Skip to main content

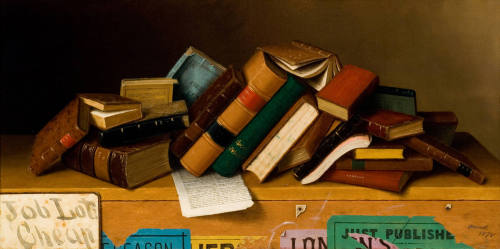

The books themselves are a mixture of leather- and paper-bound, finely- and cheaply-made volumes. Some are stamped with gold, others are simply printed with black ink. The range of unrelated volumes demonstrates the booksellers’ practice of gathering random unsold titles and offering the entire group (the “job lot”) at a discounted price (“cheap”).

Books and printed matter occupied Harnett throughout his career, but particularly in 1878 and 1879. Job Lot Cheap, however, is unusual for the absence of any other type of object, such as the candles, currency, newspapers, mugs, musical instruments, pipes, and letters that Harnett often chose to group with the books. The jumbled volumes and the label-covered packing crate are the only objects in the piece. Art historian Andrew Walker has identified the titles of four books in the painting: Homer’s Odyssey, Cyclopaedia Americana/Vol. II, Arabian Nights, and Alexandre Dumas’s Forty-Five Guardsmen.

Most of the debate surrounding Harnett’s work centers around the issue of meaning. Nineteenth-century critics sometimes dismissed Harnett’s work as mere imitation lacking a message or narrative to give the image meaning. This attitude persisted into the twentieth century; the painter Marsden Hartley wrote that “there is no interpretation in Harnett, there is nothing to bother about, nothing to confuse, nothing to interpret, there are in the common sense no mind-workings—there is the myopic persistence to render every single thing, singly” (Hartley, Marsden. On Art by Marsden Hartley, ed. Gail R. Scott [New York: Horizon Press, 1982], pp. 178-79). Harnett’s biographer Alfred Frankenstein, the author of the first serious study of the artist’s work in the twentieth century, also dismissed any attempt to find meaning in Harnett’s art (quoted in Groseclose, Barbara S. “Vanity and the Artist: Some Still-Life Paintings by William Michael Harnett,” in American Art Journal 19, 1 (1987), p. 52).

Harnett, however, famously claimed in one of the few interviews he ever gave, “I endeavor to make the composition tell a story” (quoted in Bolger, Doreen, Marc Simpson, and John Wilmerding. William M. Harnett. Exh. cat. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1992, p. xv). This argument is supported by an essay by art historian Marc Simpson on Harnett’s inclusion of musical instruments and sheet music. Simpson notes that Harnett was himself a musician and an avid opera enthusiast. The inclusion of objects related to music, then, must have been meaningful to Harnett; he did not choose them simply for random or aesthetic reasons (Simpson, Marc. “Harnett and Music: Many a Touching Melody,” in Bolger, Doreen, Marc Simpson, and John Wilmerding. William M. Harnett. Exh. cat. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1992, p. 289).

Several art historians have attempted to puzzle out the meaning of the books in Job Lot Cheap. Charles Eldredge noted that three of the books represent a continent (Europe for The Odyssey, America for the encyclopedia, and Asia for Arabian Nights), and that the fact that only the encyclopedia is placed rightside up might indicate Harnett’s political allegiance to his native land (Eldredge, Charles C., Barbara Babcock Millhouse, and Robert G. Workman. American Originals: Selections from Reynolda House, Museum of American Art. New York: Abbeville Press, 1990, p. 84). Andrew Walker has suggested that Harnett was referencing the passage of time since, by 1878, this type of bookselling had been replaced by more modern commercial ventures such as department stores. Walker further points out that the purchaser of the painting, Byron Nugent, was the owner of a large and successful department store in Saint Louis, and thus might have appreciated this nostalgic look at the old ways of doing business.

Nostalgia also plays a role in Harnett’s most overtly vanitas pieces. Beginning in 1876 and ending in 1879, a period which includes the execution of Job Lot Cheap, Harnett did a series of paintings of books with vanitas elements such as skulls, hourglasses, and snuffed-out candles. Still life painting has long been associated with vanitas, the passage of time and the inevitability of death. Still life paintings for centuries have featured fruit and flowers that fade, skulls that remind the viewer of death, and candles with a wisp of smoke indicating the extinguished flame.

While art historian Barbara Groseclose has proposed that Harnett’s vanitas paintings evoke not only the brevity of life but also the futility of human attempts to surmount death with artistic and literary creations (Groseclose, Barbara S. “Vanity and the Artist: Some Still-Life Paintings by William Michael Harnett,” in American Art Journal 19, 1 (1987), pp. 51-59), the absence in Job Lot Cheap of traditional vanitas elements such as skulls and candles might suggest a more hopeful reading. Although it is true that both the books depicted and, by extension, Harnett’s own painting, are for sale, they will continue to live on even if sold off. Perhaps in this case, Harnett is using his painting to convey the permanence of the written word and the painted canvas—indeed, of all of man’s artistic endeavors.

ProvenanceByron Nugent (1842 – 1908), St. Louis MO [1]

Julian Nugent (born 1893), St. Louis MO and Colorado Springs, CO [2]

To 1966

William Middendorf II (born 1924) , New York NY [3]

1966

Kennedy Galleries, Inc. New York NY [4]

From 1966

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem NC [5]

Notes:

[1] Reynolda House cover sheet 1981, object file.

[2] See note 1.

[3] See note 1.

[4] Bill of sale, object file.

[5] See note 4.

Exhibition HistoryPeale House Galleries, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia PA (Lent by John Middendorf II)

1966

Two Illusionist Painters- Harnett, Peto

Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Philadelphia PA (1966)

Cat. No. 9

1970

The Reality Of Appearance: The Trompe l'Oeil Tradition In American Painting

National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. (3/21/1970-5/3/1970)

Whitney Museum, New York NY (5/18/1970-7/5/1970)

University Art Museum, Berkeley CA and California Palace of the Legion of Honor, San Francisco CA (7/15/1970-8/31/1970)

Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit MI (9/15/1970-10/31/1970)

Cat. No. 27

1971

Reynolda House American Paintings

Hirschl and Adler Galleries, Inc., New York NY (1/13/1971-1/31/1971)

Cat. No.19

For the Benefit of the Smith College Scholarship Fund

1980

Plane Truth: American Trompe L'oeil Painting

Katonah Gallery, Katonah NY (6/7/1980 - 7/20/1980)

Cat. No.22

1981-1982

Painters of the Humble Truth: Masterpieces of American Still Life

Philbrook Art Center, Tulsa OK (9/27/1981-11/1/1981)

Oakland Museum, Oakland CA (12/1981-1/1982)

Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore MD (3/1982-4/1982)

National Academy of Design Museum, New York NY (5/1982-7/1982)

1990-1992

American Originals, Selections From Reynolda House Museum Of American Art

The American Federation of Arts:

Center for the Fine Arts, Miami FL (9/22/1990-11/18/1990)

Palm Springs Desert Museum, Palm Springs CA (12/16/1990-2/10/1991)

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York NY (3/6/1991-5/11/1991)

Memphis Brooks Museum of Art, Memphis TN (6/2/1991-7/28/1991)

Amon Carter Museum of Western Art, Fort Worth TX (8/17/1991-10/20/1991)

Terra Museum of American Art, Chicago IL (11/17/1991-1/12/1992)

The Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, OK (3/1/1992-4/26/1992)

1992-1993

The Still Life Painting Of William M. Harnett

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York NY (3/14/1992-6/14/1992)

Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth TX (7/18/1992-10/18/1992)

Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, San Francisco CA (11/14/1992-2/14/1993)

National Gallery of Art, Washington DC (3/14/1993-6/13/1993)

2005

Vanguard Collecting: American Art At Reynolda House

Reynolda Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem NC (4/1/2005-8/21/2005)

2010 - 2011

Taxing Visions: Financial Episodes in Late Nineteenth-Century American Painting

Palmer Museum of Art (9/28/2010 - 12/19/2010)

The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens (1/29/2011 - 5/30/2011)

2017

Samuel F.B. Morse's Gallery of the Louvre and the Art of Invention

Reynolda House Museum of American Art (02/17/2017 - 06/04/2017)

Published ReferencesLubin, David. Picturing A Nation: Art And Social Change In Nineteenth- Century America New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994: 296.

Silverstein, Michael and Greg Urban. Natural Histories Of Discourse Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1996: illus. cover.

INSIGHTS: The Faculty Journal of Austin Seminary 116, no. 1 (Fall 2000): cover illus.

Richards, Marion K. College Teaching: The Examined Life of a Humanities Professor Vol 36/No 4 (Fall 1988): 135-139.

Dry Goods Economist November 1, 1892.

Frankenstein, A. After The Hunt (1953): 45, 46-48, 52, 110, 168.

Lassiter, Barbara B. Reynolda House American Paintings. Winston-Salem, NC: Reynolda House, Inc., 1971: 40, illus. 41.

Millhouse, Barbara B. and Robert Workman. American Originals New York: Abbeville Press Publishers, 1990: 82-5.

Hutson, Martha. “William M Harnett.” American Art Review v.5 no.1 (Summer 1992): 80-83.

Burgard, Timothy Anglin. Masterworks of American Painting at the de Young. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 2005.

Mazow, Leo and Kevin Murphy. Taxing Visions: Financial Episodes in Late Nineteenth-Century American Art. Pennsylvania State University Press, 2010.

Bolger, Doreen and Marc Simpson. William M. Harnett. Harry N Abrams, 1992, exhib. cat.

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Reynolda: Her Muses, Her Stories , with contributions by Martha R. Severens and David Park Curry (Winston-Salem, N.C.: Reynolda House Museum of American Art affiliated with Wake Forest University, 2017). pg. 30, 31, 41, 98, 99, 128, 194

DepartmentAmerican Art

Job Lot Cheap

Artist

William Michael Harnett

(1848 - 1892)

Date1878

Mediumoil on canvas

DimensionsFrame: 25 1/8 x 43 1/4 in. (63.8 x 109.9 cm)

Image: 18 x 36 in. (45.7 x 91.4 cm)

SignedWMH (monogram) arnett 1878

Credit LineOriginal Purchase Fund from the Mary Reynolds Babcock Foundation, Z. Smith Reynolds Foundation, ARCA, and Anne Cannon Forsyth

CopyrightPublic Domain

Object number1966.2.10

DescriptionA relatively early painting in Harnett’s oeuvre, created just four years after the artist completed his first work in oil, Job Lot Cheap nevertheless demonstrates Harnett’s astonishing illusionistic skill. The painting shows a jumble of books for sale, arranged haphazardly on a wooden book crate placed close to the picture plane. The crate bears several labels, mostly illegible, as Harnett has cropped the image so that the words are cut off. On one green label, the viewer can make out the words “JUST PUBLISHE …” but the final D has been torn off. In the lower left corner, the words “Job Lot Cheap” have been painted on the inside of an old book cover.The books themselves are a mixture of leather- and paper-bound, finely- and cheaply-made volumes. Some are stamped with gold, others are simply printed with black ink. The range of unrelated volumes demonstrates the booksellers’ practice of gathering random unsold titles and offering the entire group (the “job lot”) at a discounted price (“cheap”).

Books and printed matter occupied Harnett throughout his career, but particularly in 1878 and 1879. Job Lot Cheap, however, is unusual for the absence of any other type of object, such as the candles, currency, newspapers, mugs, musical instruments, pipes, and letters that Harnett often chose to group with the books. The jumbled volumes and the label-covered packing crate are the only objects in the piece. Art historian Andrew Walker has identified the titles of four books in the painting: Homer’s Odyssey, Cyclopaedia Americana/Vol. II, Arabian Nights, and Alexandre Dumas’s Forty-Five Guardsmen.

Most of the debate surrounding Harnett’s work centers around the issue of meaning. Nineteenth-century critics sometimes dismissed Harnett’s work as mere imitation lacking a message or narrative to give the image meaning. This attitude persisted into the twentieth century; the painter Marsden Hartley wrote that “there is no interpretation in Harnett, there is nothing to bother about, nothing to confuse, nothing to interpret, there are in the common sense no mind-workings—there is the myopic persistence to render every single thing, singly” (Hartley, Marsden. On Art by Marsden Hartley, ed. Gail R. Scott [New York: Horizon Press, 1982], pp. 178-79). Harnett’s biographer Alfred Frankenstein, the author of the first serious study of the artist’s work in the twentieth century, also dismissed any attempt to find meaning in Harnett’s art (quoted in Groseclose, Barbara S. “Vanity and the Artist: Some Still-Life Paintings by William Michael Harnett,” in American Art Journal 19, 1 (1987), p. 52).

Harnett, however, famously claimed in one of the few interviews he ever gave, “I endeavor to make the composition tell a story” (quoted in Bolger, Doreen, Marc Simpson, and John Wilmerding. William M. Harnett. Exh. cat. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1992, p. xv). This argument is supported by an essay by art historian Marc Simpson on Harnett’s inclusion of musical instruments and sheet music. Simpson notes that Harnett was himself a musician and an avid opera enthusiast. The inclusion of objects related to music, then, must have been meaningful to Harnett; he did not choose them simply for random or aesthetic reasons (Simpson, Marc. “Harnett and Music: Many a Touching Melody,” in Bolger, Doreen, Marc Simpson, and John Wilmerding. William M. Harnett. Exh. cat. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1992, p. 289).

Several art historians have attempted to puzzle out the meaning of the books in Job Lot Cheap. Charles Eldredge noted that three of the books represent a continent (Europe for The Odyssey, America for the encyclopedia, and Asia for Arabian Nights), and that the fact that only the encyclopedia is placed rightside up might indicate Harnett’s political allegiance to his native land (Eldredge, Charles C., Barbara Babcock Millhouse, and Robert G. Workman. American Originals: Selections from Reynolda House, Museum of American Art. New York: Abbeville Press, 1990, p. 84). Andrew Walker has suggested that Harnett was referencing the passage of time since, by 1878, this type of bookselling had been replaced by more modern commercial ventures such as department stores. Walker further points out that the purchaser of the painting, Byron Nugent, was the owner of a large and successful department store in Saint Louis, and thus might have appreciated this nostalgic look at the old ways of doing business.

Nostalgia also plays a role in Harnett’s most overtly vanitas pieces. Beginning in 1876 and ending in 1879, a period which includes the execution of Job Lot Cheap, Harnett did a series of paintings of books with vanitas elements such as skulls, hourglasses, and snuffed-out candles. Still life painting has long been associated with vanitas, the passage of time and the inevitability of death. Still life paintings for centuries have featured fruit and flowers that fade, skulls that remind the viewer of death, and candles with a wisp of smoke indicating the extinguished flame.

While art historian Barbara Groseclose has proposed that Harnett’s vanitas paintings evoke not only the brevity of life but also the futility of human attempts to surmount death with artistic and literary creations (Groseclose, Barbara S. “Vanity and the Artist: Some Still-Life Paintings by William Michael Harnett,” in American Art Journal 19, 1 (1987), pp. 51-59), the absence in Job Lot Cheap of traditional vanitas elements such as skulls and candles might suggest a more hopeful reading. Although it is true that both the books depicted and, by extension, Harnett’s own painting, are for sale, they will continue to live on even if sold off. Perhaps in this case, Harnett is using his painting to convey the permanence of the written word and the painted canvas—indeed, of all of man’s artistic endeavors.

ProvenanceByron Nugent (1842 – 1908), St. Louis MO [1]

Julian Nugent (born 1893), St. Louis MO and Colorado Springs, CO [2]

To 1966

William Middendorf II (born 1924) , New York NY [3]

1966

Kennedy Galleries, Inc. New York NY [4]

From 1966

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem NC [5]

Notes:

[1] Reynolda House cover sheet 1981, object file.

[2] See note 1.

[3] See note 1.

[4] Bill of sale, object file.

[5] See note 4.

Exhibition HistoryPeale House Galleries, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia PA (Lent by John Middendorf II)

1966

Two Illusionist Painters- Harnett, Peto

Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Philadelphia PA (1966)

Cat. No. 9

1970

The Reality Of Appearance: The Trompe l'Oeil Tradition In American Painting

National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. (3/21/1970-5/3/1970)

Whitney Museum, New York NY (5/18/1970-7/5/1970)

University Art Museum, Berkeley CA and California Palace of the Legion of Honor, San Francisco CA (7/15/1970-8/31/1970)

Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit MI (9/15/1970-10/31/1970)

Cat. No. 27

1971

Reynolda House American Paintings

Hirschl and Adler Galleries, Inc., New York NY (1/13/1971-1/31/1971)

Cat. No.19

For the Benefit of the Smith College Scholarship Fund

1980

Plane Truth: American Trompe L'oeil Painting

Katonah Gallery, Katonah NY (6/7/1980 - 7/20/1980)

Cat. No.22

1981-1982

Painters of the Humble Truth: Masterpieces of American Still Life

Philbrook Art Center, Tulsa OK (9/27/1981-11/1/1981)

Oakland Museum, Oakland CA (12/1981-1/1982)

Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore MD (3/1982-4/1982)

National Academy of Design Museum, New York NY (5/1982-7/1982)

1990-1992

American Originals, Selections From Reynolda House Museum Of American Art

The American Federation of Arts:

Center for the Fine Arts, Miami FL (9/22/1990-11/18/1990)

Palm Springs Desert Museum, Palm Springs CA (12/16/1990-2/10/1991)

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York NY (3/6/1991-5/11/1991)

Memphis Brooks Museum of Art, Memphis TN (6/2/1991-7/28/1991)

Amon Carter Museum of Western Art, Fort Worth TX (8/17/1991-10/20/1991)

Terra Museum of American Art, Chicago IL (11/17/1991-1/12/1992)

The Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, OK (3/1/1992-4/26/1992)

1992-1993

The Still Life Painting Of William M. Harnett

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York NY (3/14/1992-6/14/1992)

Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth TX (7/18/1992-10/18/1992)

Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, San Francisco CA (11/14/1992-2/14/1993)

National Gallery of Art, Washington DC (3/14/1993-6/13/1993)

2005

Vanguard Collecting: American Art At Reynolda House

Reynolda Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem NC (4/1/2005-8/21/2005)

2010 - 2011

Taxing Visions: Financial Episodes in Late Nineteenth-Century American Painting

Palmer Museum of Art (9/28/2010 - 12/19/2010)

The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens (1/29/2011 - 5/30/2011)

2017

Samuel F.B. Morse's Gallery of the Louvre and the Art of Invention

Reynolda House Museum of American Art (02/17/2017 - 06/04/2017)

Published ReferencesLubin, David. Picturing A Nation: Art And Social Change In Nineteenth- Century America New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994: 296.

Silverstein, Michael and Greg Urban. Natural Histories Of Discourse Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1996: illus. cover.

INSIGHTS: The Faculty Journal of Austin Seminary 116, no. 1 (Fall 2000): cover illus.

Richards, Marion K. College Teaching: The Examined Life of a Humanities Professor Vol 36/No 4 (Fall 1988): 135-139.

Dry Goods Economist November 1, 1892.

Frankenstein, A. After The Hunt (1953): 45, 46-48, 52, 110, 168.

Lassiter, Barbara B. Reynolda House American Paintings. Winston-Salem, NC: Reynolda House, Inc., 1971: 40, illus. 41.

Millhouse, Barbara B. and Robert Workman. American Originals New York: Abbeville Press Publishers, 1990: 82-5.

Hutson, Martha. “William M Harnett.” American Art Review v.5 no.1 (Summer 1992): 80-83.

Burgard, Timothy Anglin. Masterworks of American Painting at the de Young. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 2005.

Mazow, Leo and Kevin Murphy. Taxing Visions: Financial Episodes in Late Nineteenth-Century American Art. Pennsylvania State University Press, 2010.

Bolger, Doreen and Marc Simpson. William M. Harnett. Harry N Abrams, 1992, exhib. cat.

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Reynolda: Her Muses, Her Stories , with contributions by Martha R. Severens and David Park Curry (Winston-Salem, N.C.: Reynolda House Museum of American Art affiliated with Wake Forest University, 2017). pg. 30, 31, 41, 98, 99, 128, 194

Status

Not on viewCollections