Skip to main content

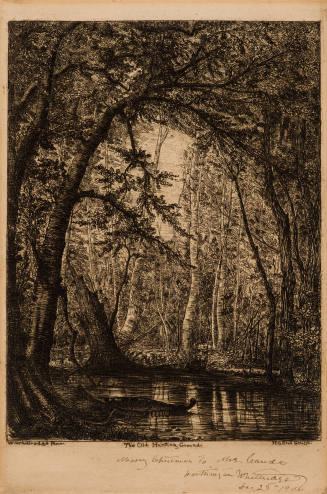

The composition is dominated by a grove of illuminated birches that comprises the focal point of the canvas. Their vertical arrangement and stark white bark draw the viewer into the scene. A pattern of falling limbs creates a diagonal path across the composition and helps to define the illusion of space. A broken and rotted trunk leans at a dramatic angle in the left mid-ground. Its position beneath a larger leaning tree creates the impression that it holds up the weight of its living counterpart. The dark branches of this unstable arbor arch across the top third of the painting. These sweeping forms push the white birch back into space and create an architectural frame that echoes a Gothic cathedral. Yet, access to the structured space is denied through the foregrounding of the stagnant pool and decaying canoe. This is not a landscape to be entered into nor is it a space which can be easily traversed.

Whittredge painted three versions of The Old Hunting Grounds during his career. Reynolda House’s is the original painting and is the best known of the three; it was shown at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1867 where it served as a representative of American painting, and again at the Centennial exhibition in Philadelphia in 1876. Although there is no mention of the painting in period exhibition reviews, it was singled out by Whittredge’s peers as emblematic of the painter’s skill at evoking poetic tenderness through accurate rendering. [1] Over the years the title has varied; occasionally “ground” appears as singular, but the artist himself referred to it in the plural: “The names of some of my pictures, however may serve to give an idea of the different subjects I have undertaken…in America, ‘The Old Hunting Grounds’ (Catskill Mountains).” [2]

Reynolda House’s canvas was purchased the year it was painted by James Pinchot, a wealthy importer and manufacturer of wallpaper, whose family had engaged in land speculation and timbering. Distressed by the waste of natural resources, especially forests, he became a strong advocate for conservation and careful land management, and earned the moniker “Father of American Forestry.” Pinchot was a cultivated individual and patron who counted among his friends William Cullen Bryant, Sanford Gifford, Eastman Johnson, and Whittredge, who frequently visited him at his estate, Grey Towers, in Milford, Pennsylvania. Given his friendship with the artist and interest in forestry, The Old Hunting Grounds was a logical acquisition.

In his Book of the Artists, Henry Tuckerman reveals the allegorical power of the painting: “Whittredge's Old Hunting Ground has been well called an idyl, [sic] telling its story in the deserted, broken canoe, the shallow bit of water wherein a deer stoops to drink, and the melancholy silvery birches that bend under the weight of years, and lean towards each other as though breathing of the light of other days ere the red man sought other grounds, and left them to sough and sigh in solitude.” [3] In this passage, Tuckerman emphasizes the picturesque appeal that the melancholy narrative of lost Native American culture held for his contemporaries who would have seen the decaying birch canoe as emblematic of the passing of tribal peoples. Through the evocation of this narrative within such an intimate landscape, Whittredge is able to merge the allegorical appeal of Thomas Cole with Asher B. Durand’s emphasis on careful and accurate observation.

The implied loss of native cultures places this image within a broader context of literary production and political actions unfolding in mid-century America. The Indian Removal Act of 1830 actively pushed native peoples west, resulting in the deaths of thousands. Sympathizers feared that the culture of Native Americans would be lost forever. This anxiety was manifest in popular fiction and poetry; The Old Hunting Grounds has specifically been linked to the poetry of Bryant whose nostalgic sentiments elevate the loss of the noble “red man” who once dwelled in the American forests. [4] Two years later, in 1866, while on an expedition to the west, Whittredge’s view of Native Americans differed: “At the time the Indians were none too civil; the tribe abounding in the region were the Utes. We seldom saw any of them, but an Indian can hide where a white man cannot, and we had met all along our route plenty of ghastly evidences of murders, burning of ranches, and stealings innumerable, until I had frequently been ordered to come back to camp when the General (Pope) saw my white umbrella perched on an eminence in one of the most innocent looking landscapes on earth, and not an Indian having been seen for days.” [5]

Ultimately, The Old Hunting Grounds maintains a balance between life and death that has not been broken, but is in jeopardy. Whittredge creates a seemingly benign environment through familiar landscape devices that work to conceal the underlying anxiety present in the scene. Throughout the century, landscape painting was the highest form of cultural expression. Yet, conceptions of nature experienced radical shifts. Artists like Whittredge found ways to navigate the tensions and anxieties posed by political events, and shifting conceptions of national identity.

Notes:

[1] Anthony F. Janson, Worthington Whittredge (Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1989), 81; National Academy of Design, The American Art Journal, 5, no. 2 (May 2, 1866), 20, and “American Painters. Worthington Whittredge,” The Art Journal, New Series, 2 (1876), 148–149.

[2] Janson, Worthington Whittredge refers to it in the singular, but it is plural in Charles C. Eldredge, Barbara Babcock Millhouse, and Robert G. Workman, American Originals: Selections from Reynolda House, Museum of American Art (New York: Abbeville Press, 1990), 62. Whittredge, “The Autobiography of Worthington Whittredge 1820–1910,” John I. H. Baur, ed., reprint Brooklyn Museum Journal, 1942, 63.

[3] Henry Tuckerman, Book of the Artists, American Artist Life (New York: G.P. Putnam and Son, 1867), 518.

[4] See for example James Fenimore Cooper’s Last of the Mohicans, 1826, and Janson, Worthington Whittredge, 84.

[5] Whittredge, “The Autobiography,” 46.

ProvenanceFrom 1864 to 1908

James W. Pinchot (1831-1908), purchased at the National Academy of Design, New York when on display in 1864. [1]

From 1908 to 1946

Gifford Pinchot (1865-1946), Milford PA, bequest by James W. Pinchot in February 1908. [2]

From 1946 to 1960s

Gifford B. Pinchot, M.D. (1915-1989), bequest by Gifford Pinchot in 1946. [3]

c. 1967

Mitchell Work Gallery, New Jersey, purchased from antique dealer in the New York countryside. [4]

From 1967 to 1976

Barbara B. Millhouse, New York, purchased from Mitchell Work, New Jersey in 1967. [5]

From 1976

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, gift of Barbara B. Millhouse on December 17, 1976. [6]

Notes:

[1] Letter from Mitchell Work April 9, 1967.

[2] See note 1. Also Letter from Gifford B. Pinchot M.D. on May 23, 1969.

[3] See note 2.

[4] See note 1. Also phone note record from Barbara Millhouse files.

[5] See note 4.

[6] Deed of Gift, Object file.

Exhibition History1867

Exposition Universelle of 1867

Paris, France (1867)

Cat. No. 73

Lent by J.W. Pinchot, as "La terre de vieux Kentucky."

1876

International Centennial Exhibition of 1876

United States Centennial Commission, Philadelphia PA (1876)

Cat. No. 119

Lent by J.W. Pinchot.

1878

Loan Exhibition to Aid the Society of Decorative Art

National Academy of Design, New York NY(1878)

Lent by J.W. Pinchot.

1880-1881

Loan Collection of Paintings

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York NY (1880-1881)

Cat. No. 194

Lent by J.W. Pinchot.

1968

The American Vision

Paul Rosenburg and Co., New York NY (1968)

Cat. No. 107

For the benefit of the Public Education Association.

1969-1970

Worthington Whittredge (1820-1910): A Retrospective Exhibition of an American Artist

Munson-Williams-Proctor Institute, Utica NY (10/5/1969-11/16/1969)

Albany Institute of History and Art, Albany NY (12/2/1969-1/19/1970)

Cincinnati Art Museum, Cincinnati OH (2/6/1970-3/8/1970)

Cat. No. 11

1971

Reynolda House Paintings

Hirschl and Adler Galleries, New York NY (1/13/1971-1/31/1971)

Cat. No. 13

1976

The Natural Paradise: Painting in America 1800-1850 T

The Museum of Modern Art, New York NY (10/1/1976-11/30/1976)

1980

A Mirror of Creation: 150 Years of American Nature Painting

The Vatican Museums, Braccio di Carlo Magno (1980)

Cat. No. 5

1980-1981

A Mirror of Creation: 150 Years of American Nature Painting

Terra Museum of American Art, Evanston IL (12/20/1980-3/15/1981)

1987-1988

The Hudson River School of American Landscape Painting

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York NY (9/22/1987-1/3/1988)

1990-1992

American Originals, Selections From Reynolda House Museum Of American Art

The American Federation of Arts

Center for the Fine Arts, Miami FL (9/22/1990-11/18/1990)

Palm Springs Desert Museum, Palm Springs CA (12/16/1990-2/10/1991)

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York NY (3/6/1991-5/11/1991)

Memphis Brooks Museum of Art, Memphis TN (6/2/1991-7/28/1991)

Amon Carter Museum of Western Art, Fort Worth TX (8/17/1991-10/20/1991)

Terra Museum of American Art, Chicago IL (11/17/1991-1/12/1992)

The Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, OK (3/1/1992-4/26/1992)

Cat. No. 16 (bk.)

2005

Vanguard Collecting: American Art at Reynolda House

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem NC (4/1/2005-8/21/2005)

2017

Samuel F.B. Morse's Gallery of the Louvre and the Art of Invention

Reynolda House Museum of American Art (02/17/2017 - 06/04/2017)

Published References"American Painters:--Worthington Whittredge, N.A." The Art Journal, N.S. (American Edition) 1876: II, 350.

Clement, Clara Erskine & Laurence Hutton.Artists Of The Nineteenth Century And Their Works. Boston: Houghton, Osgood & Co., 1879: 350.

Sheldon, G.W. American Painters. New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1879: 100.

Champlin, John Denison Jr. & Charles C. Perkins (ed.). Cyclopedia Of Painters And Paintings. IV New York: Charles Scribners Sons, 1888: 428.

Wilson, James Grant & John Fiske (ed.). Appleton's Cyclopaedia Of American Biography VI New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1889: 497.

Baur, John I.H. (ed.) "Autobigoraphy of Worthington Whittredge 1820-1910." The Brooklyn Museum Journal 1942: 62-3.

Dwight, E.H. "Worthington Whittredge, Artist of the Hudson River School" ANTIQUES XCVI (October 1969): illus. 585.

Lassiter, Barbara B. Reynolda House American Paintings. Winston-Salem, NC: Reynolda House, Inc., 1971: 28, illus. 29.

Millhouse, Barbara B. and Robert Workman. American Originals New York: Abbeville Press Pub., 1990: 62-5.

Favis, Roberta Smith. "Home Again: Worthington Whittredge's Domestic Interiors." American Art 9:1, 23.

Schama, Simon. Landscape and Memory. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. 1994.

Keener, William G. "The Education of a Painter: Thomas Worthington Whittredge." Timeline 12 (May/June 1995) Columbus, OH: Ohio Historical Society: no. 3, 34-49.

Yaeger, Bert. The Hudson River School: American Landscape Artists NY: SmithMark Publishers, 1996.

Living In Our World: The Americas Raleigh, NC: Humanities Extension/Publications Program North Carolina State University, 1998: illus. 124.

The American Art Book. London: Phaidon Press, Inc., 1999: 486, illus. 486.

Stebbins, Theodore E. Jr., Comey, Janet L., Quinn, Karen E. & Wright, Jim. Martin Johnson Heade New Haven & London: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston in assoc. with Yale University Press.

The Encyclopedia Of American Art Before 1914 London: Macmillan: 631.

Tuckerman, Henry T. Book of the Artists. American Artist Life, Comprising Biographical and Critical Sketches of American Artists: Preceded by an Historical Account of the Rise and Progress of Art in America. New York: G. P. Putnam & Sons, 1867.

Reader’s Digest. (November 1988).

Georgia O’Keeffe visions of the sublime / edited by Joseph S. Czestochowski. Memphis: Torch Press and International Arts, 2004.

Cash, Sarah. Corcoran Gallery of Art Pre-1945 American Paintings Collection Catalogue. CGA and Marquand Books, Apr. 2011:138.

Simblet, Sarah. Botany for the Artist. New York: Dorling Kindersley, 2010.

Perse, Marcell. Natur im Blick: die Landschaften des Johann Wilhelm Schirmer. Jülich: Stadtgeschichtliches Museum und Forschungzentrum, 2001. ISBN: 3934176054.

Kindred Spirits: Asher B. Durand and the American Landscape. Ed. Linda S. Ferber. New York: Brooklyn Museum, 2007. ISBN: 1904832261.

Burgard, Timothy Anglin and Alfred C. Harrison Jr. California Impressions: Landscapes from the Wendy Willrich Collection. San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 2006. ISBN: 0884011259.

Severance, Carol. “The American Collection of James W. Pinchot (1831-1908).” Cooperstown Graduate Programs, HM598, Fall 1993. Dissertation.

Chibbaro, Julie. Redemption. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2004, cover image on a fiction book.

American Wilderness: The Rustic in Arts and Architecture, AFA, AFA in house, 4/2005. ?? not sure.

Crewdson, Gregory. Essay by Alexander Nemerov. Cathedral of the Pines. New York: Aperture, 2016, pg. iii.

Kusserow, Karl and Alan Braddock. Nature's Nation: American Art and the Environment. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018. pg. 98.

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Reynolda: Her Muses, Her Stories , with contributions by Martha R. Severens and David Park Curry (Winston-Salem, N.C.: Reynolda House Museum of American Art affiliated with Wake Forest University, 2017). pg. 60, 61-62, 148, 149

DepartmentAmerican Art

The Old Hunting Grounds

Artist

Worthington Whittredge

(1820 - 1910)

Date1864

Mediumoil on canvas

DimensionsFrame: 50 1/2 x 41 1/4 x 5 in. (128.3 x 104.8 x 12.7 cm)

Canvas: 36 1/4 x 27 1/8 in. (92.1 x 68.9 cm)

SignedW. Whittredge

Credit LineGift of Barbara B. Millhouse

CopyrightPublic Domain

Object number1976.2.10

DescriptionThis intimate landscape, considered by many Worthington Whittredge’s masterpiece, commands the attention of the viewer through dramatic use of light and a strong vertical composition. A limited palette, controlled brushstroke, and realistic forms create a picture of restrained natural beauty. However, the idyllic scene is disrupted by visual cues that describe a picturesque paradox between divinity and decay, allegory and exactitude. The composition is dominated by a grove of illuminated birches that comprises the focal point of the canvas. Their vertical arrangement and stark white bark draw the viewer into the scene. A pattern of falling limbs creates a diagonal path across the composition and helps to define the illusion of space. A broken and rotted trunk leans at a dramatic angle in the left mid-ground. Its position beneath a larger leaning tree creates the impression that it holds up the weight of its living counterpart. The dark branches of this unstable arbor arch across the top third of the painting. These sweeping forms push the white birch back into space and create an architectural frame that echoes a Gothic cathedral. Yet, access to the structured space is denied through the foregrounding of the stagnant pool and decaying canoe. This is not a landscape to be entered into nor is it a space which can be easily traversed.

Whittredge painted three versions of The Old Hunting Grounds during his career. Reynolda House’s is the original painting and is the best known of the three; it was shown at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1867 where it served as a representative of American painting, and again at the Centennial exhibition in Philadelphia in 1876. Although there is no mention of the painting in period exhibition reviews, it was singled out by Whittredge’s peers as emblematic of the painter’s skill at evoking poetic tenderness through accurate rendering. [1] Over the years the title has varied; occasionally “ground” appears as singular, but the artist himself referred to it in the plural: “The names of some of my pictures, however may serve to give an idea of the different subjects I have undertaken…in America, ‘The Old Hunting Grounds’ (Catskill Mountains).” [2]

Reynolda House’s canvas was purchased the year it was painted by James Pinchot, a wealthy importer and manufacturer of wallpaper, whose family had engaged in land speculation and timbering. Distressed by the waste of natural resources, especially forests, he became a strong advocate for conservation and careful land management, and earned the moniker “Father of American Forestry.” Pinchot was a cultivated individual and patron who counted among his friends William Cullen Bryant, Sanford Gifford, Eastman Johnson, and Whittredge, who frequently visited him at his estate, Grey Towers, in Milford, Pennsylvania. Given his friendship with the artist and interest in forestry, The Old Hunting Grounds was a logical acquisition.

In his Book of the Artists, Henry Tuckerman reveals the allegorical power of the painting: “Whittredge's Old Hunting Ground has been well called an idyl, [sic] telling its story in the deserted, broken canoe, the shallow bit of water wherein a deer stoops to drink, and the melancholy silvery birches that bend under the weight of years, and lean towards each other as though breathing of the light of other days ere the red man sought other grounds, and left them to sough and sigh in solitude.” [3] In this passage, Tuckerman emphasizes the picturesque appeal that the melancholy narrative of lost Native American culture held for his contemporaries who would have seen the decaying birch canoe as emblematic of the passing of tribal peoples. Through the evocation of this narrative within such an intimate landscape, Whittredge is able to merge the allegorical appeal of Thomas Cole with Asher B. Durand’s emphasis on careful and accurate observation.

The implied loss of native cultures places this image within a broader context of literary production and political actions unfolding in mid-century America. The Indian Removal Act of 1830 actively pushed native peoples west, resulting in the deaths of thousands. Sympathizers feared that the culture of Native Americans would be lost forever. This anxiety was manifest in popular fiction and poetry; The Old Hunting Grounds has specifically been linked to the poetry of Bryant whose nostalgic sentiments elevate the loss of the noble “red man” who once dwelled in the American forests. [4] Two years later, in 1866, while on an expedition to the west, Whittredge’s view of Native Americans differed: “At the time the Indians were none too civil; the tribe abounding in the region were the Utes. We seldom saw any of them, but an Indian can hide where a white man cannot, and we had met all along our route plenty of ghastly evidences of murders, burning of ranches, and stealings innumerable, until I had frequently been ordered to come back to camp when the General (Pope) saw my white umbrella perched on an eminence in one of the most innocent looking landscapes on earth, and not an Indian having been seen for days.” [5]

Ultimately, The Old Hunting Grounds maintains a balance between life and death that has not been broken, but is in jeopardy. Whittredge creates a seemingly benign environment through familiar landscape devices that work to conceal the underlying anxiety present in the scene. Throughout the century, landscape painting was the highest form of cultural expression. Yet, conceptions of nature experienced radical shifts. Artists like Whittredge found ways to navigate the tensions and anxieties posed by political events, and shifting conceptions of national identity.

Notes:

[1] Anthony F. Janson, Worthington Whittredge (Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1989), 81; National Academy of Design, The American Art Journal, 5, no. 2 (May 2, 1866), 20, and “American Painters. Worthington Whittredge,” The Art Journal, New Series, 2 (1876), 148–149.

[2] Janson, Worthington Whittredge refers to it in the singular, but it is plural in Charles C. Eldredge, Barbara Babcock Millhouse, and Robert G. Workman, American Originals: Selections from Reynolda House, Museum of American Art (New York: Abbeville Press, 1990), 62. Whittredge, “The Autobiography of Worthington Whittredge 1820–1910,” John I. H. Baur, ed., reprint Brooklyn Museum Journal, 1942, 63.

[3] Henry Tuckerman, Book of the Artists, American Artist Life (New York: G.P. Putnam and Son, 1867), 518.

[4] See for example James Fenimore Cooper’s Last of the Mohicans, 1826, and Janson, Worthington Whittredge, 84.

[5] Whittredge, “The Autobiography,” 46.

ProvenanceFrom 1864 to 1908

James W. Pinchot (1831-1908), purchased at the National Academy of Design, New York when on display in 1864. [1]

From 1908 to 1946

Gifford Pinchot (1865-1946), Milford PA, bequest by James W. Pinchot in February 1908. [2]

From 1946 to 1960s

Gifford B. Pinchot, M.D. (1915-1989), bequest by Gifford Pinchot in 1946. [3]

c. 1967

Mitchell Work Gallery, New Jersey, purchased from antique dealer in the New York countryside. [4]

From 1967 to 1976

Barbara B. Millhouse, New York, purchased from Mitchell Work, New Jersey in 1967. [5]

From 1976

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, gift of Barbara B. Millhouse on December 17, 1976. [6]

Notes:

[1] Letter from Mitchell Work April 9, 1967.

[2] See note 1. Also Letter from Gifford B. Pinchot M.D. on May 23, 1969.

[3] See note 2.

[4] See note 1. Also phone note record from Barbara Millhouse files.

[5] See note 4.

[6] Deed of Gift, Object file.

Exhibition History1867

Exposition Universelle of 1867

Paris, France (1867)

Cat. No. 73

Lent by J.W. Pinchot, as "La terre de vieux Kentucky."

1876

International Centennial Exhibition of 1876

United States Centennial Commission, Philadelphia PA (1876)

Cat. No. 119

Lent by J.W. Pinchot.

1878

Loan Exhibition to Aid the Society of Decorative Art

National Academy of Design, New York NY(1878)

Lent by J.W. Pinchot.

1880-1881

Loan Collection of Paintings

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York NY (1880-1881)

Cat. No. 194

Lent by J.W. Pinchot.

1968

The American Vision

Paul Rosenburg and Co., New York NY (1968)

Cat. No. 107

For the benefit of the Public Education Association.

1969-1970

Worthington Whittredge (1820-1910): A Retrospective Exhibition of an American Artist

Munson-Williams-Proctor Institute, Utica NY (10/5/1969-11/16/1969)

Albany Institute of History and Art, Albany NY (12/2/1969-1/19/1970)

Cincinnati Art Museum, Cincinnati OH (2/6/1970-3/8/1970)

Cat. No. 11

1971

Reynolda House Paintings

Hirschl and Adler Galleries, New York NY (1/13/1971-1/31/1971)

Cat. No. 13

1976

The Natural Paradise: Painting in America 1800-1850 T

The Museum of Modern Art, New York NY (10/1/1976-11/30/1976)

1980

A Mirror of Creation: 150 Years of American Nature Painting

The Vatican Museums, Braccio di Carlo Magno (1980)

Cat. No. 5

1980-1981

A Mirror of Creation: 150 Years of American Nature Painting

Terra Museum of American Art, Evanston IL (12/20/1980-3/15/1981)

1987-1988

The Hudson River School of American Landscape Painting

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York NY (9/22/1987-1/3/1988)

1990-1992

American Originals, Selections From Reynolda House Museum Of American Art

The American Federation of Arts

Center for the Fine Arts, Miami FL (9/22/1990-11/18/1990)

Palm Springs Desert Museum, Palm Springs CA (12/16/1990-2/10/1991)

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York NY (3/6/1991-5/11/1991)

Memphis Brooks Museum of Art, Memphis TN (6/2/1991-7/28/1991)

Amon Carter Museum of Western Art, Fort Worth TX (8/17/1991-10/20/1991)

Terra Museum of American Art, Chicago IL (11/17/1991-1/12/1992)

The Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, OK (3/1/1992-4/26/1992)

Cat. No. 16 (bk.)

2005

Vanguard Collecting: American Art at Reynolda House

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem NC (4/1/2005-8/21/2005)

2017

Samuel F.B. Morse's Gallery of the Louvre and the Art of Invention

Reynolda House Museum of American Art (02/17/2017 - 06/04/2017)

Published References"American Painters:--Worthington Whittredge, N.A." The Art Journal, N.S. (American Edition) 1876: II, 350.

Clement, Clara Erskine & Laurence Hutton.Artists Of The Nineteenth Century And Their Works. Boston: Houghton, Osgood & Co., 1879: 350.

Sheldon, G.W. American Painters. New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1879: 100.

Champlin, John Denison Jr. & Charles C. Perkins (ed.). Cyclopedia Of Painters And Paintings. IV New York: Charles Scribners Sons, 1888: 428.

Wilson, James Grant & John Fiske (ed.). Appleton's Cyclopaedia Of American Biography VI New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1889: 497.

Baur, John I.H. (ed.) "Autobigoraphy of Worthington Whittredge 1820-1910." The Brooklyn Museum Journal 1942: 62-3.

Dwight, E.H. "Worthington Whittredge, Artist of the Hudson River School" ANTIQUES XCVI (October 1969): illus. 585.

Lassiter, Barbara B. Reynolda House American Paintings. Winston-Salem, NC: Reynolda House, Inc., 1971: 28, illus. 29.

Millhouse, Barbara B. and Robert Workman. American Originals New York: Abbeville Press Pub., 1990: 62-5.

Favis, Roberta Smith. "Home Again: Worthington Whittredge's Domestic Interiors." American Art 9:1, 23.

Schama, Simon. Landscape and Memory. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. 1994.

Keener, William G. "The Education of a Painter: Thomas Worthington Whittredge." Timeline 12 (May/June 1995) Columbus, OH: Ohio Historical Society: no. 3, 34-49.

Yaeger, Bert. The Hudson River School: American Landscape Artists NY: SmithMark Publishers, 1996.

Living In Our World: The Americas Raleigh, NC: Humanities Extension/Publications Program North Carolina State University, 1998: illus. 124.

The American Art Book. London: Phaidon Press, Inc., 1999: 486, illus. 486.

Stebbins, Theodore E. Jr., Comey, Janet L., Quinn, Karen E. & Wright, Jim. Martin Johnson Heade New Haven & London: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston in assoc. with Yale University Press.

The Encyclopedia Of American Art Before 1914 London: Macmillan: 631.

Tuckerman, Henry T. Book of the Artists. American Artist Life, Comprising Biographical and Critical Sketches of American Artists: Preceded by an Historical Account of the Rise and Progress of Art in America. New York: G. P. Putnam & Sons, 1867.

Reader’s Digest. (November 1988).

Georgia O’Keeffe visions of the sublime / edited by Joseph S. Czestochowski. Memphis: Torch Press and International Arts, 2004.

Cash, Sarah. Corcoran Gallery of Art Pre-1945 American Paintings Collection Catalogue. CGA and Marquand Books, Apr. 2011:138.

Simblet, Sarah. Botany for the Artist. New York: Dorling Kindersley, 2010.

Perse, Marcell. Natur im Blick: die Landschaften des Johann Wilhelm Schirmer. Jülich: Stadtgeschichtliches Museum und Forschungzentrum, 2001. ISBN: 3934176054.

Kindred Spirits: Asher B. Durand and the American Landscape. Ed. Linda S. Ferber. New York: Brooklyn Museum, 2007. ISBN: 1904832261.

Burgard, Timothy Anglin and Alfred C. Harrison Jr. California Impressions: Landscapes from the Wendy Willrich Collection. San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 2006. ISBN: 0884011259.

Severance, Carol. “The American Collection of James W. Pinchot (1831-1908).” Cooperstown Graduate Programs, HM598, Fall 1993. Dissertation.

Chibbaro, Julie. Redemption. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2004, cover image on a fiction book.

American Wilderness: The Rustic in Arts and Architecture, AFA, AFA in house, 4/2005. ?? not sure.

Crewdson, Gregory. Essay by Alexander Nemerov. Cathedral of the Pines. New York: Aperture, 2016, pg. iii.

Kusserow, Karl and Alan Braddock. Nature's Nation: American Art and the Environment. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018. pg. 98.

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Reynolda: Her Muses, Her Stories , with contributions by Martha R. Severens and David Park Curry (Winston-Salem, N.C.: Reynolda House Museum of American Art affiliated with Wake Forest University, 2017). pg. 60, 61-62, 148, 149

Status

On view