. 2 (Autumn 2001–Winter 2002): 1, 26–30.

Audrey Flack

born 1931

Initially Flack based her paintings on art historical images, followed by still life paintings featuring contemporary household products. She soon began to employ photographs exclusively as sources for her paintings. Throughout the 1960s, Flack used images from news magazines, including one of President Kennedy’s motorcade in Dallas, as well as images of other world leaders and social protest marches.

Flack’s first work in the style later known as Photorealism was the Farb Family Portrait of 1969–70. Photorealism emerged in the mid-1960s as an offshoot of Pop Art and was influential as a style in both painting and sculpture throughout the 1970s. Among the leading figures of Photorealism were Chuck Close, Robert Cottingham, Ben Schonzeit, Richard Estes, Malcolm Morley, and Duane Hanson. All worked directly from photographs, either transferring the image by means of the grid system onto large canvases or projecting it directly on to the painting’s surface and then painting in the projected forms. Many of these artists came to Photorealism after rejecting the grandiose and highly individualized mark making of Abstract Expressionism. The Photorealists adopted a low-key approach in their technical and extremely life-like representations of otherwise ordinary subject matter. Like the Abstract Expressionists, these artists worked on a large scale and emphasized the overall surface of the canvas. [3]

For the Farb Family Portrait, Flack took multiple photographs of the Farbs, selected one from the group, and then used a slide projector to transfer the image directly onto the canvas. She showed a sense of humor by painstakingly creating a trompe l’oeil gilt frame on the portrait, complete with a brass plate listing the title, date, and artist’s name. In her Photorealist works, Flack moved away from linear drawing to working with rich, saturated hues, building up color areas and reflective material surfaces. She learned to use an airbrush, a commercial painting tool that allowed her to mix and apply color in a way that produced a different intensity of hues than she could produce with a traditional paintbrush.

Flack shared an interest in highly reflective surfaces and everyday objects with the other Photorealists but increasingly created works that were referential, personal, and symbolic. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, she produced a series of architectural and sculptural works before turning almost exclusively to still life paintings. Art critics at the time dismissed her depiction of commercially available beauty products such as lipsticks, cologne, jewelry, and other feminine articles as being in poor taste. [4] Feminist critics were initially negative as well, perhaps regarding the inclusion of cosmetics and jewelry as an endorsement of women’s subordination to men. Since then, these still life paintings have come to be understood as far more complex images that may in fact privilege a woman’s point of view. [5] Although she has worked primarily in bronze figurative sculpture since the early-to mid-eighties, Flack remains best known for her Photorealist paintings, now hanging in collections around the world.

Notes:

[1] Samantha Baskind, “Everyone thought I was Catholic: Audrey Flack’s Jewish Identity,” American Art 23, no.1 (Spring 2009): 104–115.

[2] Adrienne M. Golub, “Against All Odds: Suffering and Healing are Reconciled in the Feminist Art of Audrey Flack,” Creative Loafing, April 1, 2004, http://tampa.creativeloafing.com/gyrobase/against_all_odds.

[3] Stéphanie Molinard, Double Take: Photorealism from the 1960s and ’70s. (Waltham, MA: The Rose Art Museum of Brandeis University, 2005): 5.

[4] Charlotte Streifer Rubinstein, review of Breaking the Rules: Audrey Flack, a Retrospective 1950–1990, by Thalia Gouma-Peterson, et al. Woman’s Art Journal 15, no. 1 (Spring–Summer 1994): 42.

[5] Katherine Hauser, “Audrey Flack’s Still Lifes: Between Femininity and Feminism,” Woman’s Art Journal 22, no. 2 (Autumn 2001–Winter 2002): 1, 26–30.

Person TypeIndividual