Skip to main content

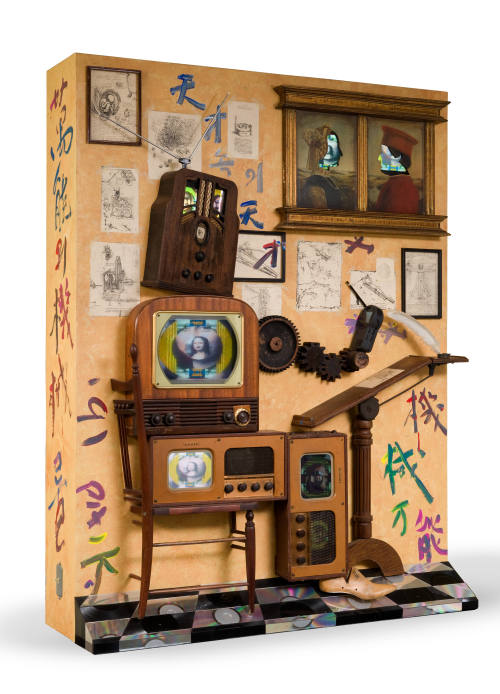

The brightly colored, flickering images on the multiple monitors of Paik’s video sculpture are what initially capture the attention of the viewer who gradually realizes that many, if not all, of the art reproductions are by Leonardo da Vinci, in concert with the title of the piece. Eventually the viewer comprehends, or has it pointed out, that this assortment of technological and found objects itself constitutes a scene—in fact, an interior room in which a robot in three-quarter profile is seated at a drawing table, sketching, with arm outstretched towards a quill pen on his table. The robot’s head is an old radio cabinet, with two small television monitors behind the speakers. A large antique television cabinet, fitted with a color monitor, forms the torso. Four wooden interlocking gears, progressively diminishing to the wrist, suggest the outstretched arm. The implied hand is in fact a Sony Watchman portable television. The upper and lower leg are created by two similar antique Crosley radio cabinets, fitted with two monitors housed in each cabinet, and a wooden shoe form becomes the foot.

On the yellow wall of the “room,” presumably an artist’s studio, is a diptych of two profiles, a man and a woman whose images have been curiously altered, and many drawings, haphazardly displayed, fixed to the wall with diagonal bits of masking tape over the corners. The space features a large checkerboard tile floor, arranged according to Renaissance-era linear perspective. Paik’s assemblage is a direct homage to the fifteenth-century Italian High Renaissance artist Leonardo da Vinci and is one of four relief sculptures produced for the exhibition Casino Knokke, a reference to Knokke-le Zoute in West Flanders, the site of a Belgian avant-garde and experimental film festival founded by the Belgian film historian Jacques Ledoux. Paik’s anthropomorphic bricolages celebrate creative geniuses whom the artist admired: along with Leonardo, the others are astronomer Galileo Galilei, physicist Isaac Newton, and biologist Charles Darwin.

The viewer can delight in the playfulness of Paik’s many references to Leonardo and the Renaissance, from the development of perspective to the Italian master’s iconic portrait Mona Lisa, the fresco of The Last Supper, and his drawing of The Vitruvian Man. Many more works attributed to Leonardo are recognizable in the rapid-fire presentation of images on the screen monitors. Leonardo was groundbreaking in his day in various scientific areas of study: anatomy, botany, physics—especially fluid mechanics, aerodynamics, and flight—and military engineering. Paik has selected images to reflect Leonardo’s diverse interests. Visible are his study of anatomy in The Vitruvian Man and a fetus in the womb; botany is represented by a drawing of the Star of Bethlehem plant. Leonardo’s understanding of geometry inspires the drawing of a dodecahedron, and there are several machines: various flying devices, a spring-driven four-wheel vehicle, a clock spring regulator, a bobbin winder, and the robot’s drawing of his improvement for the printing press. Although not a work by Leonardo, the inclusion of the familiar diptych portraits of the Duchess and Duke of Urbino by Piero della Francesca at the upper right may be a nod by Paik to another Renaissance genius who was an artist, mathematician, and philosopher. Especially striking is the Duke’s distinctive profile—he was missing much of his nose from a jousting accident—which Paik has altered further by cutting out the profiles of him and the Duchess to reveal monitor screens behind.

Paik created unique recordings on two laser disks. There are ten screens; one video plays on the diptych heads, the torso screen, and the Watchman. The remaining six screens, in the eyes and legs, display the other video. The video loop includes digital manipulation of images, short segments of video, details of Leonardo’s artwork, drawings, or contemporary models of his designs but there is no narrative implicit in the work. The laser disk players are placed in the base of the sculpture and are connected to the ten monitors. Thus the work presents multiple screenings of two related digital sequences. All the monitors are fitted into antique cabinets except the Sony Watchman, a portable pocket television, this one is from the FD-280/285 series made between 1990 and 1994. There is intentional irony; the television cabinets that originally would have shown programs broadcast in black and white now have color imagery, while the only modern and non-modified television, the Watchman, has a black and white CRT display. On closer examination, the floor squares are alternately made of cut black vinyl records and shiny laser discs. Because laser discs are no longer produced, most viewers assume that they see another type of optical disc storage for digital data, such as a CD (compact disc) or a DVD (digital versatile disc). Although an earlier audio technology, the LP (Long Playing) 33-1/3 rpm vinyl records are more easily recognized by contemporary viewers.

Leonardo da Vinci is related to an earlier Paik series, the Family of Robot begun in 1986. “With Family of Robot Paik developed a principle that he had until then applied only to individual objects: the use of old television and radio cabinets with updated engineering fitted inside. The result is the charm of old objects, which additionally provide documentation of media history. … Paik used to avoid fitting monitors into cabinets, but the robots represent the beginning of a new phase that makes this precisely the working principle for installations.” [2] Also necessary to the installation process for Leonardo and the others is that the sculptures are not free-standing in the round but are in haut-relief, with their backs hidden from view and their sides less interesting than the main frontal view.

Nam June Paik evoked a sense of global graffiti by painting Chinese and Korean ideograms over the painted yellow canvas “skin” of his sculpture. The artist noted that the Korean characters above the head of the robot translate as “the genius among geniuses” while the characters in the lower front right are “machine,” “panacea=omnipotence,” and “can do everything.” [3] He also did a sketchy painting of an airplane over some Leonardo drawings of a glider. On either side of the sculpture are more Chinese characters that mean “infinitely able genius machinery,” which seems to glorify both artist and technology. Paik signed and dated the work vertically along the front left edge of the sculpture.

Paik mused that he “was preoccupied by the ancient theory of ‘mimesis’ which maintains that sculpture imitates forms, painting imitates idols, that music imitates bird song. And I asked myself, ‘What does video imitate?’ I discovered that the art of video imitated the essence of time passing. …Video enables me to go back in time; I can bring the past into the present and plunge the present back three thousand years into the past.” [4]

It is important to note the state of technology in 1991 when Paik created this artwork—both the projections and, even more, his “collage” of light, the video montage. While Microsoft and Apple had been founded in 1975 and 1976, respectively, it had only been a decade since IBM introduced the first personal computer. Sony introduced the first 3.5-inch floppy disk drive in 1981, followed three years later by Apple’s Macintosh computer. In 1987 came the first IBM PS/2 computers. In 1990, the World Wide Web, or Internet, was born, when Tim Berners-Lee devised HTML (hypertext markup language). Ever forward-looking, Paik anticipated and granted Reynolda House Museum of American Art permission to upgrade the technology as required, subject to maintaining the original visual appearance of the work. Individual monitors have been swapped out and laser disc players have been replaced by DVDs. Paik created a work that will always be about the evolving history of technology.

Notes:

[1] Otto Hahn, “Interview,” in Nam June Paik: Casino Knokke, exhibition catalogue (Cincinnati OH: Knokke-Heist in conjunction with Carl Solway Gallery, 1992), unpaginated.

[2] Edith Decker, “Hardware,” in Nam June Paik: Video Time—Video Space (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1993), 70.

[3] Artist note, object file in the collection of Reynolda House Museum of American Art.

[4] Hahn, “Interview,” unpaginated.

Provenance1993

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC, purchased from Carl Solway Gallery, Cincinnati, OH on May 24, 1993. [1]

Notes:

[1] Invoice, Object file.

Exhibition History2006

Self/Image: Portraiture from Copley to Close

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC (8/30/2006-12/31/2006)

Published ReferencesReynolda House Museum of American Art, Reynolda: Her Muses, Her Stories , with contributions by Martha R. Severens and David Park Curry (Winston-Salem, N.C.: Reynolda House Museum of American Art affiliated with Wake Forest University, 2017). pg 196, 230, 231

DepartmentAmerican Art

Leonardo da Vinci

Artist

Nam June Paik

(1932 - 2006)

Date1991

Medium3 antique TV cabinets, 1 antique radio cabinet, antique drawing table, chair, painting reproductions, paint, canvas, 1 sony 13" TV, two 8" TVs, 4 KTV 4.5" TVs, two 9" KTVs, 1 watchman, laser disk players, 2 paik laser disks

DimensionsOverall (with base & wheels): 93 x 64 x 21 in. (236.2 x 162.6 x 53.3 cm)

Overall (with base): 91 x 64 x 21 in. (231.1 x 162.6 x 53.3 cm)

Overall (without base): 77 1/2 x 60 x 20 1/8 in. (196.9 x 152.4 x 51.1 cm)

Signed’91 PAIK.

Credit LineMuseum Purchase with additional funds provided by Barbara B. Millhouse

Copyright© Estate of Nam June Paik

Object number1993.2.1

DescriptionIn an interview in 1992, the Korean-American artist Nam June Paik responded to a question about the use of old television sets to screen electronic manipulations of digital imagery. He responded: “To me old television sets resemble sculptures. When I play back an electronic image on an old set I create an interesting tension. Like all human beings I need balance in my life; if I make a really exciting video, I need to compensate this and balance it out with an old television set.” [1]The brightly colored, flickering images on the multiple monitors of Paik’s video sculpture are what initially capture the attention of the viewer who gradually realizes that many, if not all, of the art reproductions are by Leonardo da Vinci, in concert with the title of the piece. Eventually the viewer comprehends, or has it pointed out, that this assortment of technological and found objects itself constitutes a scene—in fact, an interior room in which a robot in three-quarter profile is seated at a drawing table, sketching, with arm outstretched towards a quill pen on his table. The robot’s head is an old radio cabinet, with two small television monitors behind the speakers. A large antique television cabinet, fitted with a color monitor, forms the torso. Four wooden interlocking gears, progressively diminishing to the wrist, suggest the outstretched arm. The implied hand is in fact a Sony Watchman portable television. The upper and lower leg are created by two similar antique Crosley radio cabinets, fitted with two monitors housed in each cabinet, and a wooden shoe form becomes the foot.

On the yellow wall of the “room,” presumably an artist’s studio, is a diptych of two profiles, a man and a woman whose images have been curiously altered, and many drawings, haphazardly displayed, fixed to the wall with diagonal bits of masking tape over the corners. The space features a large checkerboard tile floor, arranged according to Renaissance-era linear perspective. Paik’s assemblage is a direct homage to the fifteenth-century Italian High Renaissance artist Leonardo da Vinci and is one of four relief sculptures produced for the exhibition Casino Knokke, a reference to Knokke-le Zoute in West Flanders, the site of a Belgian avant-garde and experimental film festival founded by the Belgian film historian Jacques Ledoux. Paik’s anthropomorphic bricolages celebrate creative geniuses whom the artist admired: along with Leonardo, the others are astronomer Galileo Galilei, physicist Isaac Newton, and biologist Charles Darwin.

The viewer can delight in the playfulness of Paik’s many references to Leonardo and the Renaissance, from the development of perspective to the Italian master’s iconic portrait Mona Lisa, the fresco of The Last Supper, and his drawing of The Vitruvian Man. Many more works attributed to Leonardo are recognizable in the rapid-fire presentation of images on the screen monitors. Leonardo was groundbreaking in his day in various scientific areas of study: anatomy, botany, physics—especially fluid mechanics, aerodynamics, and flight—and military engineering. Paik has selected images to reflect Leonardo’s diverse interests. Visible are his study of anatomy in The Vitruvian Man and a fetus in the womb; botany is represented by a drawing of the Star of Bethlehem plant. Leonardo’s understanding of geometry inspires the drawing of a dodecahedron, and there are several machines: various flying devices, a spring-driven four-wheel vehicle, a clock spring regulator, a bobbin winder, and the robot’s drawing of his improvement for the printing press. Although not a work by Leonardo, the inclusion of the familiar diptych portraits of the Duchess and Duke of Urbino by Piero della Francesca at the upper right may be a nod by Paik to another Renaissance genius who was an artist, mathematician, and philosopher. Especially striking is the Duke’s distinctive profile—he was missing much of his nose from a jousting accident—which Paik has altered further by cutting out the profiles of him and the Duchess to reveal monitor screens behind.

Paik created unique recordings on two laser disks. There are ten screens; one video plays on the diptych heads, the torso screen, and the Watchman. The remaining six screens, in the eyes and legs, display the other video. The video loop includes digital manipulation of images, short segments of video, details of Leonardo’s artwork, drawings, or contemporary models of his designs but there is no narrative implicit in the work. The laser disk players are placed in the base of the sculpture and are connected to the ten monitors. Thus the work presents multiple screenings of two related digital sequences. All the monitors are fitted into antique cabinets except the Sony Watchman, a portable pocket television, this one is from the FD-280/285 series made between 1990 and 1994. There is intentional irony; the television cabinets that originally would have shown programs broadcast in black and white now have color imagery, while the only modern and non-modified television, the Watchman, has a black and white CRT display. On closer examination, the floor squares are alternately made of cut black vinyl records and shiny laser discs. Because laser discs are no longer produced, most viewers assume that they see another type of optical disc storage for digital data, such as a CD (compact disc) or a DVD (digital versatile disc). Although an earlier audio technology, the LP (Long Playing) 33-1/3 rpm vinyl records are more easily recognized by contemporary viewers.

Leonardo da Vinci is related to an earlier Paik series, the Family of Robot begun in 1986. “With Family of Robot Paik developed a principle that he had until then applied only to individual objects: the use of old television and radio cabinets with updated engineering fitted inside. The result is the charm of old objects, which additionally provide documentation of media history. … Paik used to avoid fitting monitors into cabinets, but the robots represent the beginning of a new phase that makes this precisely the working principle for installations.” [2] Also necessary to the installation process for Leonardo and the others is that the sculptures are not free-standing in the round but are in haut-relief, with their backs hidden from view and their sides less interesting than the main frontal view.

Nam June Paik evoked a sense of global graffiti by painting Chinese and Korean ideograms over the painted yellow canvas “skin” of his sculpture. The artist noted that the Korean characters above the head of the robot translate as “the genius among geniuses” while the characters in the lower front right are “machine,” “panacea=omnipotence,” and “can do everything.” [3] He also did a sketchy painting of an airplane over some Leonardo drawings of a glider. On either side of the sculpture are more Chinese characters that mean “infinitely able genius machinery,” which seems to glorify both artist and technology. Paik signed and dated the work vertically along the front left edge of the sculpture.

Paik mused that he “was preoccupied by the ancient theory of ‘mimesis’ which maintains that sculpture imitates forms, painting imitates idols, that music imitates bird song. And I asked myself, ‘What does video imitate?’ I discovered that the art of video imitated the essence of time passing. …Video enables me to go back in time; I can bring the past into the present and plunge the present back three thousand years into the past.” [4]

It is important to note the state of technology in 1991 when Paik created this artwork—both the projections and, even more, his “collage” of light, the video montage. While Microsoft and Apple had been founded in 1975 and 1976, respectively, it had only been a decade since IBM introduced the first personal computer. Sony introduced the first 3.5-inch floppy disk drive in 1981, followed three years later by Apple’s Macintosh computer. In 1987 came the first IBM PS/2 computers. In 1990, the World Wide Web, or Internet, was born, when Tim Berners-Lee devised HTML (hypertext markup language). Ever forward-looking, Paik anticipated and granted Reynolda House Museum of American Art permission to upgrade the technology as required, subject to maintaining the original visual appearance of the work. Individual monitors have been swapped out and laser disc players have been replaced by DVDs. Paik created a work that will always be about the evolving history of technology.

Notes:

[1] Otto Hahn, “Interview,” in Nam June Paik: Casino Knokke, exhibition catalogue (Cincinnati OH: Knokke-Heist in conjunction with Carl Solway Gallery, 1992), unpaginated.

[2] Edith Decker, “Hardware,” in Nam June Paik: Video Time—Video Space (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1993), 70.

[3] Artist note, object file in the collection of Reynolda House Museum of American Art.

[4] Hahn, “Interview,” unpaginated.

Provenance1993

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC, purchased from Carl Solway Gallery, Cincinnati, OH on May 24, 1993. [1]

Notes:

[1] Invoice, Object file.

Exhibition History2006

Self/Image: Portraiture from Copley to Close

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC (8/30/2006-12/31/2006)

Published ReferencesReynolda House Museum of American Art, Reynolda: Her Muses, Her Stories , with contributions by Martha R. Severens and David Park Curry (Winston-Salem, N.C.: Reynolda House Museum of American Art affiliated with Wake Forest University, 2017). pg 196, 230, 231

Status

Not on view