Skip to main content

The left hand referenced in the title has been severed and placed centrally in a large, ovoid form that suggests a bird’s nest. Although by implication the severed limb is a left or “sinister” hand made by the artist’s handprint, it is painted in glowing yellow in the tradition of the right, or sanctified hand. Directly above each fingertip and the thumb are barely legible santos: presumably the Madonna, the Christ Child, and the three kings from the nativity story. In Puerto Rican tradition, the hand-carved wooden santos, or sacred figurines of the household, are often freshened up with paint whenever the house is painted, and as a result they acquire a particular patina from the repeated process. Adherents to the faith pray to their santos for healing. The linoleum floor and the charred supports allude to the family home in San Juan. The figure of Arnaldo is oversized for the dwelling, hinting that perhaps home/Puerto Rico is too small and constraining for the artist’s survival. Another overt reference to Puerto Rico is the printed impression of a lace tablecloth, a cottage industry of the Commonwealth. [2] Roche has explained “being Puerto Rican is exactly that: to live a dichotomy with our political and cultural reality. Fortunately, we do not have a dictatorship, nor are we governed by a military junta. Our political situation opens up endless possibilities and opportunities for us. I form part of a Caribbean and Latin reality in the United States. … I can assure you that I am extremely proud of my people and of my country.”[3]

Curator Thomas Denenberg wrote of this incredible painting “Often overlooked, religion permeates the work of Roche. [Professor] Francisco Cabanillas has noted a tension between a Catholic sense of institutionalized religion (order and history), the Protestant sense of self, and a sub-conscious manifestation of Santeria in the artist’s work. The Black Man Always Hides His Left Hand is an archetype for the study of this intersection. The left hand, with its sinister biblical and vernacular associations, is here cut off by the black man and placed in a nest-like form that takes the place of his heart.” [4]

Roche’s process of painting his large canvasses is quite complicated. He begins by applying several layers of oil paint in a prismatic sequence over a stretched canvas surface, which he then removes from the stretchers in order to wrap around his model or an object. The figure or form is completely enveloped, so Roche cannot rely on what he sees but must intuit the position of the model as he scratches through the paint layers to establish an outline on the surface. Then he re-stretches the canvas. He will then continue by painting or printing and re-working the entire surface. He repeats the process as he deems necessary, sometimes as many as five times. The black surface paint is scratched through to reveal the rich colors underneath, as in scratch-art drawings. “I could not tell you whether part of my conscious or unconscious comes to life in these processes. I think of the idea for a work for months beforehand, it is the physical act of painting that the action of my work ratifies the urgency of my ideas, connecting all the actual elements I rub, print or project on the canvas. That is when the subconscious is released, materializing itself through digging, pasting, and tracing.” [5]

In speaking of his psychic pain, Roche has described his objective: “the intention was not to heal the wound, but to touch it … wounds of that kind are never healed, and the act of making public what had not been openly expressed is extremely painful. To re-establish links with a deceased loved one became a necessity.” [6] Roche feels that the physical act of scratching through the black to the yellow and red is reminiscent of his sister’s wounds and dried blood on her skin yet also a transformative act of restoring life and color from darkness.

Notes:

[1] Mercedes Lizcano, Interview with Arnaldo Roche-Rabell January 12, 2005 http://www.latinart.com/transcript.cfm?id=67

[2] Hobbs, Robert Carleton, Arnaldo Roche-Rabell: The Uncommonwealth (Seattle WA: University of Washington Press, 1996), 18–19.

[3] Lizcano, Interview.

[4] Denenberg to the Collection Committee, Board of Directors of Reynolda House Museum of American Art, December 2, 2005, and updated May 3, 2006.

[5] Lizcano, Interview.

[6] Lizcano, Interview.

ProvenanceBefore 2006

Robert Hobbs. [1]

From 2006

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC, given by Robert Hobbs. [2]

Notes:

[1] See Note 1.

[2] Deed of Gift. See Object File.

Exhibition History1999

Saints, Sinners and Sacrifices - Religious Imagery in Contemporary Latin American Art

George Adams Gallery, New York, NY (11/19/1999-12/24/1999)

2008

New World Views: Gifts from Jean Crutchfield and Robert Hobbs

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC (5/20/2008-8/31/2008)

2014-2015

Love & Loss

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC (10/11/2014-12/13/2015)

2021

The Voyage of Life: Art, Allegory, and Community Response

Reynolda House Museum of American Art (7/16/2021 - 12/12/2021)

Published ReferencesReynolda House Museum of American Art, Reynolda: Her Muses, Her Stories , with contributions by Martha R. Severens and David Park Curry (Winston-Salem, N.C.: Reynolda House Museum of American Art affiliated with Wake Forest University, 2017). pg 244, 245

DepartmentAmerican Art

The Black Man Always Hides His Left Hand

Artist

Arnaldo Roche

(American, 1955 - 2018)

Date1993

Mediumoil on canvas

DimensionsCanvas: 74 1/4 x 78 1/8 in. (188.6 x 198.4 cm)

Signed1993 Arnaldo Roche-Rabell

Credit LineGift of Jean Crutchfield and Robert Hobbs in honor of Barbara Babcock Millhouse and Nik Millhouse

Copyright© Arnaldo Roche-Rabell. Courtesy of the Artist and Walter Otero Contemporary Art

Object number2005.5.1

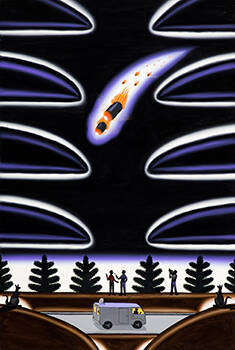

DescriptionArnaldo Roche explains that he “live[s] intensely in search of the physical and psychological life of others. In this world created on canvas everything must leave its mark.” [1] The Black Man Always Hides His Left Hand vividly demonstrates this point of view. According to art historian Robert Hobbs, the painting references a family tragedy involving the artist’s brilliant older brother Felix, who shot their sister Nancy while Arnaldo, fourteen at the time, watched helplessly in horror. The family did not understand what was happening to Felix, a brilliant student-athlete, but also intermittently schizophrenic. As a result, an atmosphere of grief, anger, and fear was prevalent in the home. Arnaldo remembers his brother coming to the bed they shared in the family’s modest home with a knife. The features of the oversize head in the composition belong to the artist, replacing those of his brother Felix. While Arnaldo was studying at the Art Institute of Chicago, he learned that Felix had wandered away as he was prone to do and was later found dead. The left hand referenced in the title has been severed and placed centrally in a large, ovoid form that suggests a bird’s nest. Although by implication the severed limb is a left or “sinister” hand made by the artist’s handprint, it is painted in glowing yellow in the tradition of the right, or sanctified hand. Directly above each fingertip and the thumb are barely legible santos: presumably the Madonna, the Christ Child, and the three kings from the nativity story. In Puerto Rican tradition, the hand-carved wooden santos, or sacred figurines of the household, are often freshened up with paint whenever the house is painted, and as a result they acquire a particular patina from the repeated process. Adherents to the faith pray to their santos for healing. The linoleum floor and the charred supports allude to the family home in San Juan. The figure of Arnaldo is oversized for the dwelling, hinting that perhaps home/Puerto Rico is too small and constraining for the artist’s survival. Another overt reference to Puerto Rico is the printed impression of a lace tablecloth, a cottage industry of the Commonwealth. [2] Roche has explained “being Puerto Rican is exactly that: to live a dichotomy with our political and cultural reality. Fortunately, we do not have a dictatorship, nor are we governed by a military junta. Our political situation opens up endless possibilities and opportunities for us. I form part of a Caribbean and Latin reality in the United States. … I can assure you that I am extremely proud of my people and of my country.”[3]

Curator Thomas Denenberg wrote of this incredible painting “Often overlooked, religion permeates the work of Roche. [Professor] Francisco Cabanillas has noted a tension between a Catholic sense of institutionalized religion (order and history), the Protestant sense of self, and a sub-conscious manifestation of Santeria in the artist’s work. The Black Man Always Hides His Left Hand is an archetype for the study of this intersection. The left hand, with its sinister biblical and vernacular associations, is here cut off by the black man and placed in a nest-like form that takes the place of his heart.” [4]

Roche’s process of painting his large canvasses is quite complicated. He begins by applying several layers of oil paint in a prismatic sequence over a stretched canvas surface, which he then removes from the stretchers in order to wrap around his model or an object. The figure or form is completely enveloped, so Roche cannot rely on what he sees but must intuit the position of the model as he scratches through the paint layers to establish an outline on the surface. Then he re-stretches the canvas. He will then continue by painting or printing and re-working the entire surface. He repeats the process as he deems necessary, sometimes as many as five times. The black surface paint is scratched through to reveal the rich colors underneath, as in scratch-art drawings. “I could not tell you whether part of my conscious or unconscious comes to life in these processes. I think of the idea for a work for months beforehand, it is the physical act of painting that the action of my work ratifies the urgency of my ideas, connecting all the actual elements I rub, print or project on the canvas. That is when the subconscious is released, materializing itself through digging, pasting, and tracing.” [5]

In speaking of his psychic pain, Roche has described his objective: “the intention was not to heal the wound, but to touch it … wounds of that kind are never healed, and the act of making public what had not been openly expressed is extremely painful. To re-establish links with a deceased loved one became a necessity.” [6] Roche feels that the physical act of scratching through the black to the yellow and red is reminiscent of his sister’s wounds and dried blood on her skin yet also a transformative act of restoring life and color from darkness.

Notes:

[1] Mercedes Lizcano, Interview with Arnaldo Roche-Rabell January 12, 2005 http://www.latinart.com/transcript.cfm?id=67

[2] Hobbs, Robert Carleton, Arnaldo Roche-Rabell: The Uncommonwealth (Seattle WA: University of Washington Press, 1996), 18–19.

[3] Lizcano, Interview.

[4] Denenberg to the Collection Committee, Board of Directors of Reynolda House Museum of American Art, December 2, 2005, and updated May 3, 2006.

[5] Lizcano, Interview.

[6] Lizcano, Interview.

ProvenanceBefore 2006

Robert Hobbs. [1]

From 2006

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC, given by Robert Hobbs. [2]

Notes:

[1] See Note 1.

[2] Deed of Gift. See Object File.

Exhibition History1999

Saints, Sinners and Sacrifices - Religious Imagery in Contemporary Latin American Art

George Adams Gallery, New York, NY (11/19/1999-12/24/1999)

2008

New World Views: Gifts from Jean Crutchfield and Robert Hobbs

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC (5/20/2008-8/31/2008)

2014-2015

Love & Loss

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC (10/11/2014-12/13/2015)

2021

The Voyage of Life: Art, Allegory, and Community Response

Reynolda House Museum of American Art (7/16/2021 - 12/12/2021)

Published ReferencesReynolda House Museum of American Art, Reynolda: Her Muses, Her Stories , with contributions by Martha R. Severens and David Park Curry (Winston-Salem, N.C.: Reynolda House Museum of American Art affiliated with Wake Forest University, 2017). pg 244, 245

Status

Not on view