Skip to main content

The subject of Keith, is Keith Hollingworth (born 1937), a sculptor and painter, who had been an art department faculty member at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, where Close taught from 1965 to 1967. In an interview Close recalled his move to Soho: “A friend of mine at UMass … Keith Hollingworth (who’s the Keith that I painted)—came to New York at the same time. He already had a loft and he helped us find our loft. Our first loft was on Greene Street between Canal and Grant. 2000 square feet. That was $150 a month and that was considered top dollar for loft space.” [1]

In the first decade of his professional career, Close was using. almost exclusively, airbrush technology to create his works. With Keith/Mezzotint, he returned to working directly by hand and incorporated a grid. The grid system became part of his artistic investigation; his process consisted of abstract mark making, even though the final result was representational. Throughout the 1970s, the artist produced work in various media and used his signature grid format to take a small photograph and blow it up on large canvases or sheets of paper. With his 1972 print, Keith/Mezzotint, Close left his working grid visible and subsequently became very intrigued with the artistic device itself. The image itself, Keith’s face, is not a portrait, and one does not gain any insight into his personality. By making each grid square, each increment no more important than any other and simultaneously essential to and independent of the overall representational image, Close becomes an abstract artist. “I came of age in the 1960s, when minimal, reductive and process issues were certainly in the air. …That is something I was always aware of, and it interested me a great deal. I really did believe that process would set you free. Instead of having to dream up a great idea—waiting for the clouds to part and a bolt of lightning to strike your skull—you are better off just getting to work. In the process of making things, ideas will come to you.”[2]

In addition, he became extremely inventive in how he filled out his grid. “I started doing fingerprint pieces, which were an outgrowth of the dot pieces. They started out to be stamped into the spaces of the grid in the same way the dots had been sprayed into the center of each grid—left to right, top to bottom, regular marks. The fingerprint is like the dot around the mark, so then the little corners of each square were blank. So then I started to do things like cut clear plastic masks that I could put over the drawing, see through the clear plastic, see the context in which the mark was made, stamp the square fingerprint so it was like a brick that built the whole space. … Now, with the finger paintings, it was possible for everyone to see just how physical an experience it was. The physicality was very important and the personal mark. This is my actual body.” [3]

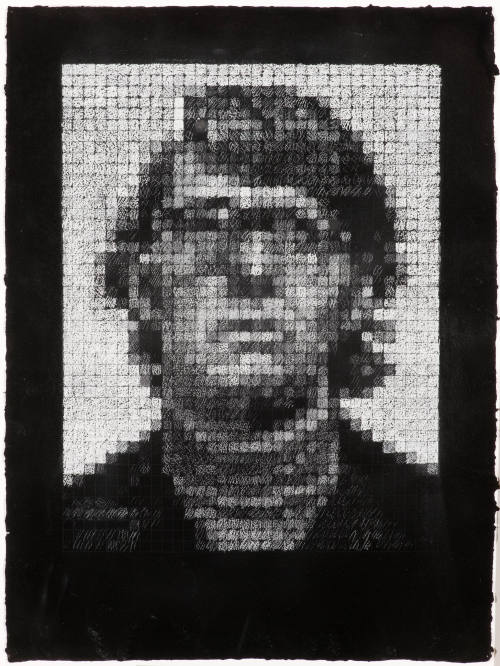

In the Keith/Six Drawing series, he repeats his black-and-white image in the same size, altering only the physical means of mark-making to either fill in grid squares or in the case of Keith/Random Fingerprint Version, eschewing the grid altogether. Yet the six images are very distinct from each other and the differences between them simply result from a variation in technique. The key to Keith/White Conté Version is the inversion of the usual relationship of black on white, which is reminiscent of Close’s notable printmaking achievement in 1972 with Keith/Mezzotint, the photograph rendered as a mezzotint engraving. With additional marks of the conté crayon, Close built up his highlights and it is the paper support itself that provides the darkest shading. Here the artist began by preparing the sheet by painting it with black gouache, then drawing in white conté crayon. Seemingly drawing in reverse to create a full range of values, the artist’s application of the conté creates the lightest shades in the composition.

The overall image is quite distinct from the others in the series, as Terri Sultan explains: “Take any small detail from the six images of Keith/Six Drawing Series, where Close represented the same ‘Keith’ at the same scale in six different techniques of analysis and transfer. The chosen detail will prove to be different in each image, not only because the medium is different but because the internal structure has shifted ever so slightly to accommodate the immediate set of graphic and tonal relationships within the local context of the sheet. Look closely, in fact, at any Close illusion. Suddenly, even in full color and continuous tone, it won’t look naïve, unaltered, or natural.” [4]

Addressing the issue of his methodology, Close explained on one occasion: “Some people wonder whether what I do is inspired by a computer and whether or not that kind of imaging is a part of what makes this work contemporary. I absolutely hate technology, and I’m computer illiterate, and I never use any laborsaving devices although I’m not convinced that a computer is a laborsaving device. I’m very much about slowing things down and making every decision myself. But, there’s no question that life in the twentieth century is about imaging. It is about photography. It is about film. And it is about new digitalized things. There are layers of similarity, I suppose, that have to do with the way computer-generated imagery is made from scanning. I scan the photograph as well, and I break it down into incremental bits, and they can break it down into incremental bits. In fact, I have a Scientific American from 1973 that I saw on a newsstand the exact day that I was walking to my first dot drawing show at Bykert Gallery. Clearly, there are some similar issues, but I had no idea that it existed. ” [5]

Reynolda House Museum of American Art acquired the Keith/Six Drawing Seriesin 1979 with funds provided by the National Endowment for the Arts, matched by R. J. Reynolds Industries, Inc. The grant stipulated that any works purchased were to be by living American artists. The museum’s Founding President, Barbara Babcock Millhouse, recalls consulting with then Whitney Museum of American Art curator Patterson Sims, who recommended that any acquisitions reflect the museum’s strength in representational art. At the time, the predominant style in this vein was Photorealism. Close was oftentimes associated with this group, but had distinguished himself by his greatly enlarged realistic images, which were built up from incremental abstract marks. Close has requested that Keith/Six Drawing Series be displayed and reproduced as a single work, which affirms it as an extended exploration of creative processes of the initial photograph. [6]

Notes:

[1] Close interview with Jud Tully, May 14–September 30, 1987, New York. Archives of American Art, http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-chuck-close-13141

[2] Terrie Sultan, Chuck Close Prints: Process and Collaboration (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press and Blaffer Gallery, the Art Museum of the University of Houston, 2003), 132.

[3] Close interview with Jud Tully, Archives of American Art.

[4] Sultan, Chuck Close Prints, 23.

[5] Close quoted in Robert Storr, Chuck Close, exhibition catalogue (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1998), 99.

[6] Object file, Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

ProvenanceFrom 1980

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC, purchased from the Pace Gallery, New York, NY on March 27, 1980 [1]

Notes:

[1] Invoice, object file.

Exhibition History1998-1999

Chuck Close

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY (2/25/1998-5/26/1998)

Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, IL (6/20/1998-9/13/1998)

Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C. (10/15/1998-1/10/1999)

Seattle Art Museum, Seattle, WA (2/18/1999-5/9/1999)

Hayward Gallery, London, England (7/22/1999-9/19/1999)

2003

Self and Soul: The Architecture of Intimacy

Asheville Art Museum at Pack Place, Asheville, NC (3/2003-5/2003)

2006

Self/Image: Portraiture from Copley to Close

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC (8/30/2006-12/30/2006)

2009

Chuck Close: The Keith Series

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC (1/17/2009-5/31/2009)

Published ReferencesChuck Close: Recent Paintings (New York: Pace Wildenstein, 1995).

Storr, Robert. Chuck Close (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2002).

Batchelder, Ann. Self and Soul: The Architecture of Intimacy (Asheville, NC: Asheville Art Museum, 2003).

Photorealism (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1980).

DepartmentAmerican Art

Keith/White Conte

Artist

Chuck Close

(American, 1940 - 2021)

Date1979

Mediumwhite Conté crayon, pencil, and black gouache on paper

DimensionsFrame: 32 9/16 x 24 13/16 in. (82.7 x 63 cm)

Paper: 29 5/8 x 22 1/8 in. (75.2 x 56.2 cm)

Image: 22 x 17 in. (55.9 x 43.2 cm)

SignedC. Close 1979

Credit LineMuseum Purchase with funds provided by grants from the National Endowment for the Arts and R. J. Reynolds Industries, Inc.

Copyright© Chuck Close, courtesy The Pace Gallery

Object number1980.2.3.c

DescriptionBy the time Chuck Close completed his Keith/Six Drawing Series in 1979, almost a decade had elapsed since his initial manipulation of the photographic headshot on which Keith, 1970, was based. It was part of the iconic series of eight large black-and-white airbrushed heads Close made between 1968 and 1970, which included other friends: Philip Glass, Richard Serra, Nancy Graves, Frank James, Joe Zucker, and Bob Israel. Each painting was known by the sitter’s first name. They were created over many months of laborious work in the artist’s New York studio and were based on photographs taken by Close but professionally developed and printed by others according to his specifications. The massive scale of these closely cropped images, which measure nine by seven feet, magnifies every blemish and idiosyncrasy and, in Keith Hollingworth’s case, his partial facial paralysis. Over the years, Hollingworth’s photograph has been the basis for works in various media, including mezzotint in 1972, lithography, 1975, and pen and ink, 1981.The subject of Keith, is Keith Hollingworth (born 1937), a sculptor and painter, who had been an art department faculty member at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, where Close taught from 1965 to 1967. In an interview Close recalled his move to Soho: “A friend of mine at UMass … Keith Hollingworth (who’s the Keith that I painted)—came to New York at the same time. He already had a loft and he helped us find our loft. Our first loft was on Greene Street between Canal and Grant. 2000 square feet. That was $150 a month and that was considered top dollar for loft space.” [1]

In the first decade of his professional career, Close was using. almost exclusively, airbrush technology to create his works. With Keith/Mezzotint, he returned to working directly by hand and incorporated a grid. The grid system became part of his artistic investigation; his process consisted of abstract mark making, even though the final result was representational. Throughout the 1970s, the artist produced work in various media and used his signature grid format to take a small photograph and blow it up on large canvases or sheets of paper. With his 1972 print, Keith/Mezzotint, Close left his working grid visible and subsequently became very intrigued with the artistic device itself. The image itself, Keith’s face, is not a portrait, and one does not gain any insight into his personality. By making each grid square, each increment no more important than any other and simultaneously essential to and independent of the overall representational image, Close becomes an abstract artist. “I came of age in the 1960s, when minimal, reductive and process issues were certainly in the air. …That is something I was always aware of, and it interested me a great deal. I really did believe that process would set you free. Instead of having to dream up a great idea—waiting for the clouds to part and a bolt of lightning to strike your skull—you are better off just getting to work. In the process of making things, ideas will come to you.”[2]

In addition, he became extremely inventive in how he filled out his grid. “I started doing fingerprint pieces, which were an outgrowth of the dot pieces. They started out to be stamped into the spaces of the grid in the same way the dots had been sprayed into the center of each grid—left to right, top to bottom, regular marks. The fingerprint is like the dot around the mark, so then the little corners of each square were blank. So then I started to do things like cut clear plastic masks that I could put over the drawing, see through the clear plastic, see the context in which the mark was made, stamp the square fingerprint so it was like a brick that built the whole space. … Now, with the finger paintings, it was possible for everyone to see just how physical an experience it was. The physicality was very important and the personal mark. This is my actual body.” [3]

In the Keith/Six Drawing series, he repeats his black-and-white image in the same size, altering only the physical means of mark-making to either fill in grid squares or in the case of Keith/Random Fingerprint Version, eschewing the grid altogether. Yet the six images are very distinct from each other and the differences between them simply result from a variation in technique. The key to Keith/White Conté Version is the inversion of the usual relationship of black on white, which is reminiscent of Close’s notable printmaking achievement in 1972 with Keith/Mezzotint, the photograph rendered as a mezzotint engraving. With additional marks of the conté crayon, Close built up his highlights and it is the paper support itself that provides the darkest shading. Here the artist began by preparing the sheet by painting it with black gouache, then drawing in white conté crayon. Seemingly drawing in reverse to create a full range of values, the artist’s application of the conté creates the lightest shades in the composition.

The overall image is quite distinct from the others in the series, as Terri Sultan explains: “Take any small detail from the six images of Keith/Six Drawing Series, where Close represented the same ‘Keith’ at the same scale in six different techniques of analysis and transfer. The chosen detail will prove to be different in each image, not only because the medium is different but because the internal structure has shifted ever so slightly to accommodate the immediate set of graphic and tonal relationships within the local context of the sheet. Look closely, in fact, at any Close illusion. Suddenly, even in full color and continuous tone, it won’t look naïve, unaltered, or natural.” [4]

Addressing the issue of his methodology, Close explained on one occasion: “Some people wonder whether what I do is inspired by a computer and whether or not that kind of imaging is a part of what makes this work contemporary. I absolutely hate technology, and I’m computer illiterate, and I never use any laborsaving devices although I’m not convinced that a computer is a laborsaving device. I’m very much about slowing things down and making every decision myself. But, there’s no question that life in the twentieth century is about imaging. It is about photography. It is about film. And it is about new digitalized things. There are layers of similarity, I suppose, that have to do with the way computer-generated imagery is made from scanning. I scan the photograph as well, and I break it down into incremental bits, and they can break it down into incremental bits. In fact, I have a Scientific American from 1973 that I saw on a newsstand the exact day that I was walking to my first dot drawing show at Bykert Gallery. Clearly, there are some similar issues, but I had no idea that it existed. ” [5]

Reynolda House Museum of American Art acquired the Keith/Six Drawing Seriesin 1979 with funds provided by the National Endowment for the Arts, matched by R. J. Reynolds Industries, Inc. The grant stipulated that any works purchased were to be by living American artists. The museum’s Founding President, Barbara Babcock Millhouse, recalls consulting with then Whitney Museum of American Art curator Patterson Sims, who recommended that any acquisitions reflect the museum’s strength in representational art. At the time, the predominant style in this vein was Photorealism. Close was oftentimes associated with this group, but had distinguished himself by his greatly enlarged realistic images, which were built up from incremental abstract marks. Close has requested that Keith/Six Drawing Series be displayed and reproduced as a single work, which affirms it as an extended exploration of creative processes of the initial photograph. [6]

Notes:

[1] Close interview with Jud Tully, May 14–September 30, 1987, New York. Archives of American Art, http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-chuck-close-13141

[2] Terrie Sultan, Chuck Close Prints: Process and Collaboration (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press and Blaffer Gallery, the Art Museum of the University of Houston, 2003), 132.

[3] Close interview with Jud Tully, Archives of American Art.

[4] Sultan, Chuck Close Prints, 23.

[5] Close quoted in Robert Storr, Chuck Close, exhibition catalogue (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1998), 99.

[6] Object file, Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

ProvenanceFrom 1980

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC, purchased from the Pace Gallery, New York, NY on March 27, 1980 [1]

Notes:

[1] Invoice, object file.

Exhibition History1998-1999

Chuck Close

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY (2/25/1998-5/26/1998)

Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, IL (6/20/1998-9/13/1998)

Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C. (10/15/1998-1/10/1999)

Seattle Art Museum, Seattle, WA (2/18/1999-5/9/1999)

Hayward Gallery, London, England (7/22/1999-9/19/1999)

2003

Self and Soul: The Architecture of Intimacy

Asheville Art Museum at Pack Place, Asheville, NC (3/2003-5/2003)

2006

Self/Image: Portraiture from Copley to Close

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC (8/30/2006-12/30/2006)

2009

Chuck Close: The Keith Series

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC (1/17/2009-5/31/2009)

Published ReferencesChuck Close: Recent Paintings (New York: Pace Wildenstein, 1995).

Storr, Robert. Chuck Close (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2002).

Batchelder, Ann. Self and Soul: The Architecture of Intimacy (Asheville, NC: Asheville Art Museum, 2003).

Photorealism (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1980).

Status

Not on viewCollections