Skip to main contentBiographyThe Rookwood Pottery was founded in 1880 in Cincinnati, Ohio, by Maria Longworth Nichols after a year of experimentation. Mrs. Nichols was from a wealthy local family with a long-time interest in art. She had been a member of a china painting class and was inspired to create a pottery after seeing barbotine-decorated Limoges wares at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition. She acknowledged later that the pottery was "an expensive luxury" that her family could afford, but it was slow to succeed. She employed competent local ceramic workers to help during the experimental years, and in 1883 turned over management of the company to a long-time friend, William Watts Taylor.

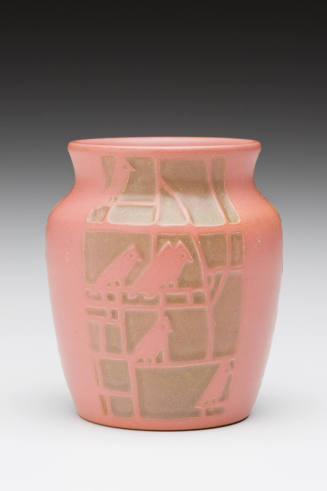

The method of decorating the earthenware shapes under the glaze with colored slips had been invented by M. Louise McLaughlin, a local rival, although the concept was based on an age-old ceramic practice of applying contrasting slip over earthenware to achieve decorative effects. Taylor reined in the experimental work of Nichols and her lady friends and created a group of standard practices that helped define Rookwood's market niche. Wares were decorated by employees who were graduates of the Cincinnati Art Academy using a limited color palette (to begin with they used browns, reds, orange and yellow under a yellow-tinted glossy glaze) with subjects of popular interest. These subjects included flowers, animals, American Indians, Old Masters, etc. This early mahogany-colored ware was referred to as Rookwood's Standard and the style suggested Old Master paintings. The ware is thoroughly marked with company logo, date of production, artist's monogram, shape number, and glaze and body types. Guides to the artists' monograms were published frequently to encourage collecting by wealthy customers. In 1889, the company became solvent. In this same year, it was awarded a Gold Medal at the Paris world's fair, placing it in the forefront of the world's potteries.

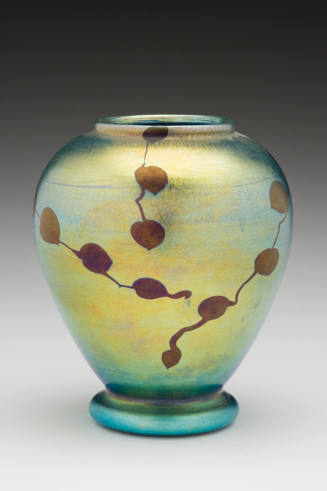

Over the years, new color palettes were developed by the artists working with the company's chemist. A matt glaze was created initially in the late 1880s, but not until 1896 were experiments resumed to create a new line. Colored matt glazes were shown at the Buffalo world's fair in 1901, and Rookwood's Vellum glaze was introduced at the St. Louis world's fair in 1904. This was a transparent matt glaze that could be used to make any underglaze colors have a matt appearance. Although the usual range of Rookwood's decorative subjects was rendered in the new glaze, landscapes were the most effective. Plaques provided the favored form because they looked so much like canvas paintings, but many vases were also painted with landscapes. The circular vase form allowed landscape design to be continuous. Instead of beginning at one side of a rectangle and ending at the other, landscapes rendered on vases drew the viewer deeper into the subject as he followed the decoration around the vase.[1]

After a decade-long struggle to remain solvent during the Depression, Rookwood finally succumbed to bankruptcy in 1941. Production continued during and after the war under several different owners. The company was finally sold in 1959 to the Herschede Hall Clock Company and production moved to Starkville, Mississippi. In 1971, Rookwood's assets were sold to Briarwood Lamps, but nothing came of the latter company's plans to develop a line of lamp bases from Rookwood's old designs.

Notes:

[1] For an in-depth discussion of this phenomenon and its relationship to American Tonalism, see Anita J. Ellis, "American Tonalism and Rookwood Pottery," in Bert Denker, ed. The Substance of Style: Perspectives on the American Arts and Crafts Movement (Winterthur, DE: Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum, 1996), pp. 301-315.

Rookwood Pottery Company

1880 - 1967

The method of decorating the earthenware shapes under the glaze with colored slips had been invented by M. Louise McLaughlin, a local rival, although the concept was based on an age-old ceramic practice of applying contrasting slip over earthenware to achieve decorative effects. Taylor reined in the experimental work of Nichols and her lady friends and created a group of standard practices that helped define Rookwood's market niche. Wares were decorated by employees who were graduates of the Cincinnati Art Academy using a limited color palette (to begin with they used browns, reds, orange and yellow under a yellow-tinted glossy glaze) with subjects of popular interest. These subjects included flowers, animals, American Indians, Old Masters, etc. This early mahogany-colored ware was referred to as Rookwood's Standard and the style suggested Old Master paintings. The ware is thoroughly marked with company logo, date of production, artist's monogram, shape number, and glaze and body types. Guides to the artists' monograms were published frequently to encourage collecting by wealthy customers. In 1889, the company became solvent. In this same year, it was awarded a Gold Medal at the Paris world's fair, placing it in the forefront of the world's potteries.

Over the years, new color palettes were developed by the artists working with the company's chemist. A matt glaze was created initially in the late 1880s, but not until 1896 were experiments resumed to create a new line. Colored matt glazes were shown at the Buffalo world's fair in 1901, and Rookwood's Vellum glaze was introduced at the St. Louis world's fair in 1904. This was a transparent matt glaze that could be used to make any underglaze colors have a matt appearance. Although the usual range of Rookwood's decorative subjects was rendered in the new glaze, landscapes were the most effective. Plaques provided the favored form because they looked so much like canvas paintings, but many vases were also painted with landscapes. The circular vase form allowed landscape design to be continuous. Instead of beginning at one side of a rectangle and ending at the other, landscapes rendered on vases drew the viewer deeper into the subject as he followed the decoration around the vase.[1]

After a decade-long struggle to remain solvent during the Depression, Rookwood finally succumbed to bankruptcy in 1941. Production continued during and after the war under several different owners. The company was finally sold in 1959 to the Herschede Hall Clock Company and production moved to Starkville, Mississippi. In 1971, Rookwood's assets were sold to Briarwood Lamps, but nothing came of the latter company's plans to develop a line of lamp bases from Rookwood's old designs.

Notes:

[1] For an in-depth discussion of this phenomenon and its relationship to American Tonalism, see Anita J. Ellis, "American Tonalism and Rookwood Pottery," in Bert Denker, ed. The Substance of Style: Perspectives on the American Arts and Crafts Movement (Winterthur, DE: Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum, 1996), pp. 301-315.

Person TypeInstitution