Skip to main content

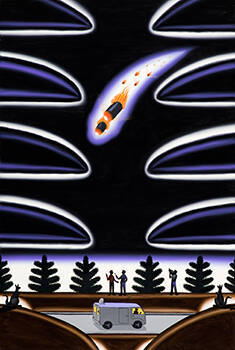

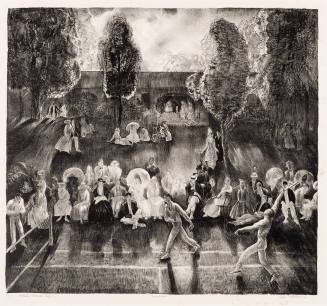

Painted on primed white canvas and without a frame, Brown’s painting Skylab by Minicam attracts attention through its strong graphic impact—seemingly devoid of any painterly virtuosity—and the narrative suggested by the presence of humans, animals, and a landscape. The scene is easily read due to its neatness and lack of ephemeral detail. [2] Brown employs repetition and symmetry in his compositions by using forms with defined contours and little modeling, a tightly controlled color palette, and spatial depth established by changes in scale and overlapping forms, using isometric rather than one-point or Renaissance perspective. His style blends the visual languages of medieval art, Surrealism, modernism, and twentieth-century folk art, and is informed by memories of his upbringing in the rural deep South.

Brown did not sign this painting, but, much like artists Andy Warhol and Georgia O’Keeffe, his style is instantly identifiable to those viewers who have seen his other work. Running from top to bottom on both sides of the vertical picture plane, cropped cloud formations establish a framing device for the scene unfolding in the center. Brown’s use of symmetry and silhouette heighten the dramatic tension, and his youthful experience in theatrical production help to explain the painting’s resemblance to a stage set as well as to an earlier series of theater paintings that Brown produced while he was still a student at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. The cloud formations are suggestive of drawn theater drapes, and the pair of kangaroos carefully placed on their hilltops to the left and right are backlit as if by footlights. Carrying the analogy further, the moment captured on stage is the demise of Skylab, the United States’s first space station, as it fell out of orbit on July 11, 1979. It disintegrated and burst into flames upon re-entering the earth’s atmosphere and landed in the general vicinity of the western Australian outback, hence the kangaroos.

Brown painted Skylab by Minicam that same year. “That the topic was so timely was no accident, for Brown has frequently drawn his imagery from common public events as they occur, and through the years familiar names like Jonestown, Skylab, [serial killer John Wayne] Gacy, Attica and Wounded Knee appear in one title after another.” [3] In Skylab by Minicam, the descending fiery fragments read as either rocket-fire or fireworks and were created by flecks of white, yellow, and orange set against a blue-black sky. In a reversal of usual artistic practice, Brown’s positive forms are rendered in dark tones and are often surrounded by white, resulting in orbs of light that suggest the darkness of outer space beyond planet earth. Appearing below is an interview in progress, where, ironically, neither the reporter nor the eyewitness are looking up at the sky. On the other hand, the cameraman and horrified woman in the news van observe the explosion. The diminutive figures are cartoon-like as well medieval-looking; Brown explained that “the ’40s styles are part of my childhood experience. Remembering my mother’s hairstyle… styles come and go, so if I were to follow fashion I’d have to change my figures every few years. I picked a style early on that had a personal meaning and simplified it.” [4] Despite the humorous aspect of kangaroos observing humans observing the media event, the painting has serious undertones. “Related to Brown’s disaster paintings of 1972–73 are Skylab by Minicam and Near Miss, both of 1979. While the former was inspired by the actual Skylab incident and the latter is a fictionalized scenario, both paintings are concerned with dramatic events beyond human control. Elements of chance and fate are evident. People can only observe the events, as evidenced by the camera crews documenting the spectacular fall of Skylab.” [5]

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) launched Skylab in November 1974 and intended it to serve as living quarters for astronauts for several weeks, as a laboratory in which they could conduct experiments in zero gravity, and as an observatory for research on the sun. One dilemma emerged: what would happen when the large space object began to be pulled out of orbit by earth’s gravity? Plans for a space shuttle that might have returned it to orbit were delayed, so by 1979 it became increasingly clear that it would fall to earth. NASA made efforts to mitigate the danger by directing it to a less populated part of the globe, although it was impossible to predict when and where it would land. As members of the public became aware of the situation, they voiced concerns about Skylab’s nuclear reactor as well as fear of severe injury or damage from falling debris. Anxiety was well founded; Skylab did not actually break up until it was about ten miles above the earth’s surface. Fortunately, most fragments probably fell into the Indian Ocean and disaster was averted. In western Australia, Stan Thornton, a seventeen year-old resident of Esperance, found several fragments of the space station and was able to collect the $10,000 reward that had been offered by the San Francisco Examiner for verifiable debris from the fallen spacecraft. [6]

For many viewers unfamiliar with the Skylab incident, Skylab by Minicam remains a compelling and mysterious image. Some of this can be attributed to Brown’s dramatic use of lights and darks, or as it is termed in art, chiaroscuro. Brown explained that in his paintings, “Light can come from anywhere; it doesn’t have to come from one source. It creates a sense of mystery. If you create something exactly like it appears, there is no mystery to it. This way you give a clue to its form, but it isn’t totally defined and it is left to the viewer to fill in the information. A certain kind of light takes it over to another dimension, like a dream world.” [7]

Notes:

[1] Barry Blinderman, “A Conversation with Roger Brown,” Arts Magazine (May 1981), 98.

[2] Timothy J. Garvey, “The Spectacle of Plains: Public Evidence, Personal Invention, and the Painting of Roger Brown,” Journal of American Studies 30, no. 2, Part 2 (August 1996), 238.

[3] Garvey, “The Spectacle of Plains,” 235.

[4] Amy Landesberg and Louise E. Shaw, Roger Brown: Selected Paintings 1973–1983, exhibition catalogue (Atlanta GA: Nexus Contemporary Art Center, University of South Florida Art Galleries, and the North Carolina Museum of Art), unpaginated, and Brown quoted in Blindermann, “A Conversation,” 99.

[5] Landesberg and Shaw, Roger Brown.

[6] Robert Bazell, “When Skylab Fell to Earth,” on The Daily Nightly/NBC news (September 23, 2011), and Skylab, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Skylab.

[7] Brown, “A Talking Profile of the Artist,” in Roger Brown, exhibition catalogue (New York: George Braziller, Inc. in association with the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, 1997), 96.

ProvenanceBarbara B. Millhouse, New York. [1]

Notes:

[1] Loan Agreement.

Exhibition History1984

Roger Brown: Selected Paintings, 1973-1983

Nexus Gallery, Atlanta, Georgia (5/3/1984-6/10/1984)

University of South Florida Art Galleries, Tampa, FL (8/3/1984-9/15/1984)

North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh, NC (9/29/1984-12/2/1984)

Published ReferencesShaw, Louise. Roger Brown: Selected Paintings, 1973-1983 (Nexus Contemporary Art Center, Atlanta, GA: 1984)

DepartmentCollection of Barbara B. Millhouse

Skylab by Minicam

Artist

Roger Brown

(1941 - 1997)

Date1979

Mediumoil on canvas

DimensionsCanvas: 72 x 48 x 1 7/8 in. (182.9 x 121.9 x 4.8 cm)

Signed<unsigned>

Credit LineCourtesy of Barbara B. Millhouse

CopyrightCourtesy of the Roger Brown Study

Collection of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago

Object numberIL2003.1.8

DescriptionDuring his relatively short career, Chicago Imagist Roger Brown developed a distinctive style and an inclination to represent contemporary events. Reflecting on his chosen subject matter, Brown opined, “I can’t say that I am consciously making a statement about conditions today. My visual interests automatically lead to that. Ultimately, ninety percent of my concerns are compositional; the formal aspect has always been more important to me. In the ‘Event’ paintings… I presented things as they happened. The comment is automatic. We all have similar reactions to a news event. Of course, mine comes out in my own style, which some people feel is like cartooning. Some people feel that you shouldn’t represent a serious subject in a cartoon style. I present everything as objectively as possible—it’s really the style that makes it look like a comment.” [1] Painted on primed white canvas and without a frame, Brown’s painting Skylab by Minicam attracts attention through its strong graphic impact—seemingly devoid of any painterly virtuosity—and the narrative suggested by the presence of humans, animals, and a landscape. The scene is easily read due to its neatness and lack of ephemeral detail. [2] Brown employs repetition and symmetry in his compositions by using forms with defined contours and little modeling, a tightly controlled color palette, and spatial depth established by changes in scale and overlapping forms, using isometric rather than one-point or Renaissance perspective. His style blends the visual languages of medieval art, Surrealism, modernism, and twentieth-century folk art, and is informed by memories of his upbringing in the rural deep South.

Brown did not sign this painting, but, much like artists Andy Warhol and Georgia O’Keeffe, his style is instantly identifiable to those viewers who have seen his other work. Running from top to bottom on both sides of the vertical picture plane, cropped cloud formations establish a framing device for the scene unfolding in the center. Brown’s use of symmetry and silhouette heighten the dramatic tension, and his youthful experience in theatrical production help to explain the painting’s resemblance to a stage set as well as to an earlier series of theater paintings that Brown produced while he was still a student at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. The cloud formations are suggestive of drawn theater drapes, and the pair of kangaroos carefully placed on their hilltops to the left and right are backlit as if by footlights. Carrying the analogy further, the moment captured on stage is the demise of Skylab, the United States’s first space station, as it fell out of orbit on July 11, 1979. It disintegrated and burst into flames upon re-entering the earth’s atmosphere and landed in the general vicinity of the western Australian outback, hence the kangaroos.

Brown painted Skylab by Minicam that same year. “That the topic was so timely was no accident, for Brown has frequently drawn his imagery from common public events as they occur, and through the years familiar names like Jonestown, Skylab, [serial killer John Wayne] Gacy, Attica and Wounded Knee appear in one title after another.” [3] In Skylab by Minicam, the descending fiery fragments read as either rocket-fire or fireworks and were created by flecks of white, yellow, and orange set against a blue-black sky. In a reversal of usual artistic practice, Brown’s positive forms are rendered in dark tones and are often surrounded by white, resulting in orbs of light that suggest the darkness of outer space beyond planet earth. Appearing below is an interview in progress, where, ironically, neither the reporter nor the eyewitness are looking up at the sky. On the other hand, the cameraman and horrified woman in the news van observe the explosion. The diminutive figures are cartoon-like as well medieval-looking; Brown explained that “the ’40s styles are part of my childhood experience. Remembering my mother’s hairstyle… styles come and go, so if I were to follow fashion I’d have to change my figures every few years. I picked a style early on that had a personal meaning and simplified it.” [4] Despite the humorous aspect of kangaroos observing humans observing the media event, the painting has serious undertones. “Related to Brown’s disaster paintings of 1972–73 are Skylab by Minicam and Near Miss, both of 1979. While the former was inspired by the actual Skylab incident and the latter is a fictionalized scenario, both paintings are concerned with dramatic events beyond human control. Elements of chance and fate are evident. People can only observe the events, as evidenced by the camera crews documenting the spectacular fall of Skylab.” [5]

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) launched Skylab in November 1974 and intended it to serve as living quarters for astronauts for several weeks, as a laboratory in which they could conduct experiments in zero gravity, and as an observatory for research on the sun. One dilemma emerged: what would happen when the large space object began to be pulled out of orbit by earth’s gravity? Plans for a space shuttle that might have returned it to orbit were delayed, so by 1979 it became increasingly clear that it would fall to earth. NASA made efforts to mitigate the danger by directing it to a less populated part of the globe, although it was impossible to predict when and where it would land. As members of the public became aware of the situation, they voiced concerns about Skylab’s nuclear reactor as well as fear of severe injury or damage from falling debris. Anxiety was well founded; Skylab did not actually break up until it was about ten miles above the earth’s surface. Fortunately, most fragments probably fell into the Indian Ocean and disaster was averted. In western Australia, Stan Thornton, a seventeen year-old resident of Esperance, found several fragments of the space station and was able to collect the $10,000 reward that had been offered by the San Francisco Examiner for verifiable debris from the fallen spacecraft. [6]

For many viewers unfamiliar with the Skylab incident, Skylab by Minicam remains a compelling and mysterious image. Some of this can be attributed to Brown’s dramatic use of lights and darks, or as it is termed in art, chiaroscuro. Brown explained that in his paintings, “Light can come from anywhere; it doesn’t have to come from one source. It creates a sense of mystery. If you create something exactly like it appears, there is no mystery to it. This way you give a clue to its form, but it isn’t totally defined and it is left to the viewer to fill in the information. A certain kind of light takes it over to another dimension, like a dream world.” [7]

Notes:

[1] Barry Blinderman, “A Conversation with Roger Brown,” Arts Magazine (May 1981), 98.

[2] Timothy J. Garvey, “The Spectacle of Plains: Public Evidence, Personal Invention, and the Painting of Roger Brown,” Journal of American Studies 30, no. 2, Part 2 (August 1996), 238.

[3] Garvey, “The Spectacle of Plains,” 235.

[4] Amy Landesberg and Louise E. Shaw, Roger Brown: Selected Paintings 1973–1983, exhibition catalogue (Atlanta GA: Nexus Contemporary Art Center, University of South Florida Art Galleries, and the North Carolina Museum of Art), unpaginated, and Brown quoted in Blindermann, “A Conversation,” 99.

[5] Landesberg and Shaw, Roger Brown.

[6] Robert Bazell, “When Skylab Fell to Earth,” on The Daily Nightly/NBC news (September 23, 2011), and Skylab, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Skylab.

[7] Brown, “A Talking Profile of the Artist,” in Roger Brown, exhibition catalogue (New York: George Braziller, Inc. in association with the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, 1997), 96.

ProvenanceBarbara B. Millhouse, New York. [1]

Notes:

[1] Loan Agreement.

Exhibition History1984

Roger Brown: Selected Paintings, 1973-1983

Nexus Gallery, Atlanta, Georgia (5/3/1984-6/10/1984)

University of South Florida Art Galleries, Tampa, FL (8/3/1984-9/15/1984)

North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh, NC (9/29/1984-12/2/1984)

Published ReferencesShaw, Louise. Roger Brown: Selected Paintings, 1973-1983 (Nexus Contemporary Art Center, Atlanta, GA: 1984)

Status

Not on view