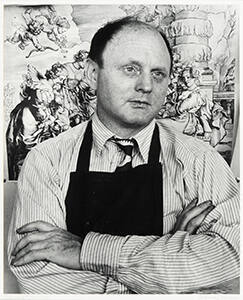

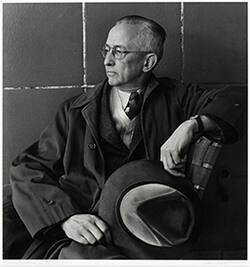

Skip to main contentBiographyAn artist of enormous natural talent, Joseph Stella’s most important role was as an ambassador of European-style modernism in the United States. Born in Italy, Stella (1877–1946) immigrated to America at the age of eighteen. [1] He was sponsored and supported by his older brother, who was a successful physician in Greenwich Village and a prominent member of the Italian-American community in New York. Joseph Stella briefly studied medicine and pharmacology, but he soon persuaded his brother to let him turn his attention to art. The young artist studied at the Art Students League and at William Merritt Chase’s New York School of Art, copying Old Masters and drawing from life. He worked for a time as an illustrator, often for reform-minded journals and papers.

In 1909, he returned to Europe, where he sketched and painted in Italy and immersed himself in the community of avant-garde artists in Paris. He was increasingly drawn to Cubism and to the work of the Italian Futurists, and his work reflected this new interest. His shift from careful copies of Old Masters to Cézanne-inspired still lifes to near-abstract city scenes was remarkably swift.

Stella returned to New York in 1913 and participated in the Armory Show. His aesthetic breakthrough came after a nighttime bus ride to Coney Island. In his mind, the lights at the bright amusement park appeared to be battling each other. The artistic result of this impression was the shockingly abstract painting Battle of Lights, Coney Island, Mardi Gras, 1913–1914, collection of Yale University Art Gallery. The painting captures Stella’s impression of the cacophony of the amusement park at night, with fleeting images of electric lights and attractions jumbled together and juxtaposed with each other. Exhibited in New York in a group show organized by Arthur B. Davies, the painting caused a sensation.

In New York, Stella mingled with a group of cosmopolitan New York Dada artists that included Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray. Although Stella himself was fiercely independent and never applied labels such as “Dada” or “Futurist” to himself, the contemporary press repeatedly associated him with these avant-garde circles.

Even after Stella had achieved some success as a fine artist, he continued his work as an illustrator for reformist journals. In 1918, he was assigned to industrial sites in Pennsylvania, where he found himself drawn to the depiction of the machines and products of modern industry. His move to Brooklyn inspired a fascination with the Brooklyn Bridge, which coincided with a change in his style. Rather than the disorderly mass of disparate motifs and text that made up Battle of Lights, Brooklyn Bridge, 1919–1920, collection of Yale University Art Gallery, was characterized by a strong central axis, an insistent verticality, sweeping lines, and Cubist-inspired patches of black, red, and blue. The strong central axis recalls an altarpiece with a crucifix at its center, and, indeed, Stella invested the bridge with mystical properties: “Seen for the first time, as a metallic weird Apparition under a metallic sky, out of proportion with the winged lightness of its arch, traced for the conjunction of WORLDS, supported by the massive dark towers dominating the surrounding tumult of the surging skyscrapers with their gothic majesty sealed in the purity of their arches, the cables, like divine messages from above, transmitted to the vibrating coils, cutting and dividing into innumerable musical spaces the nude immensity of the sky, it impressed me as the shrine containing all the efforts of the new civilization of AMERICA.” [2] The artist’s celebration of this icon of American modernism conveyed his conviction that the machine was a harbinger of progress.

Stella’s interest in the Brooklyn Bridge continued for decades. Clearly inspired by Futurism, the artist more and more eschewed modeling and shading in the later bridge paintings. At the same time, perhaps inspired by an extended sojourn in Italy between 1926 and 1934, the artist’s iconography expanded to include organic elements from the natural world and figures from classical mythology and Catholicism. Marked by clean lines, flat colors, and stylized compositions, these traditional artistic subjects were transformed by the artist’s modernist aesthetic. The magnified flowers, plants, and trees recall similar work by Georgia O’Keeffe, while the religious images anticipated the surreal mysticism of Frida Kahlo.

Political tensions in Europe forced Stella’s return to the United States in 1934. Upon his return, he experienced both personal and professional difficulties. Often egotistical and combative, he found himself cut off from the artists and friends with whom he had associated in the 1910s and 1920s. Critical reaction to his work, which at the time was marked by stylized but representational imagery, was decidedly mixed. He sought employment with mural projects and the Works Progress Administration but found it difficult to procure a steady income. Perhaps because of his unstable financial circumstances, he briefly reconciled with his long-estranged wife, but the reunion was short-lived. Plagued by ill health, Stella became increasingly isolated and anxious. He died in 1946.

Critics and scholars have tended to focus on Stella’s Brooklyn Bridge series as the pinnacle of his artistic achievement and have been more critical of his later figural work. A retrospective at the Whitney Museum of Art in 1963, at the height of abstraction’s popularity in America, was largely unsuccessful. Subsequent retrospectives at the Whitney Museum and elsewhere have worked to revive the artist’s reputation and to spark interest in both his early and later work. In spite of these controversies, Stella’s groundbreaking role in the introduction of modernism to America has secured his artistic legacy.

Notes:

[1] See Barbara Haskell, Joseph Stella (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., in association with the Whitney Museum of American Art, 1994).

[2] Stella, quoted in Haskell, Joseph Stella, 86.

Joseph Stella

1877 - 1946

In 1909, he returned to Europe, where he sketched and painted in Italy and immersed himself in the community of avant-garde artists in Paris. He was increasingly drawn to Cubism and to the work of the Italian Futurists, and his work reflected this new interest. His shift from careful copies of Old Masters to Cézanne-inspired still lifes to near-abstract city scenes was remarkably swift.

Stella returned to New York in 1913 and participated in the Armory Show. His aesthetic breakthrough came after a nighttime bus ride to Coney Island. In his mind, the lights at the bright amusement park appeared to be battling each other. The artistic result of this impression was the shockingly abstract painting Battle of Lights, Coney Island, Mardi Gras, 1913–1914, collection of Yale University Art Gallery. The painting captures Stella’s impression of the cacophony of the amusement park at night, with fleeting images of electric lights and attractions jumbled together and juxtaposed with each other. Exhibited in New York in a group show organized by Arthur B. Davies, the painting caused a sensation.

In New York, Stella mingled with a group of cosmopolitan New York Dada artists that included Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray. Although Stella himself was fiercely independent and never applied labels such as “Dada” or “Futurist” to himself, the contemporary press repeatedly associated him with these avant-garde circles.

Even after Stella had achieved some success as a fine artist, he continued his work as an illustrator for reformist journals. In 1918, he was assigned to industrial sites in Pennsylvania, where he found himself drawn to the depiction of the machines and products of modern industry. His move to Brooklyn inspired a fascination with the Brooklyn Bridge, which coincided with a change in his style. Rather than the disorderly mass of disparate motifs and text that made up Battle of Lights, Brooklyn Bridge, 1919–1920, collection of Yale University Art Gallery, was characterized by a strong central axis, an insistent verticality, sweeping lines, and Cubist-inspired patches of black, red, and blue. The strong central axis recalls an altarpiece with a crucifix at its center, and, indeed, Stella invested the bridge with mystical properties: “Seen for the first time, as a metallic weird Apparition under a metallic sky, out of proportion with the winged lightness of its arch, traced for the conjunction of WORLDS, supported by the massive dark towers dominating the surrounding tumult of the surging skyscrapers with their gothic majesty sealed in the purity of their arches, the cables, like divine messages from above, transmitted to the vibrating coils, cutting and dividing into innumerable musical spaces the nude immensity of the sky, it impressed me as the shrine containing all the efforts of the new civilization of AMERICA.” [2] The artist’s celebration of this icon of American modernism conveyed his conviction that the machine was a harbinger of progress.

Stella’s interest in the Brooklyn Bridge continued for decades. Clearly inspired by Futurism, the artist more and more eschewed modeling and shading in the later bridge paintings. At the same time, perhaps inspired by an extended sojourn in Italy between 1926 and 1934, the artist’s iconography expanded to include organic elements from the natural world and figures from classical mythology and Catholicism. Marked by clean lines, flat colors, and stylized compositions, these traditional artistic subjects were transformed by the artist’s modernist aesthetic. The magnified flowers, plants, and trees recall similar work by Georgia O’Keeffe, while the religious images anticipated the surreal mysticism of Frida Kahlo.

Political tensions in Europe forced Stella’s return to the United States in 1934. Upon his return, he experienced both personal and professional difficulties. Often egotistical and combative, he found himself cut off from the artists and friends with whom he had associated in the 1910s and 1920s. Critical reaction to his work, which at the time was marked by stylized but representational imagery, was decidedly mixed. He sought employment with mural projects and the Works Progress Administration but found it difficult to procure a steady income. Perhaps because of his unstable financial circumstances, he briefly reconciled with his long-estranged wife, but the reunion was short-lived. Plagued by ill health, Stella became increasingly isolated and anxious. He died in 1946.

Critics and scholars have tended to focus on Stella’s Brooklyn Bridge series as the pinnacle of his artistic achievement and have been more critical of his later figural work. A retrospective at the Whitney Museum of Art in 1963, at the height of abstraction’s popularity in America, was largely unsuccessful. Subsequent retrospectives at the Whitney Museum and elsewhere have worked to revive the artist’s reputation and to spark interest in both his early and later work. In spite of these controversies, Stella’s groundbreaking role in the introduction of modernism to America has secured his artistic legacy.

Notes:

[1] See Barbara Haskell, Joseph Stella (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., in association with the Whitney Museum of American Art, 1994).

[2] Stella, quoted in Haskell, Joseph Stella, 86.

Person TypeIndividual