Skip to main content

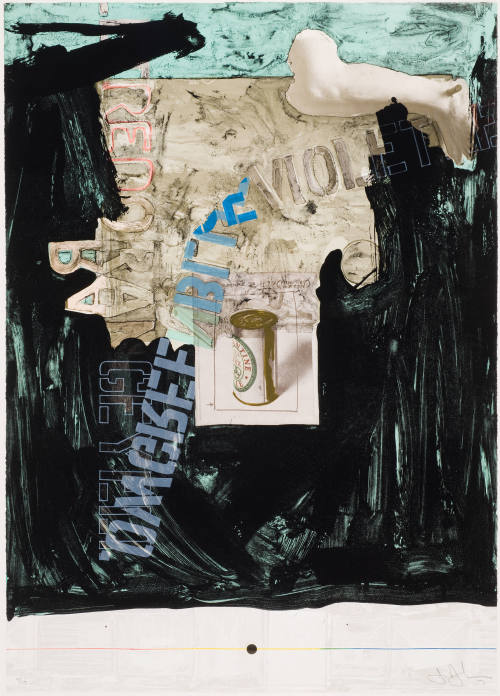

Decoy is a large format, somewhat somber, print that unites large sections of black broadly brushed on both sides and across the bottom. The upper middle section is a similarly treated passage in tan, with a turquoise-green band across the top that balances a register at the very bottom. Winding its way from upper to lower left and then diagonally to upper right is a ribbon of stencil letters that spells out colors: red/orange/yellow/green/blue/violet, and re, the beginning of another red. Some of the letters have mirror images and some bear the colors they spell. Below, a thin line of color from red to violet—the color spectrum—reiterates the stenciled words. Blocked out in squares in the lower frieze are emblems derived from earlier works by Johns: a flag, a flashlight, a Savarin can with brushes, superimposed numerals, and a light bulb. Each one has a large X, a cancellation mark used by printmakers indicating that the series is finished. At the very middle is a round hole perforating the paper. Virtually at the center of the composition is a Ballantine ale can in a kind of window that punctures the picture plane. The most mysterious element of all is the photograph of a cast of two lower legs in the upper right.

The creation of Decoy was a milestone in Johns’s oeuvre: it was the first time he used the offset printing press at Universal Limited Art Editions. This allowed photographic images of the ale can and the cast, for example, to be laid directly on the plates without reversing them. These crisp graphic images—reminiscent of those used by some of the Pop artists—sit in strong contrast to the heavy, dark swaths of pigment that recall the work of Willem de Kooning, who is associated with the ale cans. In a television interview Johns explained their origin, and then laughed: “It occurs to me that you are talking about my beer cans, which have a story behind them. I was doing at that time sculptures of small objects—flashlights and light bulbs. Then I heard a story about Willem de Kooning. He was annoyed with my dealer, Leo Castelli, for some reason, and said something like, ‘That son of a bitch, you could give him two beer cans and he could sell them.’ I heard this and thought, ‘What a sculpture—two beer cans.’ It seemed to fit in perfectly with what I was doing, so I did them—and Leo sold them.” [2]

From his earliest work, Johns was interested in color: how one relates to another, how one color is perceived differently depending on what color is contiguous, and who is viewing it. He also liked that numerals stand for abstract concepts and the way words relate to objects: “I thought that one thing to do with the written word was to pretend it was an object that could be bent, turned upside-down, and I began more or less folding words, or painting the illusion of a folded word, I guess that’s what you say. Then once you fold the word you get the part of it in reverse.” [3] The idea of reversal, of course, is germane to printmaking, where the artist has to conceive backwards, unless he is implementing photographic images on an offset press as Johns did in Decoy .

Compositionally, the two photographically reproduced elements, the ale can and the cast, vie for attention. The former are clear and familiar, while the legs are bizarre in their derivation and their placement. Eager to expand his repertoire, Johns had translated some of his motifs into sculpture, sometimes as three-dimensional objects and at other times attached directly to canvases, much as his close friend Robert Rauschenberg had done in his series of “combines.” These mixed-media collages and assemblages used ordinary, concrete objects and blurred the line between representation and reality.

Johns’s first casts of body parts date to 1954, and his most famous assemblage using casts came a year later in Target with Plaster Casts, an encaustic with a frieze above it consisting of compartments holding nine different body parts. In his typically laconic fashion, Johns explained the inspiration for the piece, “My studio had in it various plaster casts that I had done for people: hands and feet and faces and things. So I simply thought of these wooden sections… as being able to lift up and see something… and I decided to put them in it. So I did.” [4] Later, Johns made plaster casts of a friend’s lower extremity sitting in a simple kitchen chair and featured it in several works from the sixties.

Unlike many of Johns’s lithographs, Decoy was conceived first as a print, then developed later into oil paintings, one the same size, the second even larger. He also did a second lithograph. This methodology is not unusual for Johns, who often spoke of needing to fully exhaust an idea. He struggled with some images, such as his iconic flag, for over half a century. In an interview he explained, “The paintings and prints are two different situations. … Primarily, it’s the printmaking techniques that interest me. My impulse to make prints has nothing to do with my thinking it’s a good way to express myself. It’s more a means to experiment in the technique. What interests me is the technical innovation possible for me in printmaking.” [5] With its use of the offset lithograph press at Universal Limited Art Editions, Decoy was a seminal work in Johns’s pursuit of “technical innovation.”

Notes:

[1] Johns, quoted in David Sylvester, "What the Pundits Say About Jasper Johns," Television script. BBC Channel VT4, recorded January 20, 1965, reprinted in Kirk Varnedoe, ed. Jasper Johns: Writings, Sketchbook Notes, Interviews (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1996), 113.

[2] Johns, quoted in Gene Swenson, “What is Pop Art? Part II,” Artnews 62, no.10 (February 1964), 43, 66–67, reprinted in Varnedoe, ed. Jasper Johns: Writings, 92.

[3] Johns, quoted in USA Artists 8: Jasper Johns, 1966, 30-minute, 16 mm. Black and white. Produced and directed by Lane Slate, written by Alan R. Solomon, narrated by Norman Rose. TV documentary produced by NET (National Educational Network) and Radio Center, reprinted in Varnedoe, ed. Jasper Johns: Writings, 123.

[4] Johns, quoted in Carol Mancusi-Ungaro, “A Sum of Corrrections,” in Jeffrey Weiss, Jasper Johns: An Allegory of Painting, 1955–1965 (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2007), 241.

[5] Johns, quoted in Joseph E. Young, "Jasper Johns: An Appraisal," Art International (Lugano) 13, no. 7 (September 1969), 50–56. Interview conducted in Los Angeles, January 24, 1969, reprinted in Varnedoe, ed. Jasper Johns: Writings, 130.

ProvenanceTo 1983

Barbara B. Millhouse, New York, NY and Winston-Salem, NC. [1]

From 1983

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC, given by Barbara B. Millhouse on December 29, 1983. [2]

Notes:

[1] Deed of Gift, object file.

[2] See note 1.

Exhibition History1976

Twentieth Century American Print Collection

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC (12/3/1976)

2007

Abstract/Object

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC (2/27/2007-6/17/2007)

2022

Substrata: The Spirit of Collage in 76 Years of Art

Reynolda House Musuem of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC (3/18/2022-7/31/22)

Published ReferencesReynolda House Museum of American Art, Reynolda: Her Muses, Her Stories , with contributions by Martha R. Severens and David Park Curry (Winston-Salem, N.C.: Reynolda House Museum of American Art affiliated with Wake Forest University, 2017). pg. 186, 187

DepartmentAmerican Art

Decoy

Artist

Jasper Johns

(born 1930)

Date1971

Mediumlithograph from one stone, hand-printed, and eighteen plates

DimensionsFrame: 51 1/4 x 39 1/4 in. (130.2 x 99.7 cm)

Image: 41 1/2 x 29 1/2 in. (105.4 x 74.9 cm)

SignedJ. Johns '71

Credit LineGift of Barbara B. Millhouse

Copyright© 2021 Jasper Johns and ULAE / Licensed by VAGA at Artist Rights Society (ARS), NY, Published by Univeral Limited Art Editions

Object number1983.2.12

DescriptionMuch of Jasper Johns’s work consists of a delicate balance between the mundane and the sophisticated. His predilection for stencil letters and simple words belies the inscrutable combination of disparate elements, some recognizable, some not. The totality is open to interpretation, as Johns has typically been reluctant to divulge the meaning of his art. “I feel that works of art are an opportunity for people to construct meaning, so I don’t usually tell what they mean. It conveys to people that they have to participate. They either have to pay a great deal of attention or dismiss it.” [1]Decoy is a large format, somewhat somber, print that unites large sections of black broadly brushed on both sides and across the bottom. The upper middle section is a similarly treated passage in tan, with a turquoise-green band across the top that balances a register at the very bottom. Winding its way from upper to lower left and then diagonally to upper right is a ribbon of stencil letters that spells out colors: red/orange/yellow/green/blue/violet, and re, the beginning of another red. Some of the letters have mirror images and some bear the colors they spell. Below, a thin line of color from red to violet—the color spectrum—reiterates the stenciled words. Blocked out in squares in the lower frieze are emblems derived from earlier works by Johns: a flag, a flashlight, a Savarin can with brushes, superimposed numerals, and a light bulb. Each one has a large X, a cancellation mark used by printmakers indicating that the series is finished. At the very middle is a round hole perforating the paper. Virtually at the center of the composition is a Ballantine ale can in a kind of window that punctures the picture plane. The most mysterious element of all is the photograph of a cast of two lower legs in the upper right.

The creation of Decoy was a milestone in Johns’s oeuvre: it was the first time he used the offset printing press at Universal Limited Art Editions. This allowed photographic images of the ale can and the cast, for example, to be laid directly on the plates without reversing them. These crisp graphic images—reminiscent of those used by some of the Pop artists—sit in strong contrast to the heavy, dark swaths of pigment that recall the work of Willem de Kooning, who is associated with the ale cans. In a television interview Johns explained their origin, and then laughed: “It occurs to me that you are talking about my beer cans, which have a story behind them. I was doing at that time sculptures of small objects—flashlights and light bulbs. Then I heard a story about Willem de Kooning. He was annoyed with my dealer, Leo Castelli, for some reason, and said something like, ‘That son of a bitch, you could give him two beer cans and he could sell them.’ I heard this and thought, ‘What a sculpture—two beer cans.’ It seemed to fit in perfectly with what I was doing, so I did them—and Leo sold them.” [2]

From his earliest work, Johns was interested in color: how one relates to another, how one color is perceived differently depending on what color is contiguous, and who is viewing it. He also liked that numerals stand for abstract concepts and the way words relate to objects: “I thought that one thing to do with the written word was to pretend it was an object that could be bent, turned upside-down, and I began more or less folding words, or painting the illusion of a folded word, I guess that’s what you say. Then once you fold the word you get the part of it in reverse.” [3] The idea of reversal, of course, is germane to printmaking, where the artist has to conceive backwards, unless he is implementing photographic images on an offset press as Johns did in Decoy .

Compositionally, the two photographically reproduced elements, the ale can and the cast, vie for attention. The former are clear and familiar, while the legs are bizarre in their derivation and their placement. Eager to expand his repertoire, Johns had translated some of his motifs into sculpture, sometimes as three-dimensional objects and at other times attached directly to canvases, much as his close friend Robert Rauschenberg had done in his series of “combines.” These mixed-media collages and assemblages used ordinary, concrete objects and blurred the line between representation and reality.

Johns’s first casts of body parts date to 1954, and his most famous assemblage using casts came a year later in Target with Plaster Casts, an encaustic with a frieze above it consisting of compartments holding nine different body parts. In his typically laconic fashion, Johns explained the inspiration for the piece, “My studio had in it various plaster casts that I had done for people: hands and feet and faces and things. So I simply thought of these wooden sections… as being able to lift up and see something… and I decided to put them in it. So I did.” [4] Later, Johns made plaster casts of a friend’s lower extremity sitting in a simple kitchen chair and featured it in several works from the sixties.

Unlike many of Johns’s lithographs, Decoy was conceived first as a print, then developed later into oil paintings, one the same size, the second even larger. He also did a second lithograph. This methodology is not unusual for Johns, who often spoke of needing to fully exhaust an idea. He struggled with some images, such as his iconic flag, for over half a century. In an interview he explained, “The paintings and prints are two different situations. … Primarily, it’s the printmaking techniques that interest me. My impulse to make prints has nothing to do with my thinking it’s a good way to express myself. It’s more a means to experiment in the technique. What interests me is the technical innovation possible for me in printmaking.” [5] With its use of the offset lithograph press at Universal Limited Art Editions, Decoy was a seminal work in Johns’s pursuit of “technical innovation.”

Notes:

[1] Johns, quoted in David Sylvester, "What the Pundits Say About Jasper Johns," Television script. BBC Channel VT4, recorded January 20, 1965, reprinted in Kirk Varnedoe, ed. Jasper Johns: Writings, Sketchbook Notes, Interviews (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1996), 113.

[2] Johns, quoted in Gene Swenson, “What is Pop Art? Part II,” Artnews 62, no.10 (February 1964), 43, 66–67, reprinted in Varnedoe, ed. Jasper Johns: Writings, 92.

[3] Johns, quoted in USA Artists 8: Jasper Johns, 1966, 30-minute, 16 mm. Black and white. Produced and directed by Lane Slate, written by Alan R. Solomon, narrated by Norman Rose. TV documentary produced by NET (National Educational Network) and Radio Center, reprinted in Varnedoe, ed. Jasper Johns: Writings, 123.

[4] Johns, quoted in Carol Mancusi-Ungaro, “A Sum of Corrrections,” in Jeffrey Weiss, Jasper Johns: An Allegory of Painting, 1955–1965 (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2007), 241.

[5] Johns, quoted in Joseph E. Young, "Jasper Johns: An Appraisal," Art International (Lugano) 13, no. 7 (September 1969), 50–56. Interview conducted in Los Angeles, January 24, 1969, reprinted in Varnedoe, ed. Jasper Johns: Writings, 130.

ProvenanceTo 1983

Barbara B. Millhouse, New York, NY and Winston-Salem, NC. [1]

From 1983

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC, given by Barbara B. Millhouse on December 29, 1983. [2]

Notes:

[1] Deed of Gift, object file.

[2] See note 1.

Exhibition History1976

Twentieth Century American Print Collection

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC (12/3/1976)

2007

Abstract/Object

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC (2/27/2007-6/17/2007)

2022

Substrata: The Spirit of Collage in 76 Years of Art

Reynolda House Musuem of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC (3/18/2022-7/31/22)

Published ReferencesReynolda House Museum of American Art, Reynolda: Her Muses, Her Stories , with contributions by Martha R. Severens and David Park Curry (Winston-Salem, N.C.: Reynolda House Museum of American Art affiliated with Wake Forest University, 2017). pg. 186, 187

Status

Not on view