Skip to main content

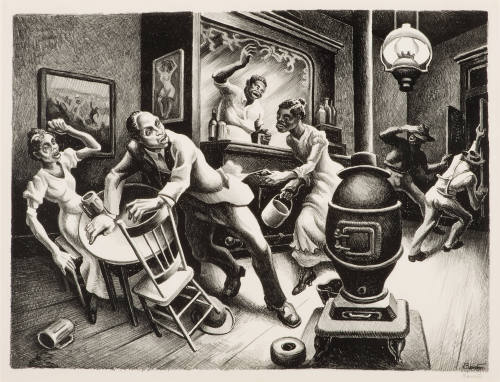

In Benton’s lithograph, six African American figures fill the space of a nightclub: Frankie in the center, Johnnie, his lover, the barkeeper, and two fleeing men. Benton chose the moment when Frankie fires the first shot at Johnnie; she has yet to deliver the fatal blow. In a desperate scramble to escape, Johnnie knocks over a table and chair as he looks back at her with open-mouthed shock. In the foreground of the composition, a potbellied stove and kerosene lamp mirror the curving forms of the human figures.

The story is probably based on an actual murder that took place in 1899. [1] The drama that unfolds in this image is from the sixth verse of a folk song accredited to St. Louis composer Jim Dooley:

Johnnie he grabbed off his Stetson,

“Oh-my-God, Frankie, don’t shoot.”

But Frankie put her finger on the trigger,

And her gun went root-a-toot-toot.

She shot her man,

‘Cause he done her wrong. [2]

Benton selected the scene from the popular folk song because, according to the artist, it is representative of Missouri mythology. Throughout his work, Benton attempted to reconstruct history through folk stories and popular culture. Rather than telling only the histories of great men, Benton sometimes chose stories that uncovered the dark underbelly of a particular time or place.

Notes:

[1] George D. Hendricks, “Frankie and Johnny,” in Western Folklore 23, no. 3 (July 1964), 203.

[2] Creekmore Fath, The Lithographs of Thomas Hart Benton (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 1979), 42.

ProvenanceTo 1987

Stuart P. Feld (born 1935), New York, NY [1]

From 1987

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC, given by Stuart P. Feld on September 28, 1987. [2]

Notes:

[1] Letter from Stuart P. Feld, September 16, 1987.

[2] See note 1. Also, shipping invoice notes works were received September 28, 1987.

Exhibition History2011

Thomas Hart Benton: America’s Master Storyteller

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC (3/3/2011-7/31/2011)

2018

Outlaws in American Art

Reynolda House Museum of American Art (February 28, 2018 - December 2, 2018)

2022-2023

Prohibition Days: Conserving Thomas Hart Benton's Bootleggers

Reynolda House Museum of American Art (12/2/2022 - 5/28/2023)

Published ReferencesFath, Creekmore. The Lithographs of Thomas Hart Benton. Austin: University of Texas Press: 1979, no. 11.

Wolff, Kurt, "The ballad of Frankie and Johnny" Songlines: Journeys In World Music. no. 8 (Autumn-Winter 2000): 30-1.

DepartmentAmerican Art

Frankie and Johnnie

Artist

Thomas Hart Benton

(1889 - 1975)

Date1936

Mediumlithograph

DimensionsFrame: 28 1/8 x 33 5/8 in. (71.4 x 85.4 cm)

Image: 16 1/8 x 22 1/8 in. (41 x 56.2 cm)

SignedBenton

Credit LineGift of Stuart P. Feld

Copyright© 2021 T.H. Benton and R.P. Benton Trusts / Licensed by VAGA at Artist Rights Society (ARS), NY

Object number1987.2.1

DescriptionThomas Hart Benton’s choice of lithography for his forays into printmaking is a logical extension of his egalitarian attitude. The medium originated in the mid-nineteenth century and was used early on for newspaper illustrations. Its relative inexpensiveness was one of the reasons the process was revived in the 1920s and 1930s. Frankie and Johnnie is one of four lithographs produced in conjunction with Benton’s Missouri State Capitol Building murals from the mid-1930s. In a print marked by detail, dramatic action, and fluid line, Benton depicted a scene derived from an American folk song about a scorned lover and a violent act.In Benton’s lithograph, six African American figures fill the space of a nightclub: Frankie in the center, Johnnie, his lover, the barkeeper, and two fleeing men. Benton chose the moment when Frankie fires the first shot at Johnnie; she has yet to deliver the fatal blow. In a desperate scramble to escape, Johnnie knocks over a table and chair as he looks back at her with open-mouthed shock. In the foreground of the composition, a potbellied stove and kerosene lamp mirror the curving forms of the human figures.

The story is probably based on an actual murder that took place in 1899. [1] The drama that unfolds in this image is from the sixth verse of a folk song accredited to St. Louis composer Jim Dooley:

Johnnie he grabbed off his Stetson,

“Oh-my-God, Frankie, don’t shoot.”

But Frankie put her finger on the trigger,

And her gun went root-a-toot-toot.

She shot her man,

‘Cause he done her wrong. [2]

Benton selected the scene from the popular folk song because, according to the artist, it is representative of Missouri mythology. Throughout his work, Benton attempted to reconstruct history through folk stories and popular culture. Rather than telling only the histories of great men, Benton sometimes chose stories that uncovered the dark underbelly of a particular time or place.

Notes:

[1] George D. Hendricks, “Frankie and Johnny,” in Western Folklore 23, no. 3 (July 1964), 203.

[2] Creekmore Fath, The Lithographs of Thomas Hart Benton (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 1979), 42.

ProvenanceTo 1987

Stuart P. Feld (born 1935), New York, NY [1]

From 1987

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC, given by Stuart P. Feld on September 28, 1987. [2]

Notes:

[1] Letter from Stuart P. Feld, September 16, 1987.

[2] See note 1. Also, shipping invoice notes works were received September 28, 1987.

Exhibition History2011

Thomas Hart Benton: America’s Master Storyteller

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC (3/3/2011-7/31/2011)

2018

Outlaws in American Art

Reynolda House Museum of American Art (February 28, 2018 - December 2, 2018)

2022-2023

Prohibition Days: Conserving Thomas Hart Benton's Bootleggers

Reynolda House Museum of American Art (12/2/2022 - 5/28/2023)

Published ReferencesFath, Creekmore. The Lithographs of Thomas Hart Benton. Austin: University of Texas Press: 1979, no. 11.

Wolff, Kurt, "The ballad of Frankie and Johnny" Songlines: Journeys In World Music. no. 8 (Autumn-Winter 2000): 30-1.

Status

Not on viewCollections