Skip to main content

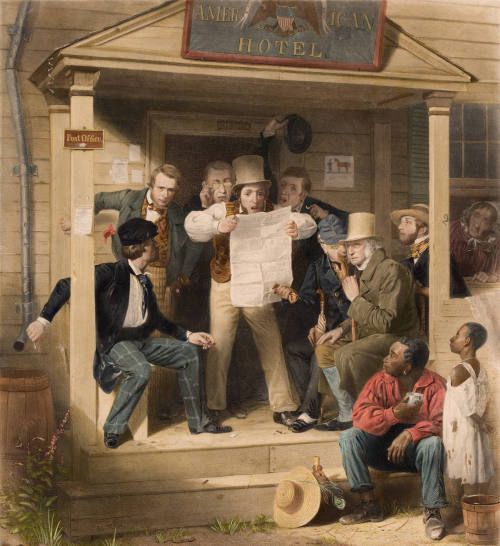

Woodville’s image depicts a group of men gathered on the front porch of the fictitious and aptly named American Hotel. The figure in the center has just rushed in with the latest news of the Mexican-American War (1846–1848). As he reads the paper, the characters around him register varying degrees of interest, concern, and fear. The war had enormous political implications for the entire nation. The end of the war would mean the annexation of extensive lands that would become California, New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, Nevada, and parts of Colorado. In addition, the country faced a decision about which of the new territories would be slave states and which would be free. All of the men assembled on the porch would have been able to participate in the decision-making process by voting for their congressional representatives.

Standing outside the porch, however, are three figures who would not have been able to take part in this process—a black man and his daughter near the steps and a white woman leaning out of the window. Their lives will be affected by the outcome of the war, and they listen intently to the news, but, unable to vote, they have no say in the political arena. Significantly, they stand outside of the shelter of the American Hotel’s porch, and therefore do not receive its protection.

Woodville gives the viewer a clue about where his sympathies lie through his vivid characterization of the black father and daughter. The expression on the man’s face reflects a heartbreaking mixture of eagerness and apprehension—eagerness perhaps about the possibilities for a new life in the West, apprehension about the potential expansion of slavery. His daughter’s threadbare shift would have elicited a sympathetic reaction from Woodville’s contemporary viewers. Furthermore, the two figures together wear the colors red, white, and blue, underscoring the point that they are American, albeit Americans of reduced rights, privileges, and circumstances. [2]

In Woodville’s composition, the newspaper takes center stage. This prominent detail reflects the spread of fast and affordable printing—the result of technological improvements in machinery, paper, and ink—that made newspapers and broadsides more obtainable. These developments also made possible the production of fine art prints. Companies such as Currier and Ives, founded in 1835, and Louis Prang and Co., established in 1856, sold color lithographs as cheaply as twenty-five cents per copy, making them widely accessible to a middle class eager for symbols of refinement. Hand-colored engravings of images like Woodville’s War News from Mexico—so popular that its initial print run totaled 14,000—were treated by consumers much like paintings: framed and displayed proudly in the parlor. Thus, the mid-nineteenth century witnessed an extraordinary democratization of art, in which the moral visions of artists and patrons were widely disseminated throughout the country.

Notes:

[1] David B. Dearinger, Paintings and Sculpture in the Collection of the National Academy of Design (Manchester, VT: Hudson Hills Press, 2004), 325.

[2] Justin P. Wolff, Richard Caton Woodville: American Painter, Artful Dodger (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2002), 107.

ProvenanceTo 1983

Barbara B. Millhouse, New York, NY and Winston-Salem, NC [1]

From 1983

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC, given by Barbara B. Millhouse on December 29, 1983. [2]

Notes:

[1] Deed of Gift, object file.

[2] See note 1.

Exhibition History2010

Virtue, Vice, Wisdom & Folly: The Moralizing Tradition in American Art

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC (9/18/201-12/31/2010)

2017

Samuel F.B. Morse's Gallery of the Louvre and the Art of Invention

Reynolda House Museum of American Art (02/17/2017 - 06/04/2017)

Published References

DepartmentAmerican Art

Mexican News

Artist(after)

Richard Caton Woodville

(1825 - 1855)

Date1851

Mediumhand-colored engraving

DimensionsFrame: 27 1/2 x 24 1/2 in. (69.9 x 62.2 cm)

Image(without text): 20 1/2 x 18 1/2 in. (52.1 x 47 cm)

SignedEngraved by Alfred Jones

Credit LineGift of Barbara B. Millhouse

CopyrightPublic Domain

Object number1983.2.36

DescriptionRichard Caton Woodville’s 1848 painting War News from Mexico was extraordinarily popular in the nineteenth century, and it remains one of the most recognized American genre paintings. The American Art-Union purchased the painting in 1849 and commissioned Alfred Jones to make an engraving, retitled Mexican News, for distribution to its members. Jones had studied engraving as an apprentice in Albany, New York. After moving to New York City, his talents as an engraver were highly prized by such institutions as the American Art-Union. He also took classes at the National Academy of Design where he was elected a full academician in 1851. In addition to the engraving after Woodville’s painting, Jones engraved works by Asher B. Durand, William Sidney Mount, and others. In his later years, he worked primarily as an engraver of bank notes and postage stamps. [1]Woodville’s image depicts a group of men gathered on the front porch of the fictitious and aptly named American Hotel. The figure in the center has just rushed in with the latest news of the Mexican-American War (1846–1848). As he reads the paper, the characters around him register varying degrees of interest, concern, and fear. The war had enormous political implications for the entire nation. The end of the war would mean the annexation of extensive lands that would become California, New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, Nevada, and parts of Colorado. In addition, the country faced a decision about which of the new territories would be slave states and which would be free. All of the men assembled on the porch would have been able to participate in the decision-making process by voting for their congressional representatives.

Standing outside the porch, however, are three figures who would not have been able to take part in this process—a black man and his daughter near the steps and a white woman leaning out of the window. Their lives will be affected by the outcome of the war, and they listen intently to the news, but, unable to vote, they have no say in the political arena. Significantly, they stand outside of the shelter of the American Hotel’s porch, and therefore do not receive its protection.

Woodville gives the viewer a clue about where his sympathies lie through his vivid characterization of the black father and daughter. The expression on the man’s face reflects a heartbreaking mixture of eagerness and apprehension—eagerness perhaps about the possibilities for a new life in the West, apprehension about the potential expansion of slavery. His daughter’s threadbare shift would have elicited a sympathetic reaction from Woodville’s contemporary viewers. Furthermore, the two figures together wear the colors red, white, and blue, underscoring the point that they are American, albeit Americans of reduced rights, privileges, and circumstances. [2]

In Woodville’s composition, the newspaper takes center stage. This prominent detail reflects the spread of fast and affordable printing—the result of technological improvements in machinery, paper, and ink—that made newspapers and broadsides more obtainable. These developments also made possible the production of fine art prints. Companies such as Currier and Ives, founded in 1835, and Louis Prang and Co., established in 1856, sold color lithographs as cheaply as twenty-five cents per copy, making them widely accessible to a middle class eager for symbols of refinement. Hand-colored engravings of images like Woodville’s War News from Mexico—so popular that its initial print run totaled 14,000—were treated by consumers much like paintings: framed and displayed proudly in the parlor. Thus, the mid-nineteenth century witnessed an extraordinary democratization of art, in which the moral visions of artists and patrons were widely disseminated throughout the country.

Notes:

[1] David B. Dearinger, Paintings and Sculpture in the Collection of the National Academy of Design (Manchester, VT: Hudson Hills Press, 2004), 325.

[2] Justin P. Wolff, Richard Caton Woodville: American Painter, Artful Dodger (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2002), 107.

ProvenanceTo 1983

Barbara B. Millhouse, New York, NY and Winston-Salem, NC [1]

From 1983

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC, given by Barbara B. Millhouse on December 29, 1983. [2]

Notes:

[1] Deed of Gift, object file.

[2] See note 1.

Exhibition History2010

Virtue, Vice, Wisdom & Folly: The Moralizing Tradition in American Art

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC (9/18/201-12/31/2010)

2017

Samuel F.B. Morse's Gallery of the Louvre and the Art of Invention

Reynolda House Museum of American Art (02/17/2017 - 06/04/2017)

Published References

Status

Not on view