Skip to main content

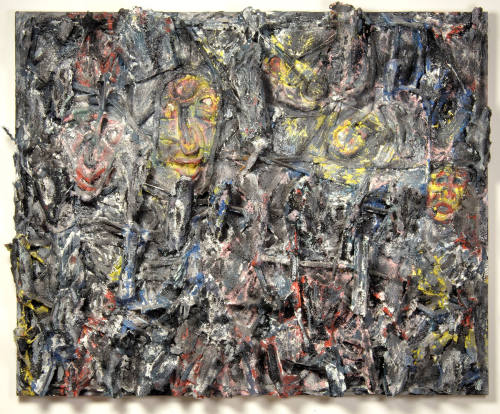

The imagery of the visually active and tactile composition is masked by a mottled gray surface. The implicit and actual weight of the materials Dial has affixed to the canvas-covered plywood base project so far from the support that one supposes that parts might just fall off. The work is held together by a seemingly continuous length of roping, anchored to the support by large strong knots and sealant. Pinks, red, blue, and yellow paint are flecked over specific surface areas of the composition. Examined more intently, but at some distance, these colors highlight rope outlines of human figures and a stylized tiger. The work is signed T.D. just above the tiger, in the upper right corner.

Crying in the Jungle, Crying for Jobs is a heroic piece, created in the same year as the 1996 Summer Olympic Games in Atlanta, Georgia. Dial had a one-man exhibition at the Michael C. Carlos Museum at Emory University in Atlanta and was included in a group show as part of the cultural festivities. However, this artwork does not directly address global sports. It relates to Dial’s Tragedies period, almost certainly referencing the fallout from the disastrous Sixty Minutes television episode in 1993 when Morley Safer questioned the motivations of Dial’s patron William Arnett. Dial’s subsequent works do not have the overall vibrancy of earlier works, although they have more gravitas. [2]

In an assessment of the work, gallerist Frank Maresca offered the following interpretation: “The painting presents members of a white and African American oligarchy, who are painted from left to right in pink and in a light yellow pigment. In the upper right, just beyond center, Dial has inserted his signature tiger cat as a bruised creature, who emits light in the ghetto/jungle below. Also in the upper right is a root painted blue … possibly a reference to the blues and also to the rootless condition of African Americans. In the ghetto proper are a number of faces barely discernible, which blend into the ghetto. The entire composition is comprised of braided fabric from braided rugs that combine all the figures, thereby stressing their interconnectedness. Braiding of course refers to braided hair and to lynching, becoming a two-fold symbol. In addition, in the lower section of the painting is an iron cross painted in red.” [3]

Robert Hobbs suggests that the use of roots might reference “working the roots,” the African American practice of traditional folk magic, as well as the 1970s television series, Alex Haley’s Roots, although Dial is somewhat critical of the latter. [4] The artist recalls learning to draw out his ideas for making things from his job as a metal fabricator for the Pullman-Standard Railcar Manufacturing Company, but over the years Dial has learned to bypass an initial planning stage and instead works directly in fashioning his assemblages from discarded materials such as paint can lids, mops, chicken wire, mannequins, tin scraps, plastic figurines, and worn clothes. Here Dial unravels the braided rugs to use as a linear element, like a drawing. Maresca’s reference to the terrible legacy of lynching in the South, and Alabama in particular, as well as less horrific aspects of African American life, such as hair-braiding and modest household furnishings, exemplifies the multiplicity of meanings Dial can create through his astute selection of materials. The overall composition is literally tied and held together by the rope. The rope’s huge knots add visual complexity to the work; they are rhythmically arranged to project out from and return to the surface in a zigzag pattern, which suggests a physical representation of the call-and-response of traditional African American music.

The inclusion of a tiger, a prevalent symbol in Dial’s work between 1988 and 1992, is significant. It could symbolize a friend of the artist, Perry “Tiger” Thompson, who worked with him at the Pullman-Standard plant in Bessemer. Thompson, a former boxer, was an influential leader in the African American community in the pre-Civil Rights era, head of the local labor union, and host of a Sunday morning gospel radio show. Dial greatly admired Thompson for his pugnacious spirit and his struggle on behalf of others; he became an important symbol of strength in adversity. “There was a man at Pullman’s, where I used to work, whose name was Tiger and he used to struggle for the union. Everything in life is a struggle. That’s what I’m trying to say here.” [5] At other times, Dial’s tiger is emblematic generally of African American males and/or Dial himself specifically. Whenever the tiger is present, Dial is addressing the condition of the African American community, but this can be extended to the plight of all in the lower classes who are suffering in our society, “crying for jobs.”

Although collectors, critics, and several art historians have closely studied Dial’s life and analyzed his oeuvre, he and his work maintain a certain inscrutability. Much like another contemporary artist from the South, Jasper Johns, Dial deflects and defies a full analysis of his work, leaving the viewer with a sneaking suspicion that there is as much or more that has not been detected. According to the cultural critic and journalist, Greg Tate, this is probably intentional; “just as Blackfolk in America never stopped being Africanist music makers, they also never ceased to be Africanist image makers. The difference is they just did it in secret, in private, in disguise, using caution and discretion, under extreme pressure and in fear of violent consequences for exhibiting any thoughts, plans, or actions that might appear contrary (when not viscerally opposed) to a malevolently racist and classist social order. Some of the vertiginous mojo of Dial’s art can certainly be attributed to it being incubated in an underground Black culture, a non-disclosing culture, a culture of codes and ciphers whose ways and meaning were meant to appear strange, curious, chaotic, and primitive to outsiders.” [6]

William Arnett also responds to the challenge of understanding the multiple meanings and oblique qualities in Dial’s work: “Two essential elements of secrecy are improvisation and misdirection. Those qualities infused the arts with some necessary survival features: inscrutability, opacity, unpredictability, and the facility to exist in the open in the presence of a potentially dangerous adversary who could not be allowed to understand what he was really hearing and seeing. As art gradually made its way from the cemeteries to the woods to the backyards and ultimately to the front yards, it became larger and more overt, but maintained its secrecy by seeming to be unstructured, being composed of innocuous materials, and characterized by a ‘repellent’ aesthetic—at least for its time. It was not until expressionism, which was largely based on adaptations of African aesthetics, became Americanized by the abstract expressionists that the Euro-American aesthetic started to catch up, and the African American aesthetic became not only far less repellent but extremely influential.” [7]

Notes:

[1] Dial quoted in John Beardsley, “His Story/History,” in Thornton Dial in the 21st Century (Atlanta, GA: Tinwood Books in association with the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 2005), 285.

[2] John Beardsley, “His Story/History,” 290.

[3] Maresca, Ricco/Maresca Gallery to Robert Hobbs, May 19, 2007. Artist files, Reynolda House Museum of American Art.

[4] Hobbs in conversation with Kathleen F. G. Hutton, May 2008. Artist files, Reynolda House Museum of American Art.

[5] Dial quoted in Beardsley, “His Story/History,” 287.

[6] Greg Tate, “Thornton Dial: Free, Black, and Brightening up the Darkness of the World,” in Hard Truths: The Art of Thornton Dial, exhibition catalogue (New York: Indianapolis Museum of Art and Delmonico Books/Prestel Publishing, 2011), 34.

[7] William Arnett, “The Road from Emelle,” in Thornton Dial in the 21st Century, 15–16.

ProvenanceBefore 2006

Robert C. Hobbs (born 1946) and Jean Crutchfield, Richmond, VA. [1]

After 2006

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC, given by Robert C. Hobbs and Jean Crutchfield on December 21, 2006. [2]

Notes:

[1] Deed of Gift, Object File.

[2] See Note 1.

Exhibition History2008

New World Views: Gifts from Jean Crutchfield and Robert Hobbs

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC (5/20/2008-8/31/2008)

2016-2018

Off the Wall: Postmodern Art at Reynolda

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC (12/3/2016-6/11/2018)

2021

The Voyage of Life: Art, Allegory, and Community Response

Reynolda House Museum of American Art (7/16/2021 - 12/12/2021)

Published ReferencesReynolda House Museum of American Art, Reynolda: Her Muses, Her Stories , with contributions by Martha R. Severens and David Park Curry (Winston-Salem, N.C.: Reynolda House Museum of American Art affiliated with Wake Forest University, 2017). pg 246, 247

DepartmentAmerican Art

Crying in the Jungle, Crying for Jobs

Artist

Thornton Dial

(American, 1928 - 2016)

Date1996

Mediumenamel, oil, found objects including roots and rope bonded to canvas mounted on board

DimensionsOverall (approximate): 53 1/8 x 66 1/8 x 7 1/2 in. (134.9 x 168 x 19.1 cm)

Canvas: 52 1/8 x 64 1/8 x 1 3/4 in. (132.4 x 162.9 x 4.4 cm)

SignedTD

Credit LineGift of Jean Crutchfield and Robert Hobbs

Copyright© 2021 Estate of Thornton Dial / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Object number2006.2.1

DescriptionThornton Dial’s assemblage Crying in the Jungle, Crying for Jobs immediately confronts the viewer with the challenge of trying to visually absorb the entire composition. It exemplifies Dial’s working method: “I like to use the stuff that I know about, stuff that I know the feel of. There’s some kind of things I always have liked to make stuff with. I’m talking about tin, steel, copper, and aluminum, and also old wood, rope, old clothes, sand, rocks, wire, screen, toys, tree limbs and roots. You could say, ‘If Dial see it, he knows what to do with it.’” [1]The imagery of the visually active and tactile composition is masked by a mottled gray surface. The implicit and actual weight of the materials Dial has affixed to the canvas-covered plywood base project so far from the support that one supposes that parts might just fall off. The work is held together by a seemingly continuous length of roping, anchored to the support by large strong knots and sealant. Pinks, red, blue, and yellow paint are flecked over specific surface areas of the composition. Examined more intently, but at some distance, these colors highlight rope outlines of human figures and a stylized tiger. The work is signed T.D. just above the tiger, in the upper right corner.

Crying in the Jungle, Crying for Jobs is a heroic piece, created in the same year as the 1996 Summer Olympic Games in Atlanta, Georgia. Dial had a one-man exhibition at the Michael C. Carlos Museum at Emory University in Atlanta and was included in a group show as part of the cultural festivities. However, this artwork does not directly address global sports. It relates to Dial’s Tragedies period, almost certainly referencing the fallout from the disastrous Sixty Minutes television episode in 1993 when Morley Safer questioned the motivations of Dial’s patron William Arnett. Dial’s subsequent works do not have the overall vibrancy of earlier works, although they have more gravitas. [2]

In an assessment of the work, gallerist Frank Maresca offered the following interpretation: “The painting presents members of a white and African American oligarchy, who are painted from left to right in pink and in a light yellow pigment. In the upper right, just beyond center, Dial has inserted his signature tiger cat as a bruised creature, who emits light in the ghetto/jungle below. Also in the upper right is a root painted blue … possibly a reference to the blues and also to the rootless condition of African Americans. In the ghetto proper are a number of faces barely discernible, which blend into the ghetto. The entire composition is comprised of braided fabric from braided rugs that combine all the figures, thereby stressing their interconnectedness. Braiding of course refers to braided hair and to lynching, becoming a two-fold symbol. In addition, in the lower section of the painting is an iron cross painted in red.” [3]

Robert Hobbs suggests that the use of roots might reference “working the roots,” the African American practice of traditional folk magic, as well as the 1970s television series, Alex Haley’s Roots, although Dial is somewhat critical of the latter. [4] The artist recalls learning to draw out his ideas for making things from his job as a metal fabricator for the Pullman-Standard Railcar Manufacturing Company, but over the years Dial has learned to bypass an initial planning stage and instead works directly in fashioning his assemblages from discarded materials such as paint can lids, mops, chicken wire, mannequins, tin scraps, plastic figurines, and worn clothes. Here Dial unravels the braided rugs to use as a linear element, like a drawing. Maresca’s reference to the terrible legacy of lynching in the South, and Alabama in particular, as well as less horrific aspects of African American life, such as hair-braiding and modest household furnishings, exemplifies the multiplicity of meanings Dial can create through his astute selection of materials. The overall composition is literally tied and held together by the rope. The rope’s huge knots add visual complexity to the work; they are rhythmically arranged to project out from and return to the surface in a zigzag pattern, which suggests a physical representation of the call-and-response of traditional African American music.

The inclusion of a tiger, a prevalent symbol in Dial’s work between 1988 and 1992, is significant. It could symbolize a friend of the artist, Perry “Tiger” Thompson, who worked with him at the Pullman-Standard plant in Bessemer. Thompson, a former boxer, was an influential leader in the African American community in the pre-Civil Rights era, head of the local labor union, and host of a Sunday morning gospel radio show. Dial greatly admired Thompson for his pugnacious spirit and his struggle on behalf of others; he became an important symbol of strength in adversity. “There was a man at Pullman’s, where I used to work, whose name was Tiger and he used to struggle for the union. Everything in life is a struggle. That’s what I’m trying to say here.” [5] At other times, Dial’s tiger is emblematic generally of African American males and/or Dial himself specifically. Whenever the tiger is present, Dial is addressing the condition of the African American community, but this can be extended to the plight of all in the lower classes who are suffering in our society, “crying for jobs.”

Although collectors, critics, and several art historians have closely studied Dial’s life and analyzed his oeuvre, he and his work maintain a certain inscrutability. Much like another contemporary artist from the South, Jasper Johns, Dial deflects and defies a full analysis of his work, leaving the viewer with a sneaking suspicion that there is as much or more that has not been detected. According to the cultural critic and journalist, Greg Tate, this is probably intentional; “just as Blackfolk in America never stopped being Africanist music makers, they also never ceased to be Africanist image makers. The difference is they just did it in secret, in private, in disguise, using caution and discretion, under extreme pressure and in fear of violent consequences for exhibiting any thoughts, plans, or actions that might appear contrary (when not viscerally opposed) to a malevolently racist and classist social order. Some of the vertiginous mojo of Dial’s art can certainly be attributed to it being incubated in an underground Black culture, a non-disclosing culture, a culture of codes and ciphers whose ways and meaning were meant to appear strange, curious, chaotic, and primitive to outsiders.” [6]

William Arnett also responds to the challenge of understanding the multiple meanings and oblique qualities in Dial’s work: “Two essential elements of secrecy are improvisation and misdirection. Those qualities infused the arts with some necessary survival features: inscrutability, opacity, unpredictability, and the facility to exist in the open in the presence of a potentially dangerous adversary who could not be allowed to understand what he was really hearing and seeing. As art gradually made its way from the cemeteries to the woods to the backyards and ultimately to the front yards, it became larger and more overt, but maintained its secrecy by seeming to be unstructured, being composed of innocuous materials, and characterized by a ‘repellent’ aesthetic—at least for its time. It was not until expressionism, which was largely based on adaptations of African aesthetics, became Americanized by the abstract expressionists that the Euro-American aesthetic started to catch up, and the African American aesthetic became not only far less repellent but extremely influential.” [7]

Notes:

[1] Dial quoted in John Beardsley, “His Story/History,” in Thornton Dial in the 21st Century (Atlanta, GA: Tinwood Books in association with the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 2005), 285.

[2] John Beardsley, “His Story/History,” 290.

[3] Maresca, Ricco/Maresca Gallery to Robert Hobbs, May 19, 2007. Artist files, Reynolda House Museum of American Art.

[4] Hobbs in conversation with Kathleen F. G. Hutton, May 2008. Artist files, Reynolda House Museum of American Art.

[5] Dial quoted in Beardsley, “His Story/History,” 287.

[6] Greg Tate, “Thornton Dial: Free, Black, and Brightening up the Darkness of the World,” in Hard Truths: The Art of Thornton Dial, exhibition catalogue (New York: Indianapolis Museum of Art and Delmonico Books/Prestel Publishing, 2011), 34.

[7] William Arnett, “The Road from Emelle,” in Thornton Dial in the 21st Century, 15–16.

ProvenanceBefore 2006

Robert C. Hobbs (born 1946) and Jean Crutchfield, Richmond, VA. [1]

After 2006

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC, given by Robert C. Hobbs and Jean Crutchfield on December 21, 2006. [2]

Notes:

[1] Deed of Gift, Object File.

[2] See Note 1.

Exhibition History2008

New World Views: Gifts from Jean Crutchfield and Robert Hobbs

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC (5/20/2008-8/31/2008)

2016-2018

Off the Wall: Postmodern Art at Reynolda

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC (12/3/2016-6/11/2018)

2021

The Voyage of Life: Art, Allegory, and Community Response

Reynolda House Museum of American Art (7/16/2021 - 12/12/2021)

Published ReferencesReynolda House Museum of American Art, Reynolda: Her Muses, Her Stories , with contributions by Martha R. Severens and David Park Curry (Winston-Salem, N.C.: Reynolda House Museum of American Art affiliated with Wake Forest University, 2017). pg 246, 247

Status

Not on view