Skip to main content

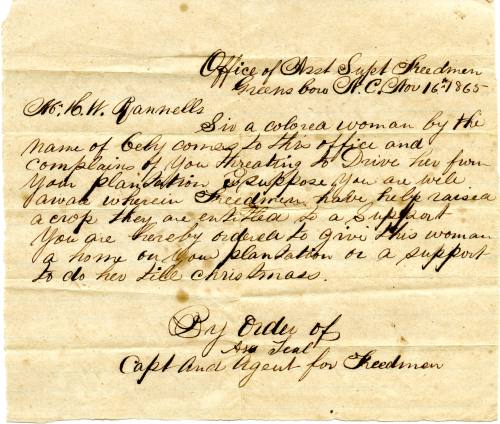

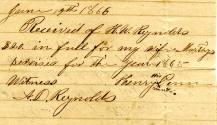

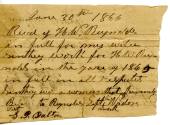

At the time of the Civil War, Hardin Reynolds owned more than 60 enslaved persons on his property Rock Spring Plantation in Critz, Virginia. Hardin’s tobacco plantation survived the war and he transitioned from enslaved labor to using Black tenant labor or sharecroppers. Hardin paid very little, drew up harsh contracts, and often would not fulfill his agreements. These documents record Hardin Reynolds’ transactions with freedmen and women working as tenant farmers on his property. On November 16, 1865, the Freedmen’s Bureau wrote to Hardin Reynolds, advocating on behalf of Cely, who had been denied pay and who Hardin threatened to remove from the property. As Hardin Reynolds struggled to adapt to this new economy, other tenant farmers sued to receive money they were owed for their work. A March 3, 1866 receipt shows the money owed to Peter Reynolds and his family, and a June 17, 1866 receipt describes the tenant labor performed by Henry Penn’s wife Murthy.

These documents serve as an ever present reminder of the role that human property played in the tobacco industry. The tobacco industry relied on Black labor, first as enslaved workers then as free labor. The notion that Black people were best suited for work in tobacco factories has its roots in slavery, when overseers and White capitalists commonly believed that Black people were better able to withstand the long hours, physical demands, and unsanitary conditions of tobacco production.

ProvenanceThe Reynolds Family Papers were transferred from Wake Forest University in 1993 when Reynolda House Museum of American Art established its archives. The bulk of this collection was originally received by Wake Forest University in a series of gifts from Nancy Susan Reynolds, 15 May 1976 and 22 February 1982, and from Reynolda House, Inc., 13 August 1976, 30 November 1976, 15 June 1978, 6 October 1980, 28 October 1980, and 26 January 1981.

Exhibition History2022-2023

Still I Rise: The Black Experience at Reynolda

Reynolda House Museum of American Art

DepartmentEstate Archives

Hardin William Reynolds Freedmen Records

Date1865-1866

MediumDocument

Credit LineReynolda House Museum of American Art

CopyrightPublic Domain

Object numberEA.1865.001

DescriptionR.J. Reynolds’ father, Hardin William Reynolds, owned thousands of acres of land and was one of the largest slaveholders in the Patrick County area of Virginia. Hardin, a shrewd businessman, recognized that manufacturing tobacco products was far more profitable than growing the leaf alone; by the time R.J. was born in 1850, the tobacco factory was Hardin’s primary source of income. Young R.J. grew up working the floor of his father’s tobacco factory. He learned not only the mechanics of the factory but also the value of one flavoring over another, the factors that could lead to fluctuations in tobacco prices, and how to select the choicest leaf. In later life, R.J. would use the story of working as a hand in his father’s factory to ingratiate himself with his own workers. While technically true, he did so as the slaveholder’s son. At the time of the Civil War, Hardin Reynolds owned more than 60 enslaved persons on his property Rock Spring Plantation in Critz, Virginia. Hardin’s tobacco plantation survived the war and he transitioned from enslaved labor to using Black tenant labor or sharecroppers. Hardin paid very little, drew up harsh contracts, and often would not fulfill his agreements. These documents record Hardin Reynolds’ transactions with freedmen and women working as tenant farmers on his property. On November 16, 1865, the Freedmen’s Bureau wrote to Hardin Reynolds, advocating on behalf of Cely, who had been denied pay and who Hardin threatened to remove from the property. As Hardin Reynolds struggled to adapt to this new economy, other tenant farmers sued to receive money they were owed for their work. A March 3, 1866 receipt shows the money owed to Peter Reynolds and his family, and a June 17, 1866 receipt describes the tenant labor performed by Henry Penn’s wife Murthy.

These documents serve as an ever present reminder of the role that human property played in the tobacco industry. The tobacco industry relied on Black labor, first as enslaved workers then as free labor. The notion that Black people were best suited for work in tobacco factories has its roots in slavery, when overseers and White capitalists commonly believed that Black people were better able to withstand the long hours, physical demands, and unsanitary conditions of tobacco production.

ProvenanceThe Reynolds Family Papers were transferred from Wake Forest University in 1993 when Reynolda House Museum of American Art established its archives. The bulk of this collection was originally received by Wake Forest University in a series of gifts from Nancy Susan Reynolds, 15 May 1976 and 22 February 1982, and from Reynolda House, Inc., 13 August 1976, 30 November 1976, 15 June 1978, 6 October 1980, 28 October 1980, and 26 January 1981.

Exhibition History2022-2023

Still I Rise: The Black Experience at Reynolda

Reynolda House Museum of American Art

Status

Not on view