Nam June Paik

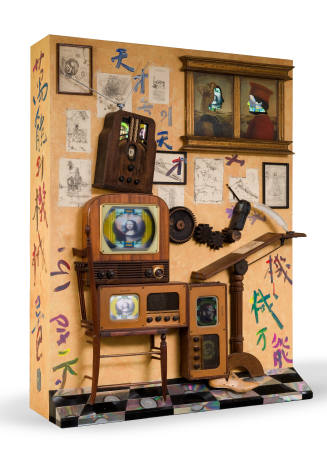

A major international artist whose forward-thinking work anticipated and encouraged developments in contemporary art and social media, the Korean-American Nam June Paik (1932–2006) created memorable works of performance and installation art using electronic media as his tools. Initially, he worked with musical instruments, then added live television feeds, videotape, synthesizers, robotics, broadcast, and digital media. “As in a collage, Paik combines into an homogeneous whole the sensitivity of a musician and artist and the intelligence and rationality of a scientist; an anarchist’s implacable desire to shock and the gentle smile of sage; a knowledge of technical possibilities and a rejection of what seems the most obvious fundamentals of technology.”[1]

Paik described himself as “a poor artist from a poor country,” [2] but in reality he was born the third son of a textile manufacturer—the family firm was the Taechang Textile Company—in Seoul, Korea. At the time, Korea was under Japanese rule. The artist’s family was able to give him an excellent education and supported him well into his thirties. Paik began studying classical piano when he was fourteen years old and, within a year, his high school composition teachers introduced him to the music of Arnold Schönberg, the Viennese composer who invented a method of musical composition called atonality using a twelve-note tone scale. Because of the Korean War, in 1950 the Paik family immigrated briefly to Hong Kong and then settled in Kamakura, Japan, although the artist’s father remained in Korea during the war because his firm also ran a shipping line. Paik graduated from the University of Tokyo in 1956, where he studied art history, musicology, and philosophy. Significantly, his thesis was on Schönberg. Paik continued these areas of studies as a student at Ludwig Maximilians University in Munich, Germany, during1956–1957. There, an encounter with the German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen led him to study composition at the Staatliche Hochschule für Musik in Freiburg.

In 1958, Paik met the American avant-garde composer John Cage at the Darmstadt International Summer Course for New Music. After attending Cage’s concert, Paik emerged as a proponent of action music. Through Cage he would indirectly meet his other great collaborator and friend, the German sculptor Joseph Beuys who had attended the 1959 debut performance of Paik’s Hommage à John Cage at Galerie 22 in Düsseldorf. Paik’s piece featured playing impromptu and random sounds on a piano and three tape recorders, throwing an egg, activating noisy toys, overturning a piano, singing, and yelling. Beuys became a spontaneous partner of Paik in 1963 when, using an axe, he smashed one of four pianos in Paik’s one-man exhibition, Exposition of Music—Electronic Television, held at the Galerie Parnass in Wuppertal, an exhibition notable for being the first to include television monitors. By that time Paik was an active participant of the Fluxus group, an international neo-Dadaist cultural movement that shared the theatricality of art happenings, but was anti-expressionist and anti-sentiment. Paik met Fluxus co-founder George Maciunas in 1962, who, along with Paik and Wolf Vostell, was profoundly influenced by the ideas of both Cage and Marcel Duchamp. Members of the group favored minimalism in the “events” they staged, allowing for chance and audience participation. Paik and Beuys are considered the most famous artists of Fluxus, which included, among others, Yoko Ono, Christo, Terry Riley, Jonas Mekas, and Carolee Schneemann. The short-lived movement, if it was one, proved highly influential on subsequent developments in the arts.

After a return visit to Japan, where he met Shuya Abe, with whom he would later collaborate and develop a video synthesizer, Paik moved in 1964 to New York. He began working with Charlotte Moorman, a classically trained cellist who was already performing groundbreaking music by Cage and others. Her collaboration with Paik would produce notable—and notorious—performances including Human Cello, 1965, Opera Sextronique, 1967, for which they both were arrested, and TV Bra, 1969. For the latter, Moorman performed nearly in the nude with Paik videotaping her cello performance with a live feed to the two small television monitors that covered her breasts. These daring and innovative works reflect their era and are considered important to subsequent developments in video, performance, and feminist art.

In 1965, Paik had his first one-man exhibition in the United States at the Galeria Bonino in New York City and created Magnet TV. He also purchased Sony’s first portable video recorder for the consumer market, promptly started filming, and then premiered the videotape that evening at the Café à Go-Go. With Shuya Abe, he invented a video analog synthesizer, a mechanical device that electronically creates and/or electronically manipulates visual material—with or without a camera feed. The imagery can then be displayed or projected on all types of video equipment such as TV and computer monitors, or projectors. He built one for WGBH in Boston in 1969 and, two years later, one for the WNET TV lab in New York.

The artist continued to exhibit in the United States and overseas; he had his first retrospective in 1976 at the Kolnisher Kunstverein in Cologne and one at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1982. Considered the founder of video art, some of his most popular images incorporate both insight and humor, as in the variations of Buddha statues contemplating themselves on a live feed monitor. Inspired by George Orwell’s novel 1984, Paik organized a worldwide telethon of satellite-linked television studios in New York, West Germany, South Korea, and Paris with an audience of twenty-five million people. With both live and pre-recorded material, participants included such avant-garde artists and musicians as Cage, Merce Cunningham, Laurie Anderson, and pop artists like The Thompson Twins. Other notable projects included the 1003-monitor tower, The More the Better, for the 1988 Seoul Olympic Games, and his work, along with Hans Haake, for the German Pavilion of the 1993 Venice Biennale which featured his large-scale assemblage Electronic Superhighway.

Paik accepted a teaching and chairmanship position at the Staatliche Kunstakademie in Düsseldorf in 1979, which he held until a stroke caused him to resign in 1996. Never fully recovered and confined to a wheelchair, he oversaw The Worlds of Nam June Paik at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in 2000, and received a Lifetime Achievement in Contemporary Sculpture Award bestowed by the International Sculpture Center in 2001. In 2004, Nam June Paik: Global Groove was held at Deutsche Guggenheim in Berlin. Paik died in Miami, Florida, in 2006, at the age of seventy-four.

In sum, “this form of intellectual and spiritual entanglement, culled from Cage and the lessons of the Dadaists, has provided the matrix for Paik’s videotape work. Within this matrix he has been able to address a range of concerns that surface and resurface, including the paradoxes of time perceived and time understood from both the linear and Western perspective and the non-linear Eastern one, the hegemony of European academicism in art and music, and of course the role of the revolution in communications and control (cybernetics) in the transformation of global consciousness.” [3] It is logical to think of Paik, who in 1974 ostensibly predicted the development of the Internet when he coined the term “electronic superhighway,” in connection with the global impact of social media, from banal YouTube videos featuring cats to the political upheaval of the 2011 Arab Spring.

Notes:

[1] Wolf Herzogenrath, “The anti-technological technology of Nam June Paik’s Robots,” in Nam June Paik: Video Works 1963–68, exhibition catalogue (London: Hayward Gallery, 1988), 6.

[2] Alex Graham, “Nam June Paik,” in Nam June Paik: Video Works 1963-88, exhibition catalogue (London: Hayward Gallery, 1988), 34.

[3] John G. Hanhardt, “Paik’s Video Sculpture,” in Nam June Paik, exhibition catalogue (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art in association with W. W. Norton & Company, 1982), 102.