Skip to main content

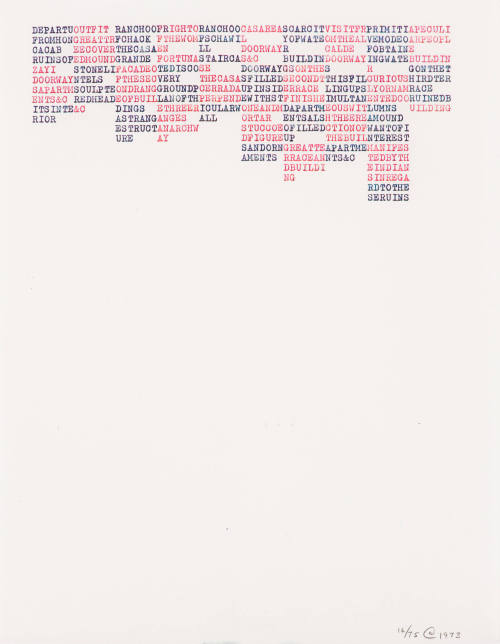

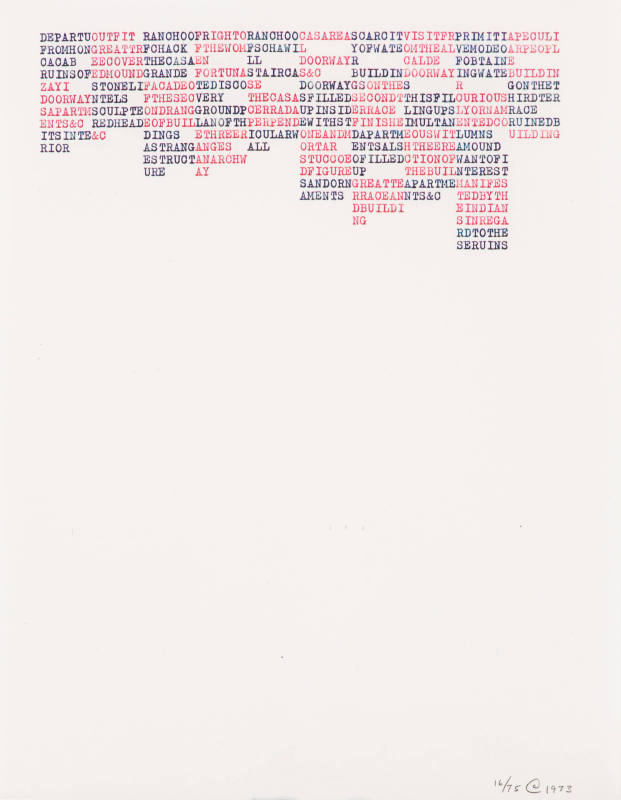

The poem-page Yucatan, Andre’s contribution to the 1982 Anthology Film Archives portfolio, perfectly exemplifies Minimalism in its production while seemingly departing from the style in its actual and symbolic representation of a landscape through text. This text-landscape, while mechanically produced by means of a typewriter, suggests a subjective experience of an archeological site. With a little effort, an English-speaking viewer can organize the letters into words, and the words into phrases. Transcribed, it reads:

DEPARTU FROM HONCACAB RUINS OF ZAYI DOORWAYS APARTMENTS & C ITS INTERIOR OUTFIT GREAT TREECOVERED MOUND STONE LINTELS SCULPTED HEAD RANCHO OF CHACK THE CASA GRANDE FACADE OF THE SECOND RANGE OF BUILDINGS A STRANGE STRUCTURE FRIGHT OF THE WOMEN FORTUNATE DISCOVERY GROUND PLAN OF THE THREE RANGES AN ARCHWAY RANCHO OF SCHAWILL STAIRCASE THE CASA CERRADA PERPENDICULAR WALL CASA REAL DOORWAYS &C DOORWAYS FILLED UP INSIDE WITH STONE AND MORTAR STUCCOED FIGURES AND ORNAMENTS SCARCITY OF WATER BUILDINGS ON THE SECOND TERRACE FINISHED APARTMENTS ALSO FILLED UP GREAT TERRACE AND BUILDING VISIT FROM THE ALCALDE DOORWAYS THIS FILLING UP SIMULTANEOUS WITH THE ERECTION OF THE BUIL APARTMENTS &C PRIMITIVE MODE OF OBTAINING WATER CURIOUSLY ORNAMENTED COLUMNS AROUND WANT OF INTEREST MANIFESTED BY THE INDIANS IN REGARD TO THESE RUINS A PECULIAR PEOPLE BUILDING ON THE THIRD TERRACE RUINED BUILDING

In fact, the poem-page/ text-landscape has been directly appropriated by Andre from the table of contents in Volume II of John L. Stephens’s Incidents of Travel in Yucatan, published by Harper & Brothers, New York, in 1848. The excerpt is as below:

CHAPTER I.

Departure from Nohcacab.—Outfit.—Ranch of Chack.—Fright of the Women.—Rancho of Schawill—Casa Real.—Scarcity of Water.—Visit from the Alcalde.—Primitive Mode of obtaining Water.—A peculiar People.—Ruins of Zayi.—Great tree-covered Mound.—The Casa Grande.—Fortunate Discovery.—Staircase.—Doorways, &c.—Buildings on the second Terrace.—Doorways.—Curiously ornamented Columns.—Building on the third Terrace.—Doorways, Apartments &c.—Stone Lintels.—Façade of the second Range of Buildings.—Ground Plan of the three Ranges.—The Casa Cerrada.—Doorways filled up inside with Stone and Mortar.—Finished Apartments, also filled up.—This filling up simultaneous with the Erection of the Building.—A Mound.—Ruined Building.—Its Interior.—Sculptured Head, &c.—A strange Structure.—An Archway.—Perpendicular Wall.—Stuccoed Figures and Ornaments.—Great Terrace and Building.—Apartments, &c.—Want of Interest manifested by the Indians in regard to these Ruins.

Comparing the texts, it seems that Andre rearranged the order of the chapter descriptions for formal reasons, i.e., to fit into his columns, since there does not seem to be an appreciable difference in meaning between Andre’s version and the original. The obscure source in a nineteenth-century travelogue and its mechanical reproduction render the final image as somewhat, if not wholly, arbitrary. Did Andre in fact ever travel to Mexico? Did he read Stephens’s book? How can the viewer evaluate this artwork if its apparent meaning is meaningless?

Yucatan is a print in that it had an original matrix—a sheet of paper that was typed using a manual typewriter. It was then reproduced on a Xerox color copier. Andre signed and dated the lower right corner in 1973, but it seems that the edition numbering 16/75 would date the print from 1982, as the Anthology portfolio notes indicate. Andre used both red and black typewriter ribbons, and planned his compositional typing carefully. Letters are placed into vertical columns, with regular color changes of black to red so that the non-legible aspect of the print resembles a partial checkerboard. The print’s coloration does not seem to have any organizing principle other than giving it a geometric, or checkerboard, appearance which is typical of Andre’s work. There are random text breaks that activate the page’s negative space and emulate the contour of cliffs or ruins to suggest a crumbling edifice of words.

Rob Weiner, curator and art historian at the Chinati Foundation in Marfa, Texas, explains: “Andre designed the shape of poetry according to his own understanding of the word as a concrete module, similar to the squares of industrial metal, wooden timbers, or bricks in his signature three-dimensional pieces. His poems don’t always incorporate complete sentences, phrases or even associative terms, but use words sequentially. Shaped text functions as both pattern and poem—visual art and literature simultaneously.” [2]

Notes:

[1] Stella quoted in Lawrence Rubin, Frank Stella: Paintings 1958 to 1965, a Catalogue Raisonné (New York: Stewart, Tabori & Chang, 1986), 18, and Andre quoted in Dorothy Miller, Sixteen Americans (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1959), 76.

[2] Rob Weiner, “On Carl Andre’s poems,” The Chinati Foundation website, http://www.chianti.org

ProvenanceFrom 1984

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC, given by the American Art Foundation through The Pace Gallery, New York on March 20, 1984. [1]

Notes:

[1] Letter, March 20, 1984, object file.

Exhibition History2007-2008

Word Play: Text and Modern Art

Reynolda House Museum of American Art (11/13/ 2007-5/4/2008)

2016-2018

Off the Wall: Postmodern Art at Reynolda

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC (12/3/2016-6/11/2018)

Published References

DepartmentAmerican Art

Yucatan

Artist

Carl Andre

(1935 - 2024)

Date1982

MediumXerox pages

DimensionsFrame: 13 3/4 x 11 3/4 in. (34.9 x 29.8 cm)

Paper: 11 x 8 1/2 in. (27.9 x 21.6 cm)

Image (approximate): 3 x 7 1/8 in. (7.6 x 18.1 cm)

SignedCA (monogram) 1973

Credit LineGift of the American Art Foundation

Copyright© 2021 Carl Andre / Licensed by VAGA at Artist Rights Society (ARS), NY

Object number1984.2.1.b

DescriptionCarl Andre, along with fellow sculptors Donald Judd, Robert Morris, Dan Flavin, and Sol Lewitt, is unfailingly named as a major minimalist artist. Minimalism emerged during the post-Abstract Expressionism period and was most crucial during the 1960s and 1970s, although some practitioners continue to work as minimalists. Unlike its contemporary movement, Conceptual Art, Minimalism emphasized the physical properties of art materials, the mechanics of art production, and the absence of extrinsic meaning in the artwork. As Andre’s friend Frank Stella famously said, “What you see is what you see,” a phrase reiterated by Andre’s statement, “Art excludes the unnecessary.” [1] For the most part, minimalist artists created gallery or temporary installations. Similar to Conceptual Art, Minimalism was deliberately avant-garde and rejected traditional art practices which idolize the artist as genius, stress the special or unique qualities of a fine art object, and employ illusionistic or other facile techniques in production. Andre assembled his sculptures using factory-made bricks arranged in unvarying patterns, stacked pre-cut lumber in pyramidal forms, gathered studio pedestals and leaned them against gallery walls, and scattered building tiles randomly on a gallery floor. Yet somewhat unexpectedly Andre—who prefers to be called an art worker and has spoken of insight gained from physical labor when he worked on the Pennsylvania Railroad—has written poetry from a young age.The poem-page Yucatan, Andre’s contribution to the 1982 Anthology Film Archives portfolio, perfectly exemplifies Minimalism in its production while seemingly departing from the style in its actual and symbolic representation of a landscape through text. This text-landscape, while mechanically produced by means of a typewriter, suggests a subjective experience of an archeological site. With a little effort, an English-speaking viewer can organize the letters into words, and the words into phrases. Transcribed, it reads:

DEPARTU FROM HONCACAB RUINS OF ZAYI DOORWAYS APARTMENTS & C ITS INTERIOR OUTFIT GREAT TREECOVERED MOUND STONE LINTELS SCULPTED HEAD RANCHO OF CHACK THE CASA GRANDE FACADE OF THE SECOND RANGE OF BUILDINGS A STRANGE STRUCTURE FRIGHT OF THE WOMEN FORTUNATE DISCOVERY GROUND PLAN OF THE THREE RANGES AN ARCHWAY RANCHO OF SCHAWILL STAIRCASE THE CASA CERRADA PERPENDICULAR WALL CASA REAL DOORWAYS &C DOORWAYS FILLED UP INSIDE WITH STONE AND MORTAR STUCCOED FIGURES AND ORNAMENTS SCARCITY OF WATER BUILDINGS ON THE SECOND TERRACE FINISHED APARTMENTS ALSO FILLED UP GREAT TERRACE AND BUILDING VISIT FROM THE ALCALDE DOORWAYS THIS FILLING UP SIMULTANEOUS WITH THE ERECTION OF THE BUIL APARTMENTS &C PRIMITIVE MODE OF OBTAINING WATER CURIOUSLY ORNAMENTED COLUMNS AROUND WANT OF INTEREST MANIFESTED BY THE INDIANS IN REGARD TO THESE RUINS A PECULIAR PEOPLE BUILDING ON THE THIRD TERRACE RUINED BUILDING

In fact, the poem-page/ text-landscape has been directly appropriated by Andre from the table of contents in Volume II of John L. Stephens’s Incidents of Travel in Yucatan, published by Harper & Brothers, New York, in 1848. The excerpt is as below:

CHAPTER I.

Departure from Nohcacab.—Outfit.—Ranch of Chack.—Fright of the Women.—Rancho of Schawill—Casa Real.—Scarcity of Water.—Visit from the Alcalde.—Primitive Mode of obtaining Water.—A peculiar People.—Ruins of Zayi.—Great tree-covered Mound.—The Casa Grande.—Fortunate Discovery.—Staircase.—Doorways, &c.—Buildings on the second Terrace.—Doorways.—Curiously ornamented Columns.—Building on the third Terrace.—Doorways, Apartments &c.—Stone Lintels.—Façade of the second Range of Buildings.—Ground Plan of the three Ranges.—The Casa Cerrada.—Doorways filled up inside with Stone and Mortar.—Finished Apartments, also filled up.—This filling up simultaneous with the Erection of the Building.—A Mound.—Ruined Building.—Its Interior.—Sculptured Head, &c.—A strange Structure.—An Archway.—Perpendicular Wall.—Stuccoed Figures and Ornaments.—Great Terrace and Building.—Apartments, &c.—Want of Interest manifested by the Indians in regard to these Ruins.

Comparing the texts, it seems that Andre rearranged the order of the chapter descriptions for formal reasons, i.e., to fit into his columns, since there does not seem to be an appreciable difference in meaning between Andre’s version and the original. The obscure source in a nineteenth-century travelogue and its mechanical reproduction render the final image as somewhat, if not wholly, arbitrary. Did Andre in fact ever travel to Mexico? Did he read Stephens’s book? How can the viewer evaluate this artwork if its apparent meaning is meaningless?

Yucatan is a print in that it had an original matrix—a sheet of paper that was typed using a manual typewriter. It was then reproduced on a Xerox color copier. Andre signed and dated the lower right corner in 1973, but it seems that the edition numbering 16/75 would date the print from 1982, as the Anthology portfolio notes indicate. Andre used both red and black typewriter ribbons, and planned his compositional typing carefully. Letters are placed into vertical columns, with regular color changes of black to red so that the non-legible aspect of the print resembles a partial checkerboard. The print’s coloration does not seem to have any organizing principle other than giving it a geometric, or checkerboard, appearance which is typical of Andre’s work. There are random text breaks that activate the page’s negative space and emulate the contour of cliffs or ruins to suggest a crumbling edifice of words.

Rob Weiner, curator and art historian at the Chinati Foundation in Marfa, Texas, explains: “Andre designed the shape of poetry according to his own understanding of the word as a concrete module, similar to the squares of industrial metal, wooden timbers, or bricks in his signature three-dimensional pieces. His poems don’t always incorporate complete sentences, phrases or even associative terms, but use words sequentially. Shaped text functions as both pattern and poem—visual art and literature simultaneously.” [2]

Notes:

[1] Stella quoted in Lawrence Rubin, Frank Stella: Paintings 1958 to 1965, a Catalogue Raisonné (New York: Stewart, Tabori & Chang, 1986), 18, and Andre quoted in Dorothy Miller, Sixteen Americans (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1959), 76.

[2] Rob Weiner, “On Carl Andre’s poems,” The Chinati Foundation website, http://www.chianti.org

ProvenanceFrom 1984

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC, given by the American Art Foundation through The Pace Gallery, New York on March 20, 1984. [1]

Notes:

[1] Letter, March 20, 1984, object file.

Exhibition History2007-2008

Word Play: Text and Modern Art

Reynolda House Museum of American Art (11/13/ 2007-5/4/2008)

2016-2018

Off the Wall: Postmodern Art at Reynolda

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC (12/3/2016-6/11/2018)

Published References

Status

Not on view