Alan J. Shields

Alan Shields (1944–2005) made a remarkably quick transition from the obscurity of his native Midwest to artistic success in the New York City art world of the late 1960s and 1970s. Like many artists of that era, he explored unconventional uses of materials, pushing the limits of art-making while, at the same time, employing such traditional techniques as sewing and beading.

Shields was born on a farm in Herington, Kansas, and took courses in civil engineering and studio art at Kansas State University, but did not graduate. In 1968 and 1969, he studied theater at the University of Maine Summer Workshop. He moved to New York in 1968 and took a job at Max’s Kansas City bar, a favorite gathering place for members of the downtown art scene. He managed to meet artists there whom he had only read about in ArtNews. In his off hours he scouted new work being shown in the galleries and made his own works, sewing and stitching his canvases. Before long his friend, sculptor Mark di Suvero, introduced Shields to his dealer Paula Cooper, who gave him a one-man show at her gallery in 1969. Four years later he received a Guggenheim fellowship. After the height of his fame during the pluralistic 1970s, Shields received steadily waning critical attention for his art due to both his decision to move out of New York City to Shelter Island and to shifting tastes in the art world.

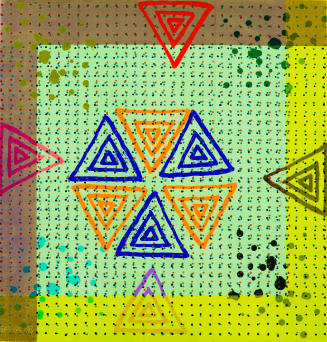

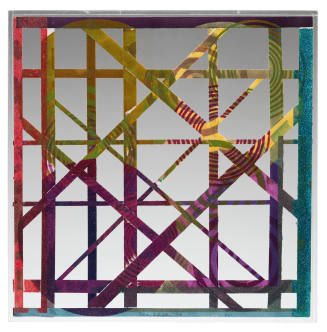

The two major modernist trends that followed Abstract Expressionism and Pop were Minimalism, which emphasized the physicality of the art object, and Conceptualism, where the idea of art took precedence over producing an art object. Stylistically, Shields was post-Minimalist and pre-Pattern & Decoration and, as an artist, very much his own person. While his art may no longer seem radical, the work retains its chaotic, colorful, playful, unkempt, and unorthodox character. His large mixed-media installations incorporated both painted and sculptural elements such as found objects and items of Shields’s own fabrication. The latter would often incorporate sewing, beading, weaving, and dyeing techniques. The allover openness and indeterminate nature of his works allow the viewer to perceive them from multiple points of view, especially his double-sided works. Two years after his death, art critic Benjamin Genocchio categorized Shields’s art as Deconstruction: “working with the same materials and tools used to make conventional paintings but producing art that in no way resembled them.” As such, these artworks present a novel concept of materiality that is derived from its atypical or unexpected use. [1]

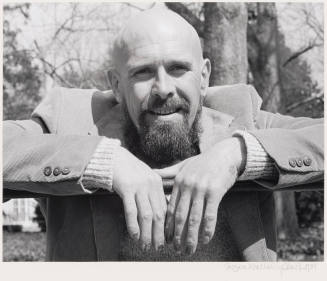

Alan Shields’s love of ornament and design manifested itself in his personal appearance and his singular unconcern with gender conventionality. He was well over six feet tall and shaved his head, wore an earring, had several tattoos, and painted his fingernails. Growing up, he had seen his mother and sisters sew; eventually Shields too turned to the sewing machine when he wanted to produce large paintings that could be shipped easily and safely. He had started to use a sewing machine in his art classes during college and would stitch directly on canvas or paper. This sewing technique resulted in works with two distinct sides, both of which were equally interesting to the artist. He incorporated a formalist grid in almost all his prints and paintings but this structure did not inhibit his elaborate and complicated investigation of materials and spatial dimension.

In 1972, Shields bought a house and built a studio in Eel Town on New York’s Shelter Island. He moved there full time a decade later, deriving great satisfaction from fishing, gardening, and using materials and resources close at hand for his daily living and art-making needs. Despite his isolated situation, Shields thrived as a communal printmaker, working first with Bill Weege at his Jones Road Print Shop and Stable in Barneveld, Wisconsin, in the early 1970s, then with Ken Tyler at Tyler Graphics, Ltd., in Bedford Village, New York. Shields also travelled to India to produce handmade paper at the Gandhi Ashram paper mill in Ahmadabad. Although his death in 2005 received little notice in the national art press, a few critics find Shields’s artistic legacy evident in the work of such 21st century artists as Jessica Stockholder, Jim Lambie, and Jim Isermann.

[1] Benjamin Genocchio, “Deconstruction Zone,” The New York Times (Long Island Edition), November 11, 2007, 12.