Skip to main content

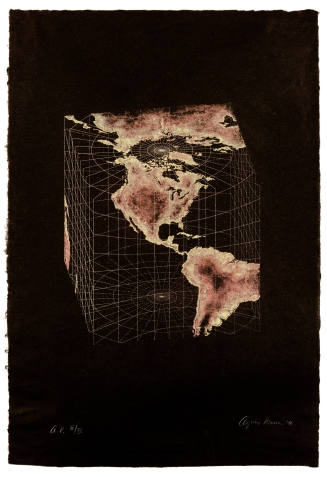

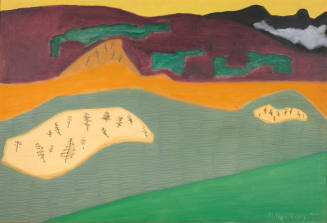

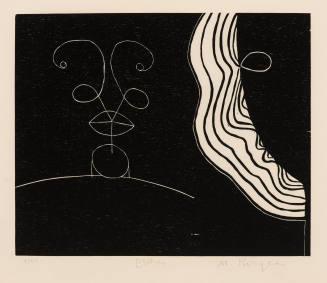

A Map of North America was printed on eight separate sheets of paper which are currently framed in four individual frames. The black and white engravings were delicately hand-colored, probably by immigrant women Tanner employed. Each of the four bears the title American Atlas across the top and is consistently bordered on two sides by a black line and a ribbon, colored pink, which contains numbers corresponding to longitude and latitude. The most fully developed section represents parts of New York and Connecticut and continues down the coast to Florida, encompassing as well the islands of Cuba, St. Domingo, Jamaica, the Bahamas and the Caribbean, as well as Central America and the northernmost part of South America. Three charts are positioned in the ocean: Comparative Altitudes of the Mountains, Towns, etc. of North America contains profiles of mountains, while the others are dedicated to “Degrees of Longitude” and “Scales of American Miles.”

The northeast quadrant is equally expansive, including the newly established state of Maine, large sections of Canada such as Newfoundland and Hudson Bay and, at the top and to the right, Greenland and Iceland. A large expanse of the Atlantic Ocean fills almost as much space as landmasses. The northwest extends as far as Asia and “Arctic Icy Ocean” and designates possessions belonging to Russia. Along the coast, sections are labeled New Hanover and New Caledonia and large inland areas are identified by Indian tribal names such as Black Foot, Knistineaux, Assinboine, and “Friendly Indians.” The area between the Rocky Mountains and the Pacific is undefined as the land was still in dispute and largely unexplored. A vertical box in the Pacific Ocean displays the western part of the Aleutian Islands.

The southwestern portion is equally divided between a map of Mexican holdings and a dual image of two eastern landmarks: Natural Bridge in Virginia and Niagara Falls in New York. These in turn are artfully divided by a large gnarled tree in which an eagle sits; shown below are a deer on the left and a beaver on the right facing the falls. Diminutive humans serve to point out the vast scale of both places. Natural Bridge and Niagara Falls were well-known sites which had been explored decades earlier, and images of them were familiar from the late eighteenth century onwards. The former was surveyed by George Washington as early as 1750 and later belonged to Thomas Jefferson. Even earlier, Father Antoine Hennepin, a French missionary, described the falls in his 1683 illustrated book, A New Discovery.

Throughout, Tanner demonstrates his concern for clarity and accuracy, which are revealed in the careful labeling and the helpful charts. Like many mapmakers of his day, he depended on previously published sources, which was true both for the map itself and the vignette of Natural Bridge and Niagara Falls. In 1825 Tanner published a text to accompany his A New American Atlas Containing Maps of the Several States of the North American Union in which he itemized his many sources, such as maps from the Lewis and Clark expedition and others by Moses Greenleaf, Zebulon Pike, and Baron von Humboldt. He acknowledges: “In the construction of the maps I have endeavoured, as far as my feeble capacity would permit, to select from the immense mass of materials collected together for the purpose, such only as were found upon actual surveys and astronomical observations; and, in the absence of these, the relations of travelers and other geographical memoranda, which appeared to be deserving of confidence, were resorted to.” He also explains his agenda: “The end proposed to be effected by the publication of the American Atlas was, to exhibit to the citizens of the United States a complete geographical view of their own country, disencumbered of that minute detail on the geography of the eastern hemisphere, which is usually introduced into our Atlasses, to the exclusion of matter more immediately interesting to those for whom they are intended.” [1]

Along with his mentor, John Melish, and other cartographers, Tanner fueled the American belief in Manifest Destiny—a term which gained wide usage in the 1840s that reflects the impetus toward western settlement. He also proved the political power of maps by addressing a contentious issue of the day: the disposition of the Oregon Territory. In 1822, Congress ordered ten copies of Tanner’s A Map of North America. Three years later, in 1825, Tanner revised the northwest boundary to reflect the fact that Russia had abandoned claims to lands below the fifty-fourth degree latitude, thus ceding the area to the United States. [2] Tanner’s reputation was further enhanced by the endorsement of the owner and editor of The North American Review, Jared Sparks, who proclaimed it a “troph[y] of American enterprise, which it becomes a discerning public to regard with favor, and reward with substantial patronage.” [3]

Notes:

[1] Henry S. Tanner, A New American Atlas Containing Maps of the Several State of the North American Union (Philadelphia, PA: 1825), 18 and 1. http://www.davidrumsey.com

[2] James V. Walker, “Henry S. Tanner and Cartographic Expression of American Expansionism in the 1820s,” Oregon Historical Quarterly 111, no 4 (Winter 2010), 5–6.

[3] Jared Sparks, “American Atlases,” The North American Review, (Boston, MA: April 1824, 390). http://digital.library.cornell.edu. A portrait of Sparks by Thomas Sully is in the collection of Reynolda House Museum of American Art.

ProvenanceThe Old Print Shop Inc., New York, NY. [1]

From 1996

Barbara B. Millhouse, New York, NY, purchased from The Old Print Shop Inc., New York, NY. [2]

Notes:

[1] Invoice from April 29, 1996.

[2] Loan Agreement.

Exhibition History2011-2012

Wonder and Enlightenment: Artist-Naturalists in the Early American South

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC (8/13/2011-2/20/2012)

(IL2003.1.34d – SE quadrant)

2017

Samuel F.B. Morse's Gallery of the Louvre and the Art of Invention

Reynolda House Museum of American Art (02/17/2017 - 06/04/2017)

Published References

DepartmentCollection of Barbara B. Millhouse

Map of North America

Artist

Henry Tanner

(1786 - 1858)

Date1822

MediumHand-colored engravings on woven paper

DimensionsOverall (approximate dimensions of each piece): 24 × 32 in. (61 × 81.3 cm)

Signed<no signature>

Credit LineCourtesy of Barbara B. Millhouse

CopyrightCopyright Unknown

Object numberIL2003.1.34a-d

DescriptionCapitalizing on the surge of interest in travel and maps, Henry S. Tanner produced A Map of North America in 1822. According to its legend it was “constructed according to the latest information.” Thus, the map shows twenty-four states along with such entities as the Arkansas and Oregon territories, while New California is depicted as part of Mexico, and Russia controls portions of the Northwest.A Map of North America was printed on eight separate sheets of paper which are currently framed in four individual frames. The black and white engravings were delicately hand-colored, probably by immigrant women Tanner employed. Each of the four bears the title American Atlas across the top and is consistently bordered on two sides by a black line and a ribbon, colored pink, which contains numbers corresponding to longitude and latitude. The most fully developed section represents parts of New York and Connecticut and continues down the coast to Florida, encompassing as well the islands of Cuba, St. Domingo, Jamaica, the Bahamas and the Caribbean, as well as Central America and the northernmost part of South America. Three charts are positioned in the ocean: Comparative Altitudes of the Mountains, Towns, etc. of North America contains profiles of mountains, while the others are dedicated to “Degrees of Longitude” and “Scales of American Miles.”

The northeast quadrant is equally expansive, including the newly established state of Maine, large sections of Canada such as Newfoundland and Hudson Bay and, at the top and to the right, Greenland and Iceland. A large expanse of the Atlantic Ocean fills almost as much space as landmasses. The northwest extends as far as Asia and “Arctic Icy Ocean” and designates possessions belonging to Russia. Along the coast, sections are labeled New Hanover and New Caledonia and large inland areas are identified by Indian tribal names such as Black Foot, Knistineaux, Assinboine, and “Friendly Indians.” The area between the Rocky Mountains and the Pacific is undefined as the land was still in dispute and largely unexplored. A vertical box in the Pacific Ocean displays the western part of the Aleutian Islands.

The southwestern portion is equally divided between a map of Mexican holdings and a dual image of two eastern landmarks: Natural Bridge in Virginia and Niagara Falls in New York. These in turn are artfully divided by a large gnarled tree in which an eagle sits; shown below are a deer on the left and a beaver on the right facing the falls. Diminutive humans serve to point out the vast scale of both places. Natural Bridge and Niagara Falls were well-known sites which had been explored decades earlier, and images of them were familiar from the late eighteenth century onwards. The former was surveyed by George Washington as early as 1750 and later belonged to Thomas Jefferson. Even earlier, Father Antoine Hennepin, a French missionary, described the falls in his 1683 illustrated book, A New Discovery.

Throughout, Tanner demonstrates his concern for clarity and accuracy, which are revealed in the careful labeling and the helpful charts. Like many mapmakers of his day, he depended on previously published sources, which was true both for the map itself and the vignette of Natural Bridge and Niagara Falls. In 1825 Tanner published a text to accompany his A New American Atlas Containing Maps of the Several States of the North American Union in which he itemized his many sources, such as maps from the Lewis and Clark expedition and others by Moses Greenleaf, Zebulon Pike, and Baron von Humboldt. He acknowledges: “In the construction of the maps I have endeavoured, as far as my feeble capacity would permit, to select from the immense mass of materials collected together for the purpose, such only as were found upon actual surveys and astronomical observations; and, in the absence of these, the relations of travelers and other geographical memoranda, which appeared to be deserving of confidence, were resorted to.” He also explains his agenda: “The end proposed to be effected by the publication of the American Atlas was, to exhibit to the citizens of the United States a complete geographical view of their own country, disencumbered of that minute detail on the geography of the eastern hemisphere, which is usually introduced into our Atlasses, to the exclusion of matter more immediately interesting to those for whom they are intended.” [1]

Along with his mentor, John Melish, and other cartographers, Tanner fueled the American belief in Manifest Destiny—a term which gained wide usage in the 1840s that reflects the impetus toward western settlement. He also proved the political power of maps by addressing a contentious issue of the day: the disposition of the Oregon Territory. In 1822, Congress ordered ten copies of Tanner’s A Map of North America. Three years later, in 1825, Tanner revised the northwest boundary to reflect the fact that Russia had abandoned claims to lands below the fifty-fourth degree latitude, thus ceding the area to the United States. [2] Tanner’s reputation was further enhanced by the endorsement of the owner and editor of The North American Review, Jared Sparks, who proclaimed it a “troph[y] of American enterprise, which it becomes a discerning public to regard with favor, and reward with substantial patronage.” [3]

Notes:

[1] Henry S. Tanner, A New American Atlas Containing Maps of the Several State of the North American Union (Philadelphia, PA: 1825), 18 and 1. http://www.davidrumsey.com

[2] James V. Walker, “Henry S. Tanner and Cartographic Expression of American Expansionism in the 1820s,” Oregon Historical Quarterly 111, no 4 (Winter 2010), 5–6.

[3] Jared Sparks, “American Atlases,” The North American Review, (Boston, MA: April 1824, 390). http://digital.library.cornell.edu. A portrait of Sparks by Thomas Sully is in the collection of Reynolda House Museum of American Art.

ProvenanceThe Old Print Shop Inc., New York, NY. [1]

From 1996

Barbara B. Millhouse, New York, NY, purchased from The Old Print Shop Inc., New York, NY. [2]

Notes:

[1] Invoice from April 29, 1996.

[2] Loan Agreement.

Exhibition History2011-2012

Wonder and Enlightenment: Artist-Naturalists in the Early American South

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC (8/13/2011-2/20/2012)

(IL2003.1.34d – SE quadrant)

2017

Samuel F.B. Morse's Gallery of the Louvre and the Art of Invention

Reynolda House Museum of American Art (02/17/2017 - 06/04/2017)

Published References

Status

Not on view