Skip to main content

"I draw direct on giant stones which I have ways and means of handling. … I print ap[p]roximately 50 proofs of each stone and while the stone is easy to spoil and change, by expert handling the proofs can be made to vary or not and the limit is only that of practicality of desire. The great disadvantage is that all of the editions must be pulled of course before a new drawing can be made on the stone. I have six stones and can draw on both sides. The process is chemical and not mechanical as in etching and engraving. The principle being the opposition of grease and water. We draw with sticks of grease loaded with lamp black with greasy ink or wash in a special and rare limestone. The white parts are kept wet when inking for printing. And the stone is treated with light etch and gum Arabic to reduce the grease and keep it in place." [1]

An avid draftsman since childhood, Bellows appreciated the immediacy of drawing directly on the stone, as well as the opportunities lithography offered for experimentation and refinement. From 1917 until his death, he worked in the medium with varying degrees of intensity. For example, he often produced prints in the winter time, noting that lithography was “great work for night and dark days, of which there are too many here in New York in winter.” [2]

Bellows had multiple sources for the subjects of his lithographs—his memories, his city, his family, his friends, current events, scenes from the art or sporting worlds, and old drawings produced years before. Sometimes he took the subject of a painting and produced a lithograph; other times, he worked the subject from a lithograph into a painting.

The artist spent the summers of 1918 and 1919 in Middletown, Rhode Island. During his first Rhode Island summer, he attended a tennis tournament at the nearby Newport Casino, a pivotal event for the artist, as explained by Glenn Peck of Allison Galleries:

"By 1919 the competitive ranks of tennis had grown exponentially and over two hundred tournaments were sanctioned by the United States Lawn Tennis Association across the country. In anticipation of the 1919 Doubles Championships, held that year in mid-August at the Longwood Cricket Club in Boston, MA, the Newport Lawn Tennis Club staged an invitational tournament for the leading competitors in the sport. For a week legendary players such as Bill Johnston and Bill Tilden battled it out in five set matches on the spacious enclosed grass courtyard of the Newport Casino. George Bellows, who enjoyed playing the game in New York with fellow artists Eugene Speicher, Leon Kroll and William Glackens, was there for that week. He enjoyed not only watching some exciting tennis, but the throngs of people in elegant attire who were there at the club at the height of the social season." [3]

The tennis tournament appealed to Bellows as an artistic subject, and the following year he produced two tennis paintings in his New York studio: Tennis at Newport, 1919, Metropolitan Museum of Art, and The Tournament, 1919, private collection. Unlike his boxing pictures, which are remarkable for the vivid intensity of and singular focus on the action in the ring, Bellows’s tennis paintings are quiet and orderly compositions. In the painting Tennis at Newport, the scene is divided into five horizontal bands which are stacked on top of each other. Scholars have noted that the shadows do not always correspond logically to a single light source, suggesting that Bellows’s adherence to the theory of Dynamic Symmetry might explain this compositional quirk. [4]

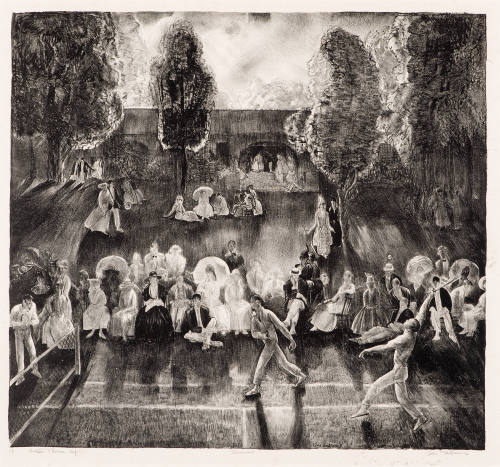

In March 1920, during the dark days of a New York winter, Bellows returned to the tennis subject in two lithographs, Tennis and The Tournament. These were the only lithographs he produced that year. Tennis, which is almost perfectly square in format, shares with the painting Tennis at Newport a composition of horizontal bands. Half of the court is evident in the immediate foreground, the lowest band, and a portion of the net is visible in the lower left corner. In the extreme lower left, on the other side of the net, stands a player holding a racket. On the opposite side, two players occupy half of the court. The figure in the center has just hit the ball, and it has been returned so that the player at right rears back to hit an overhand shot to the opposing team of doubles. Beyond the action, an orderly row of spectators observes the scene. They are finely dressed; many of the women carry parasols to shield themselves from the sun’s rays. While the players’ faces are rendered in some detail, the features of the seated spectators are indistinct and just barely suggested. Their forms cast long shadows on the court in front of them. Beyond them, couples stroll the club grounds, and groups of people sit and converse under the trees on the lawn. The elegant façade of the club building, designed by Charles McKim and Stanford White, is evident in the background, where more figures occupy the steps. [5] The top band above the building includes only sky and treetops. Bellows produced all of these forms with a quick and active line, varying the shades of light and dark with heavier or lighter applications of tusche wash.

Tennis is one of the first lithographs that Bellows printed after he shifted from George Miller as his printer to Bolton Brown. Brown worked closely with Bellows, even designing lithographic crayons specifically for the artist’s use. [6] Brown also signed all of the prints that he produced with Bellows, asserting the importance of their collaboration in the production of lithographs of the highest quality and artistic merit.

Notes:

[1] Bellows, quoted in Jane Myers and Linda Ayres, George Bellows: The Artist and His Lithographs (Fort Worth, TX: Amon Carter Museum, 1988), 15.

[2] Bellows, quoted in Myers and Ayres, George Bellows, 15.

[3] Glenn Peck, “Bellows and the Casino at Newport,” http://hvallison.com/ViewEssay.aspx?id=2

[4] Michael Quick, Jane Myers, Marianne Doezema, and Franklin Kelly, The Paintings of George Bellows (New York: Harry N. Abrams Publishers, 1992), 74.

[5] Peck, http://hvallison.com/ViewEssay.aspx?id=2

[6] Myers and Ayres, George Bellows, 74.

ProvenanceFrom 1977

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC, given by Stuart P. Feld sometime in 1977. [1]

Notes:

[1] Letter, May 11, 1998, Object File.

Exhibition History1976

Reynolda House, Museum of American Art Twentieth Century American Print Collection (Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC)(12/3/1976 - ?)

A selection of the Museum's prints were installed throughout the house. The checklist from the opening does not give a closing date for this display.

2021

The Voyage of Life: Art, Allegory, and Community Response

Reynolda House Museum of American Art (7/16/2021 - 12/12/2021)

Published ReferencesReynolda House Museum of American Art, Reynolda: Her Muses, Her Stories , with contributions by Martha R. Severens and David Park Curry (Winston-Salem, N.C.: Reynolda House Museum of American Art affiliated with Wake Forest University, 2017).

pd. 45, 150, 151

DepartmentAmerican Art

Tennis

Artist

George Wesley Bellows

(1882 - 1925)

Date1920

Mediumlithograph

DimensionsFrame: 28 3/4 x 29 3/4 in. (73 x 75.6 cm)

Image: 18 1/4 x 20 in. (46.4 x 50.8 cm)

SignedGeo Bellows

Credit LineGift of Stuart P. Feld

CopyrightPublic Domain

Object number1977.2.2

DescriptionIn 1917, shortly after he first began experimenting with the medium of lithography, George Bellows described his technique in a letter to a friend:"I draw direct on giant stones which I have ways and means of handling. … I print ap[p]roximately 50 proofs of each stone and while the stone is easy to spoil and change, by expert handling the proofs can be made to vary or not and the limit is only that of practicality of desire. The great disadvantage is that all of the editions must be pulled of course before a new drawing can be made on the stone. I have six stones and can draw on both sides. The process is chemical and not mechanical as in etching and engraving. The principle being the opposition of grease and water. We draw with sticks of grease loaded with lamp black with greasy ink or wash in a special and rare limestone. The white parts are kept wet when inking for printing. And the stone is treated with light etch and gum Arabic to reduce the grease and keep it in place." [1]

An avid draftsman since childhood, Bellows appreciated the immediacy of drawing directly on the stone, as well as the opportunities lithography offered for experimentation and refinement. From 1917 until his death, he worked in the medium with varying degrees of intensity. For example, he often produced prints in the winter time, noting that lithography was “great work for night and dark days, of which there are too many here in New York in winter.” [2]

Bellows had multiple sources for the subjects of his lithographs—his memories, his city, his family, his friends, current events, scenes from the art or sporting worlds, and old drawings produced years before. Sometimes he took the subject of a painting and produced a lithograph; other times, he worked the subject from a lithograph into a painting.

The artist spent the summers of 1918 and 1919 in Middletown, Rhode Island. During his first Rhode Island summer, he attended a tennis tournament at the nearby Newport Casino, a pivotal event for the artist, as explained by Glenn Peck of Allison Galleries:

"By 1919 the competitive ranks of tennis had grown exponentially and over two hundred tournaments were sanctioned by the United States Lawn Tennis Association across the country. In anticipation of the 1919 Doubles Championships, held that year in mid-August at the Longwood Cricket Club in Boston, MA, the Newport Lawn Tennis Club staged an invitational tournament for the leading competitors in the sport. For a week legendary players such as Bill Johnston and Bill Tilden battled it out in five set matches on the spacious enclosed grass courtyard of the Newport Casino. George Bellows, who enjoyed playing the game in New York with fellow artists Eugene Speicher, Leon Kroll and William Glackens, was there for that week. He enjoyed not only watching some exciting tennis, but the throngs of people in elegant attire who were there at the club at the height of the social season." [3]

The tennis tournament appealed to Bellows as an artistic subject, and the following year he produced two tennis paintings in his New York studio: Tennis at Newport, 1919, Metropolitan Museum of Art, and The Tournament, 1919, private collection. Unlike his boxing pictures, which are remarkable for the vivid intensity of and singular focus on the action in the ring, Bellows’s tennis paintings are quiet and orderly compositions. In the painting Tennis at Newport, the scene is divided into five horizontal bands which are stacked on top of each other. Scholars have noted that the shadows do not always correspond logically to a single light source, suggesting that Bellows’s adherence to the theory of Dynamic Symmetry might explain this compositional quirk. [4]

In March 1920, during the dark days of a New York winter, Bellows returned to the tennis subject in two lithographs, Tennis and The Tournament. These were the only lithographs he produced that year. Tennis, which is almost perfectly square in format, shares with the painting Tennis at Newport a composition of horizontal bands. Half of the court is evident in the immediate foreground, the lowest band, and a portion of the net is visible in the lower left corner. In the extreme lower left, on the other side of the net, stands a player holding a racket. On the opposite side, two players occupy half of the court. The figure in the center has just hit the ball, and it has been returned so that the player at right rears back to hit an overhand shot to the opposing team of doubles. Beyond the action, an orderly row of spectators observes the scene. They are finely dressed; many of the women carry parasols to shield themselves from the sun’s rays. While the players’ faces are rendered in some detail, the features of the seated spectators are indistinct and just barely suggested. Their forms cast long shadows on the court in front of them. Beyond them, couples stroll the club grounds, and groups of people sit and converse under the trees on the lawn. The elegant façade of the club building, designed by Charles McKim and Stanford White, is evident in the background, where more figures occupy the steps. [5] The top band above the building includes only sky and treetops. Bellows produced all of these forms with a quick and active line, varying the shades of light and dark with heavier or lighter applications of tusche wash.

Tennis is one of the first lithographs that Bellows printed after he shifted from George Miller as his printer to Bolton Brown. Brown worked closely with Bellows, even designing lithographic crayons specifically for the artist’s use. [6] Brown also signed all of the prints that he produced with Bellows, asserting the importance of their collaboration in the production of lithographs of the highest quality and artistic merit.

Notes:

[1] Bellows, quoted in Jane Myers and Linda Ayres, George Bellows: The Artist and His Lithographs (Fort Worth, TX: Amon Carter Museum, 1988), 15.

[2] Bellows, quoted in Myers and Ayres, George Bellows, 15.

[3] Glenn Peck, “Bellows and the Casino at Newport,” http://hvallison.com/ViewEssay.aspx?id=2

[4] Michael Quick, Jane Myers, Marianne Doezema, and Franklin Kelly, The Paintings of George Bellows (New York: Harry N. Abrams Publishers, 1992), 74.

[5] Peck, http://hvallison.com/ViewEssay.aspx?id=2

[6] Myers and Ayres, George Bellows, 74.

ProvenanceFrom 1977

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC, given by Stuart P. Feld sometime in 1977. [1]

Notes:

[1] Letter, May 11, 1998, Object File.

Exhibition History1976

Reynolda House, Museum of American Art Twentieth Century American Print Collection (Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC)(12/3/1976 - ?)

A selection of the Museum's prints were installed throughout the house. The checklist from the opening does not give a closing date for this display.

2021

The Voyage of Life: Art, Allegory, and Community Response

Reynolda House Museum of American Art (7/16/2021 - 12/12/2021)

Published ReferencesReynolda House Museum of American Art, Reynolda: Her Muses, Her Stories , with contributions by Martha R. Severens and David Park Curry (Winston-Salem, N.C.: Reynolda House Museum of American Art affiliated with Wake Forest University, 2017).

pd. 45, 150, 151

Status

Not on view