Skip to main content

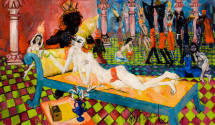

Ancient Queen is a multi-figured exotic scene dominated by a diagonally placed chaise, on which reclines a thin, white-skinned woman dressed only in red panties and an elaborate headdress. She holds in her hand a green snake; a black attendant stands behind her. In the background are many partially nude white and black figures, some sitting while others dance or perform a ritual. The floor throughout consists of several colorful checkerboard patterns with intersecting and conflicting perspectives. The back wall is red on the left and blue on the right. A series of eight pink Egyptian-like columns are scattered in the background and reiterate the thin vertical proportions of the figures who in their stances resemble Egyptian wall paintings. The whole painting is a riot of saturated colors, often defined by black outlines. Contributing to the visual lushness of the painting is the loose application of paint.

The subject of Ancient Queen is the impending suicide of the notorious Egyptian queen, Cleopatra. Known as a seductress of powerful men, her reign was characterized by political intrigue. Although Cleopatra was only thirty-nine at her death, Evergood shows her as a vain but aging woman. With large black eyes she gazes off in the distance, while she contemplates the asp—the instrument of her death—in her claw-like hand. In front of her is a prison-like box that once contained the snake, and a bright blue vase of lilies with intensely red stamens, which in traditional altarpieces are symbols of purity, a virtue foreign to Cleopatra. [2] She wears a glistening and gold-colored variant of the pharaoh’s crown.

Rather than choosing to portray Cleopatra in her role as a ruler, Evergood presented her as a beautiful and sensuous but ultimately pathetic woman. His work often featured women with exaggerated proportions, with large breasts and buttocks, underdressed, like lingerie advertisements. His interest in female bodies may have been nurtured by his wife’s career as a professional dancer and teacher, and, in keeping with this theory, many background figures in Ancient Queen appear to be dancing. Because of his penchant for grotesqueness, Evergood was often viewed as a satirist, but he saw his art differently: “For thirty years, I have been using human situations graphically, perhaps in a similar manner to that which Chaplin does cinematographically, to try and entertain, but at the same time to explore the cavities of decay, and to try and build up little anthill islands of hope.”[3]

Ancient Queen is reminiscent of two well-known precedents: Edouard Manet’s Olympia and Henri Matisse’s Blue Nude. Like the former, Evergood’s painting shows a pale white woman on a couch attended from behind by a black servant. Whereas Olympia is a modern courtesan who looks out at the viewer in a blasé fashion, Cleopatra is an historical figure contemplating her fate. Matisse’s Blue Nude depicts an artist’s model, rendered with an African-inspired savagery, and resembles Evergood’s painting in its emphasis on the exotic. Of the three, Ancient Queen is the busiest and most vividly colorful. Evergood explained his unusual and expressionistic approach to color: “It’s done, with me, by closing my eyes and knowing the color, feeling the color in my brain that I want to use—the nasty color or sickly color, the sweet color, or violent color, or pretty-pretty-dolly color that will express the mood of what I’m trying to put over. I’m not a calculating painter, and it’s not an analytical process.” [4]

The canvas is boldly signed at the bottom center, under the couch: Philip Evergood LX, and barely visible underneath it and a layer of paint is a smaller signature. These dual autographs, along with an uneven paint application, probably indicate that the painting was begun as early as the mid-1930s when Evergood was painting most of his historical subjects. It was not unusual for him to put aside canvases and return to them at a later time. The completed Ancient Queen is dated 1960, the year of Evergood’s retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art, although it was not included in the exhibition. By necessity, the artist would have had to review earlier work for the exhibition and may have hoped his career would enjoy a resurgence. In a 1968 interview, after Abstract Expressionism and during the heyday of Pop and Minimalism, he alluded to what he saw as the emptiness of contemporary art movements: “I have always been interested in expressing ideas not from an illustrative standpoint but to me a painting with a great idea back of it is greater than a fine painting with nothing back of it.”[5]

Notes:

[1] Evergood, “Sure, I’m a Social Painter,” Magazine of Art, November 1943, 254–259, reprinted in David Shapiro, ed. Social Realism: Art as a Weapon (New York: Frederick Ungar Publishing Company, 1973), 158, and Evergood, note, March 1966, Philip Evergood Papers, quoted in Kendall Taylor, Philip Evergood: Never Separate from the Heart (London and Toronto: Bucknell University Press and Associated University Presses, 1986), 176.

[2] Charles C. Eldredge, Barbara Babcock Millhouse, and Robert G. Workman, American Originals: Selections from Reynolda House, Museum of American Art (New York: Abbeville Press, 1990), 124.

[3] Evergood, speech at Bridgewater Public Library, Connecticut, October 1964, Philip Evergood Papers, quoted in Taylor, Philip Evergood, 148.

[4] Evergood interview with John I.H. Baur, Philip Evergood (New York: Abrams, 1978), 68.

[5] Evergood interview with Forrest Selvig, December 3, 1968, Archives of American Art, http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-philip-evergood-12410

ProvenanceBefore 1972

Mr. and Mrs. Louis Smith [1]

1972

Sale, Sotheby Parke Bernet, Inc., New York, “20th Century American Paintings, Sculpture, Watercolors, and Drawings,” no. 102, May 24, 1972. [2]

After 1972

Kennedy Galleries, Inc. [3]

After 1976

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC. Given by Lawrence A. Fleischman of Kennedy Galleries, Inc. [4]

Notes:

[1] Kennedy Galleries provenance. See Object File.

[2] Auction Record. See Object File.

[3] See Note 1.

[4] See Note 1.

Exhibition History1962

Philip Evergood: Paintings, Drawings

ACA Galleries, New York

Cat. No. 3

1964

Philip Evergood

Gallery 63, New York

Lent by Mrs. Blanche Smith

1969

Philip Evergood, Painter of Ideas

Gallery of Modern Art, New York

Cat. No. 63 (as Death of a Queen)

1972

Important American Art/1903-1972

Kennedy Galleries, Inc., New York

Cat. No. 42

1973

A Selection of 20th Century American Masterpieces

Kennedy Galleries, Inc., New York

Cat. No. 16

1974

Memorial Exhibition, Eugene Berman, Philip Evergood, John Folinsbee, Anna Hyatt Huntington, Jacques Lipchits, Franklin Watkins

American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York

Cat. No. 6

1990-1992

American Originals, Selected Paintings from Reynolda House Museum of American Art

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC (9/22/1990-4/26/1992)

Published ReferencesMillhouse, Barbara B. and Robert Workman. American Originals. New York: Abbeville Press Publishers, 1990: 124-125.

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Reynolda: Her Muses, Her Stories , with contributions by Martha R. Severens and David Park Curry (Winston-Salem, N.C.: Reynolda House Museum of American Art affiliated with Wake Forest University, 2017). pg.144, 145, 200

DepartmentAmerican Art

Ancient Queen

Artist

Philip Evergood

(1901 - 1973)

Date1961

Mediumoil on canvas

DimensionsFrame (unverified): 39 1/4 x 59 in. (99.7 x 149.9 cm)

Image (unverified): 28 x 48 in. (71.1 x 121.9 cm)

SignedPhilip Evergood LX

Credit LineGift of Lawrence A. Fleischman, Kennedy Galleries, Inc.

CopyrightPublic Domain

Object number1976.2.7

DescriptionIn November 1943, Philip Evergood published an article, “Sure, I’m a Social Painter,” in which he addressed the tendency of artists to brag about themselves and bemoaned the paucity of critics among the large number of artists. While citing the importance of formal elements, he claimed: “all good art throughout the ages has been a social art. And because good art of the past has portrayed human beings and their habits, it has constituted the most pleasing record of that past that exists.” Evergood frequently depicted historical and Biblical themes, using them as metaphors for the present. “The world today is distorted, unreal, ugly, violent, and destructive.” [1]Ancient Queen is a multi-figured exotic scene dominated by a diagonally placed chaise, on which reclines a thin, white-skinned woman dressed only in red panties and an elaborate headdress. She holds in her hand a green snake; a black attendant stands behind her. In the background are many partially nude white and black figures, some sitting while others dance or perform a ritual. The floor throughout consists of several colorful checkerboard patterns with intersecting and conflicting perspectives. The back wall is red on the left and blue on the right. A series of eight pink Egyptian-like columns are scattered in the background and reiterate the thin vertical proportions of the figures who in their stances resemble Egyptian wall paintings. The whole painting is a riot of saturated colors, often defined by black outlines. Contributing to the visual lushness of the painting is the loose application of paint.

The subject of Ancient Queen is the impending suicide of the notorious Egyptian queen, Cleopatra. Known as a seductress of powerful men, her reign was characterized by political intrigue. Although Cleopatra was only thirty-nine at her death, Evergood shows her as a vain but aging woman. With large black eyes she gazes off in the distance, while she contemplates the asp—the instrument of her death—in her claw-like hand. In front of her is a prison-like box that once contained the snake, and a bright blue vase of lilies with intensely red stamens, which in traditional altarpieces are symbols of purity, a virtue foreign to Cleopatra. [2] She wears a glistening and gold-colored variant of the pharaoh’s crown.

Rather than choosing to portray Cleopatra in her role as a ruler, Evergood presented her as a beautiful and sensuous but ultimately pathetic woman. His work often featured women with exaggerated proportions, with large breasts and buttocks, underdressed, like lingerie advertisements. His interest in female bodies may have been nurtured by his wife’s career as a professional dancer and teacher, and, in keeping with this theory, many background figures in Ancient Queen appear to be dancing. Because of his penchant for grotesqueness, Evergood was often viewed as a satirist, but he saw his art differently: “For thirty years, I have been using human situations graphically, perhaps in a similar manner to that which Chaplin does cinematographically, to try and entertain, but at the same time to explore the cavities of decay, and to try and build up little anthill islands of hope.”[3]

Ancient Queen is reminiscent of two well-known precedents: Edouard Manet’s Olympia and Henri Matisse’s Blue Nude. Like the former, Evergood’s painting shows a pale white woman on a couch attended from behind by a black servant. Whereas Olympia is a modern courtesan who looks out at the viewer in a blasé fashion, Cleopatra is an historical figure contemplating her fate. Matisse’s Blue Nude depicts an artist’s model, rendered with an African-inspired savagery, and resembles Evergood’s painting in its emphasis on the exotic. Of the three, Ancient Queen is the busiest and most vividly colorful. Evergood explained his unusual and expressionistic approach to color: “It’s done, with me, by closing my eyes and knowing the color, feeling the color in my brain that I want to use—the nasty color or sickly color, the sweet color, or violent color, or pretty-pretty-dolly color that will express the mood of what I’m trying to put over. I’m not a calculating painter, and it’s not an analytical process.” [4]

The canvas is boldly signed at the bottom center, under the couch: Philip Evergood LX, and barely visible underneath it and a layer of paint is a smaller signature. These dual autographs, along with an uneven paint application, probably indicate that the painting was begun as early as the mid-1930s when Evergood was painting most of his historical subjects. It was not unusual for him to put aside canvases and return to them at a later time. The completed Ancient Queen is dated 1960, the year of Evergood’s retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art, although it was not included in the exhibition. By necessity, the artist would have had to review earlier work for the exhibition and may have hoped his career would enjoy a resurgence. In a 1968 interview, after Abstract Expressionism and during the heyday of Pop and Minimalism, he alluded to what he saw as the emptiness of contemporary art movements: “I have always been interested in expressing ideas not from an illustrative standpoint but to me a painting with a great idea back of it is greater than a fine painting with nothing back of it.”[5]

Notes:

[1] Evergood, “Sure, I’m a Social Painter,” Magazine of Art, November 1943, 254–259, reprinted in David Shapiro, ed. Social Realism: Art as a Weapon (New York: Frederick Ungar Publishing Company, 1973), 158, and Evergood, note, March 1966, Philip Evergood Papers, quoted in Kendall Taylor, Philip Evergood: Never Separate from the Heart (London and Toronto: Bucknell University Press and Associated University Presses, 1986), 176.

[2] Charles C. Eldredge, Barbara Babcock Millhouse, and Robert G. Workman, American Originals: Selections from Reynolda House, Museum of American Art (New York: Abbeville Press, 1990), 124.

[3] Evergood, speech at Bridgewater Public Library, Connecticut, October 1964, Philip Evergood Papers, quoted in Taylor, Philip Evergood, 148.

[4] Evergood interview with John I.H. Baur, Philip Evergood (New York: Abrams, 1978), 68.

[5] Evergood interview with Forrest Selvig, December 3, 1968, Archives of American Art, http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-philip-evergood-12410

ProvenanceBefore 1972

Mr. and Mrs. Louis Smith [1]

1972

Sale, Sotheby Parke Bernet, Inc., New York, “20th Century American Paintings, Sculpture, Watercolors, and Drawings,” no. 102, May 24, 1972. [2]

After 1972

Kennedy Galleries, Inc. [3]

After 1976

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC. Given by Lawrence A. Fleischman of Kennedy Galleries, Inc. [4]

Notes:

[1] Kennedy Galleries provenance. See Object File.

[2] Auction Record. See Object File.

[3] See Note 1.

[4] See Note 1.

Exhibition History1962

Philip Evergood: Paintings, Drawings

ACA Galleries, New York

Cat. No. 3

1964

Philip Evergood

Gallery 63, New York

Lent by Mrs. Blanche Smith

1969

Philip Evergood, Painter of Ideas

Gallery of Modern Art, New York

Cat. No. 63 (as Death of a Queen)

1972

Important American Art/1903-1972

Kennedy Galleries, Inc., New York

Cat. No. 42

1973

A Selection of 20th Century American Masterpieces

Kennedy Galleries, Inc., New York

Cat. No. 16

1974

Memorial Exhibition, Eugene Berman, Philip Evergood, John Folinsbee, Anna Hyatt Huntington, Jacques Lipchits, Franklin Watkins

American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York

Cat. No. 6

1990-1992

American Originals, Selected Paintings from Reynolda House Museum of American Art

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC (9/22/1990-4/26/1992)

Published ReferencesMillhouse, Barbara B. and Robert Workman. American Originals. New York: Abbeville Press Publishers, 1990: 124-125.

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Reynolda: Her Muses, Her Stories , with contributions by Martha R. Severens and David Park Curry (Winston-Salem, N.C.: Reynolda House Museum of American Art affiliated with Wake Forest University, 2017). pg.144, 145, 200

Status

Not on viewCollections