Skip to main content

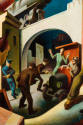

In Bootleggers, Benton combined several dramatic vignettes to create a complex narrative that explores the seamy underside of illegal liquor trafficking during Prohibition. Using a circular composition that emphasizes the cause-and-effect nature of the trafficking cycle, Benton presents a corrupt, formally-attired capitalist paying off a bootlegger who pulls bottles out of a crate, an anonymous laborer loading yet more crates onto a plane, another plane in flight, and a violent hold-up taking place in front of a complicit police officer. In the center of the composition, a train powers across the cityscape, undoubtedly transporting more illegal goods.

The figures are articulated in the artist’s familiar sinuous, almost distorted style. The intense modeling of the figures may be attributed to Benton’s practice of making clay maquettes of his painting compositions before creating them on the canvas. Roger Medearis, a student of Benton’s at the Kansas City Art Institute in 1938, described the artist’s technique for the 1938–1939 painting Persephone in this way: “I watched Benton make detailed drawings…. For the first time, I saw one of his three-dimensional clay models, finished in bright colors. He made two broadly painted sketches as studies for color and tone values. As I looked on, he enlarged his basic drawing by sketching it onto the big canvas, divided by grid lines. He continued by establishing the underpainting in umber tones. I learned how he mixed his egg tempera—rapidly dipping his brush in egg yolk, water, and jars of dry pigment and mixing them on a sheet of glass—before he applied the paint to the canvas with powerful wrist actions, wielding large, stiff brushes, or adding details with the most delicate touches of a small brush, his little figure elevated as if he held a fragile cup of tea.” [2]

Benton used the airplane, train, and automobile to emphasize the modern setting of the painting. The artist had long been drawn to machines; indeed, he attributed a change in his style of painting, from abstract to more representational, in part to his fascination with the new machines he encountered during his service in World War I: “The new airplanes, the blimps, the dredges, because they were so interesting in themselves, tore me away from all my grooved habits, from my play with colored cubes and classic attenuations, from my aesthetic drivelings and morbid self-concerns.” [3]

In his autobiography An Artist in America, Benton noted that, in the late 1920s, his “mind was full of painting an industrial history of America.” He detailed in particular his fascination with the machines of the industrial landscape: “I got into the great steel mills, ship-building plants, and other industrial concerns of the country. I made hundreds of drawings of furnaces, convertors, cranes, drills, dredges, and compressors, rigs, and pumps, rakes, tractors, combines, and old fashioned threshing machines. I stuck my nose into everything.” [4] Benton portrayed the machines in Bootleggers as tools used to exploit workingmen for the benefit of the wealthy and corrupt: the airplane looms over the stoop-shouldered laborer, the train spews toxic red steam. Far from the streamlined vehicles of Benton’s Precisionist peers—hallmarks of a new capitalist utopia—Benton’s machines contributed to man’s oppression.

The painting thus stands as a harsh critique of the corrupting influences of modern society, and the artist further distanced himself from the twentieth century by paying homage to Renaissance and Baroque artists through his Mannerist figures and classical poses. As Barbara Millhouse and Robert Workman noted in American Originals, “The rippling contours and elongation of his shirt-sleeved arm recall El Greco, a newly discovered Old Master who had considerable influence on the formation of Benton’s mature style. On the right, a pilot in the cockpit of an airplane resembling The Spirit of St. Louis waits for the illegal cargo to be loaded by an anonymous laborer, whose pose resembles Renaissance renditions of Christ carrying his cross to Calvary.” [5] However, the blocky forms of the buildings, the smooth planes, and the converging diagonals all convey a decidedly modernist interest in form. Benton was adamant, however, that his primary concern in creating the painting was its social and historical context. In another letter to Barbara Millhouse, he wrote, “How could you possibly understand Bootleggers without knowing the social conditions which inspired it? True the picture is a Form, but it is also more than that—more than just a series of ‘plastic relations,’ I mean.” And later, he wrote, “The picture you have represents my first shift into a muralistic style which aimed at ‘containing’ the life of my time, ‘The American Life,’ I should say. It is the predecessor of all the later muralistic paintings on American Life as we experience it.” [6]

Notes:

[1] Matthew Baigell, Thomas Hart Benton (New York: Harry N. Abrams Co., 1973), 111, and Benton to Millhouse, October 20, 1971. Object file, Reynolda House Museum of American Art.

[2] Roger Medearis, “Student of Thomas Hart Benton,” Smithsonian Studies in American Art 4, no.3/4 (Summer-Autumn 1990), 50–52.

[3] Henry Adams, Thomas Hart Benton, An American Original (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1989), 87.

[4] Thomas Hart Benton, An Artist in America, 4th ed. (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1983), 86 and 81.

[5] Charles C. Eldredge, Barbara Babcock Millhouse, and Robert G. Workman, American Originals: Selections from Reynolda House, Museum of American Art (New York: Abbeville Press, 1990), 110.

[6] Benton to Barbara Babcock Millhouse, August 6, and October 20, 1971. Object file, Reynolda House Museum of American Art.

ProvenanceTo 1968

Thomas Hart Benton (1889-1975), Kansas City, MO [1]

1968

James Graham & Sons, New York, NY [2]

From 1971

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC, purchased from James Graham & Sons with funds from Barbara B. Millhouse on June 21, 1971 [3]

Notes:

[1] Correspondence from the James Graham & Sons gallery, June 4, 1984, object file.

[2] Graham Gallery (James Graham & Sons) invoice, June 21, 1971, object file.

[3] See note 2.

Exhibition History1930

125th Annual Exhibition

Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Philadelphia, PA (1/26/1930-3/16/1930)

Cat. No. 78

1930

Twenty-Fifth Annual Exhibition of Selected Paintings by American Artists

Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY (4/26/1930-6/22/1930 )

Cat. No. 12

Exhibited as "The Smugglers"

1930

Twenty-Fifth Annual Exhibition Of Paintings By American Artists

Saint Louis Art Museum, St. Louis, MO (9/20/1930-11/2/1930)

Cat. No. 5

Exhibited as "The Smugglers"

1930

43rd Annual Exhibition of American Paintings and Sculpture

The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL (10/30/1930-12/14/1930)

Cat No. 14

Exhibited as "The Smugglers"

1934

A Century Of Progress: Exhibition Of Paintings And Sculpture

The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL (6/1/1934-11/1/1934)

Cat. No. 527

Lent by the artist

1937

Drawings and Paintings by Thomas Hart Benton

Lakeside Press Galleries, Chicago, IL (10/1937-11/1937)

Lent by the artist

1968

Thomas Hart Benton

James Graham & Sons, New York, NY (1968)

1971

What Is American Art

M. Knoedler & Co., New York, NY (1971)

Cat. No. 104

1972

Thomas Hart Benton: A Retrospective Of His Early Years 1907-1929

Rutgers University Art Gallery, New Brunswick, NJ (11/1972-12/1972)

Cat. No. 60

1989-1990

Thomas Hart Benton Centennial Exhibition

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO (4/16/1989-6/18/1989)

The Detroit Institute of Art, Detroit, MI (8/4/1989-10/15/1989)

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY (11/16/1989-2/11/1990)

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, CA (4/26/1990-7/22/1990)

1990-1992

American Originals, Selections From Reynolda House Museum Of American Art The American Federation of Arts

Center for the Fine Arts, Miami, FL (9/22/1990-11/18/1990)

Palm Springs Desert Museum, Palm Springs, CA (12/16/1990-2/10/1991)

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY (3/6/1991-5/11/1991)

Memphis Brooks Museum of Art, Memphis, TN (6/2/1991-7/28/1991)

Amon Carter Museum of Western Art, Fort Worth, TX (8/17/1991-10/20/1991)

Terra Museum of American Art, Chicago, IL (11/17/1991-1/12/1992)

The Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, OK (3/1/1992-4/26/1992)

1999

The American Century: Art and Culture, 1900-2000 (Part I: 1900-1950)

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York NY (4/22/1999 -8/22/1999)

2005

Vanguard Collecting: American Art at Reynolda House

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC (4/1/2005-8/21/2005)

2007

Wings of Adventure: Z. Smith Reynolds and the Flight of 898 Whiskey

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC (9/8/2007-12/30/2007)

2011

Thomas Hart Benton: America’s Master Storyteller

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC (3/3/2011-7/31/2011)

2013-2014

Partisans: Social Realism in American Art

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC (10/5/2013-3/9/2014)

2015

American Epics: Thomas Hart Benton and Hollywood

Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, MA (6/6/2015-5/1/2016)

2021

The Voyage of Life: Art, Allegory, and Community Response

Reynolda House Museum of American Art (7/16/2021 - 12/12/2021)

2022-2023

Prohibition Days: Conserving Thomas Hart Benton's Bootleggers

Reynolda House Museum of American Art (12/2/2022 - 5/28/2023)

Published ReferencesAdams, Henry. Thomas Hart Benton, An American Original. New York : Knopf : Distributed by Random House, c1989: 131.

Baigell, Matthew. Thomas Hart Benton New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1974: 111, 129 (illustration).

Benton, Thomas Hart. American In Art: A Professional And Technical Autobiography. Lawrence: The University Press of Kansas, 1969: 89 (illustration).

Campbell, Lawrence. "Things are Thoughts in America," Art News. 69 (February 1971): 37 (illustration).

Drowne, Kathleen. Spirits Of Defiance: National Prohibition & Jazz Age Literature, 1920-1933. Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 2005.

Eldredge, Charles C. "The Paintings at Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston Salem, North Carolina," Antiques. v.142 (November 1992): 700 (illustration).

Fahlman, Betsy. James Graham and Sons, A Century and a Half in the Art Business, 1857-2007. New York: James Graham & Sons, 2007: fig. 52.

Garrity, John. "Spit and Vinegar: At his centennial, Tom Benton still riles the critics." Connoisseur v. 219, #927 (April 1989): 132.

Haskell, Barbara. The American Century: Art And Culture 1900-1950. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, in association with W.W. Norton & Company, 1999: 183.

Hutton, Kathleen and Wanda Urbanska. "Examining Prejudice Through Art: Reynolda House, Museum of American Art," Art Education v. 50, no. 5 (September 11997): 25-28; illus., 28.

Marling, Karal Ann. Tom Benton And His Drawings: A Biographical Essay And A Collection Of His Sketches, Studies, And Mural Cartoons. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1985: 104.

Mead, Margaret and Galas, Nicholas. "What is American in American Art?", Arts Magazine. v. 45 (May 1971): 32 (illustration).

Millhouse, Barbara B. & Workman, Robert. American Originals. New York: Abbeville Press Publishers, 1990: 110-111.

Reynolda House Annual Report, September 2003.

American Epics: Thomas Hart Benton and Hollywood. ed. by Austen Barron Bailly. Peabody Essex Museum, 2015: 92-93.

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Reynolda: Her Muses, Her Stories , with contributions by Martha R. Severens and David Park Curry (Winston-Salem, N.C.: Reynolda House Museum of American Art affiliated with Wake Forest University, 2017). pg. 46, 130, 131

DepartmentAmerican Art

Bootleggers

Artist

Thomas Hart Benton

(1889 - 1975)

Date1927

Mediumegg tempera, oil, and acrylic on canvas mounted to aluminum panel

DimensionsFrame: 68 3/4 x 74 3/4 in. (174.6 x 189.9 cm)

Image: 65 x 72 in. (165.1 x 182.9 cm)

SignedBenton

Credit LineMuseum Purchase with funds provided by Barbara B. Millhouse

Copyright© 2021 T.H. Benton and R.P. Benton Trusts / Licensed by VAGA at Artist Rights Society (ARS), NY

Object number1971.2.1

DescriptionThomas Hart Benton painted Bootleggers, 1927, during a pivotal time in his career. Its large scale reflects his recent mural project, the American Historical Epic series. But the contemporary setting, in the Prohibition era of the 1920s, points the way toward his next project, a series he called America Today. As he noted in a letter to Barbara Babcock Millhouse, who purchased the painting in 1971, the painting was his “first entrance into painting ‘history, which was not history when it was painted but became history with the passage of time.’” [1]In Bootleggers, Benton combined several dramatic vignettes to create a complex narrative that explores the seamy underside of illegal liquor trafficking during Prohibition. Using a circular composition that emphasizes the cause-and-effect nature of the trafficking cycle, Benton presents a corrupt, formally-attired capitalist paying off a bootlegger who pulls bottles out of a crate, an anonymous laborer loading yet more crates onto a plane, another plane in flight, and a violent hold-up taking place in front of a complicit police officer. In the center of the composition, a train powers across the cityscape, undoubtedly transporting more illegal goods.

The figures are articulated in the artist’s familiar sinuous, almost distorted style. The intense modeling of the figures may be attributed to Benton’s practice of making clay maquettes of his painting compositions before creating them on the canvas. Roger Medearis, a student of Benton’s at the Kansas City Art Institute in 1938, described the artist’s technique for the 1938–1939 painting Persephone in this way: “I watched Benton make detailed drawings…. For the first time, I saw one of his three-dimensional clay models, finished in bright colors. He made two broadly painted sketches as studies for color and tone values. As I looked on, he enlarged his basic drawing by sketching it onto the big canvas, divided by grid lines. He continued by establishing the underpainting in umber tones. I learned how he mixed his egg tempera—rapidly dipping his brush in egg yolk, water, and jars of dry pigment and mixing them on a sheet of glass—before he applied the paint to the canvas with powerful wrist actions, wielding large, stiff brushes, or adding details with the most delicate touches of a small brush, his little figure elevated as if he held a fragile cup of tea.” [2]

Benton used the airplane, train, and automobile to emphasize the modern setting of the painting. The artist had long been drawn to machines; indeed, he attributed a change in his style of painting, from abstract to more representational, in part to his fascination with the new machines he encountered during his service in World War I: “The new airplanes, the blimps, the dredges, because they were so interesting in themselves, tore me away from all my grooved habits, from my play with colored cubes and classic attenuations, from my aesthetic drivelings and morbid self-concerns.” [3]

In his autobiography An Artist in America, Benton noted that, in the late 1920s, his “mind was full of painting an industrial history of America.” He detailed in particular his fascination with the machines of the industrial landscape: “I got into the great steel mills, ship-building plants, and other industrial concerns of the country. I made hundreds of drawings of furnaces, convertors, cranes, drills, dredges, and compressors, rigs, and pumps, rakes, tractors, combines, and old fashioned threshing machines. I stuck my nose into everything.” [4] Benton portrayed the machines in Bootleggers as tools used to exploit workingmen for the benefit of the wealthy and corrupt: the airplane looms over the stoop-shouldered laborer, the train spews toxic red steam. Far from the streamlined vehicles of Benton’s Precisionist peers—hallmarks of a new capitalist utopia—Benton’s machines contributed to man’s oppression.

The painting thus stands as a harsh critique of the corrupting influences of modern society, and the artist further distanced himself from the twentieth century by paying homage to Renaissance and Baroque artists through his Mannerist figures and classical poses. As Barbara Millhouse and Robert Workman noted in American Originals, “The rippling contours and elongation of his shirt-sleeved arm recall El Greco, a newly discovered Old Master who had considerable influence on the formation of Benton’s mature style. On the right, a pilot in the cockpit of an airplane resembling The Spirit of St. Louis waits for the illegal cargo to be loaded by an anonymous laborer, whose pose resembles Renaissance renditions of Christ carrying his cross to Calvary.” [5] However, the blocky forms of the buildings, the smooth planes, and the converging diagonals all convey a decidedly modernist interest in form. Benton was adamant, however, that his primary concern in creating the painting was its social and historical context. In another letter to Barbara Millhouse, he wrote, “How could you possibly understand Bootleggers without knowing the social conditions which inspired it? True the picture is a Form, but it is also more than that—more than just a series of ‘plastic relations,’ I mean.” And later, he wrote, “The picture you have represents my first shift into a muralistic style which aimed at ‘containing’ the life of my time, ‘The American Life,’ I should say. It is the predecessor of all the later muralistic paintings on American Life as we experience it.” [6]

Notes:

[1] Matthew Baigell, Thomas Hart Benton (New York: Harry N. Abrams Co., 1973), 111, and Benton to Millhouse, October 20, 1971. Object file, Reynolda House Museum of American Art.

[2] Roger Medearis, “Student of Thomas Hart Benton,” Smithsonian Studies in American Art 4, no.3/4 (Summer-Autumn 1990), 50–52.

[3] Henry Adams, Thomas Hart Benton, An American Original (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1989), 87.

[4] Thomas Hart Benton, An Artist in America, 4th ed. (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1983), 86 and 81.

[5] Charles C. Eldredge, Barbara Babcock Millhouse, and Robert G. Workman, American Originals: Selections from Reynolda House, Museum of American Art (New York: Abbeville Press, 1990), 110.

[6] Benton to Barbara Babcock Millhouse, August 6, and October 20, 1971. Object file, Reynolda House Museum of American Art.

ProvenanceTo 1968

Thomas Hart Benton (1889-1975), Kansas City, MO [1]

1968

James Graham & Sons, New York, NY [2]

From 1971

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC, purchased from James Graham & Sons with funds from Barbara B. Millhouse on June 21, 1971 [3]

Notes:

[1] Correspondence from the James Graham & Sons gallery, June 4, 1984, object file.

[2] Graham Gallery (James Graham & Sons) invoice, June 21, 1971, object file.

[3] See note 2.

Exhibition History1930

125th Annual Exhibition

Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Philadelphia, PA (1/26/1930-3/16/1930)

Cat. No. 78

1930

Twenty-Fifth Annual Exhibition of Selected Paintings by American Artists

Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY (4/26/1930-6/22/1930 )

Cat. No. 12

Exhibited as "The Smugglers"

1930

Twenty-Fifth Annual Exhibition Of Paintings By American Artists

Saint Louis Art Museum, St. Louis, MO (9/20/1930-11/2/1930)

Cat. No. 5

Exhibited as "The Smugglers"

1930

43rd Annual Exhibition of American Paintings and Sculpture

The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL (10/30/1930-12/14/1930)

Cat No. 14

Exhibited as "The Smugglers"

1934

A Century Of Progress: Exhibition Of Paintings And Sculpture

The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL (6/1/1934-11/1/1934)

Cat. No. 527

Lent by the artist

1937

Drawings and Paintings by Thomas Hart Benton

Lakeside Press Galleries, Chicago, IL (10/1937-11/1937)

Lent by the artist

1968

Thomas Hart Benton

James Graham & Sons, New York, NY (1968)

1971

What Is American Art

M. Knoedler & Co., New York, NY (1971)

Cat. No. 104

1972

Thomas Hart Benton: A Retrospective Of His Early Years 1907-1929

Rutgers University Art Gallery, New Brunswick, NJ (11/1972-12/1972)

Cat. No. 60

1989-1990

Thomas Hart Benton Centennial Exhibition

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO (4/16/1989-6/18/1989)

The Detroit Institute of Art, Detroit, MI (8/4/1989-10/15/1989)

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY (11/16/1989-2/11/1990)

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, CA (4/26/1990-7/22/1990)

1990-1992

American Originals, Selections From Reynolda House Museum Of American Art The American Federation of Arts

Center for the Fine Arts, Miami, FL (9/22/1990-11/18/1990)

Palm Springs Desert Museum, Palm Springs, CA (12/16/1990-2/10/1991)

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY (3/6/1991-5/11/1991)

Memphis Brooks Museum of Art, Memphis, TN (6/2/1991-7/28/1991)

Amon Carter Museum of Western Art, Fort Worth, TX (8/17/1991-10/20/1991)

Terra Museum of American Art, Chicago, IL (11/17/1991-1/12/1992)

The Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, OK (3/1/1992-4/26/1992)

1999

The American Century: Art and Culture, 1900-2000 (Part I: 1900-1950)

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York NY (4/22/1999 -8/22/1999)

2005

Vanguard Collecting: American Art at Reynolda House

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC (4/1/2005-8/21/2005)

2007

Wings of Adventure: Z. Smith Reynolds and the Flight of 898 Whiskey

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC (9/8/2007-12/30/2007)

2011

Thomas Hart Benton: America’s Master Storyteller

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC (3/3/2011-7/31/2011)

2013-2014

Partisans: Social Realism in American Art

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC (10/5/2013-3/9/2014)

2015

American Epics: Thomas Hart Benton and Hollywood

Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, MA (6/6/2015-5/1/2016)

2021

The Voyage of Life: Art, Allegory, and Community Response

Reynolda House Museum of American Art (7/16/2021 - 12/12/2021)

2022-2023

Prohibition Days: Conserving Thomas Hart Benton's Bootleggers

Reynolda House Museum of American Art (12/2/2022 - 5/28/2023)

Published ReferencesAdams, Henry. Thomas Hart Benton, An American Original. New York : Knopf : Distributed by Random House, c1989: 131.

Baigell, Matthew. Thomas Hart Benton New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1974: 111, 129 (illustration).

Benton, Thomas Hart. American In Art: A Professional And Technical Autobiography. Lawrence: The University Press of Kansas, 1969: 89 (illustration).

Campbell, Lawrence. "Things are Thoughts in America," Art News. 69 (February 1971): 37 (illustration).

Drowne, Kathleen. Spirits Of Defiance: National Prohibition & Jazz Age Literature, 1920-1933. Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 2005.

Eldredge, Charles C. "The Paintings at Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston Salem, North Carolina," Antiques. v.142 (November 1992): 700 (illustration).

Fahlman, Betsy. James Graham and Sons, A Century and a Half in the Art Business, 1857-2007. New York: James Graham & Sons, 2007: fig. 52.

Garrity, John. "Spit and Vinegar: At his centennial, Tom Benton still riles the critics." Connoisseur v. 219, #927 (April 1989): 132.

Haskell, Barbara. The American Century: Art And Culture 1900-1950. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, in association with W.W. Norton & Company, 1999: 183.

Hutton, Kathleen and Wanda Urbanska. "Examining Prejudice Through Art: Reynolda House, Museum of American Art," Art Education v. 50, no. 5 (September 11997): 25-28; illus., 28.

Marling, Karal Ann. Tom Benton And His Drawings: A Biographical Essay And A Collection Of His Sketches, Studies, And Mural Cartoons. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1985: 104.

Mead, Margaret and Galas, Nicholas. "What is American in American Art?", Arts Magazine. v. 45 (May 1971): 32 (illustration).

Millhouse, Barbara B. & Workman, Robert. American Originals. New York: Abbeville Press Publishers, 1990: 110-111.

Reynolda House Annual Report, September 2003.

American Epics: Thomas Hart Benton and Hollywood. ed. by Austen Barron Bailly. Peabody Essex Museum, 2015: 92-93.

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Reynolda: Her Muses, Her Stories , with contributions by Martha R. Severens and David Park Curry (Winston-Salem, N.C.: Reynolda House Museum of American Art affiliated with Wake Forest University, 2017). pg. 46, 130, 131

Status

Not on view