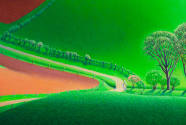

Spring Turning

A high horizon line running along the exaggerated width of the composition paradoxically creates simultaneous feelings of expansion and compression in this depiction of an eastern Iowa landscape. The primary subject of Spring Turning, 1936, an oil painting on Masonite panel, is the remembered landscape of Grant Wood’s childhood in Anamosa, Iowa. There is no visual evidence of twentieth century progress in this setting—no automobiles, farm machinery, paved roads, or electric wires. Wood scholar Wanda Corn describes it as “man liv(ing) in complete harmony with nature; he is the earth’s caretaker, coaxing her into abundance, bringing coherence and beauty to her surfaces” (see Wanda Corn, Grant Wood: The Regionalist Vision, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1983, 90). The painting was first exhibited at the Carnegie International Exhibition in Pittsburgh in 1936 and on February 8, 1937 was featured in a full-color two-page spread in Life magazine (see Erika Doss, Benton, Pollock and the Politics of Modernism, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991, 175).

The landscape shown has been segmented into fields for cultivation. The composition encompasses four fields, side by side in pairs and receding at a diagonal away from the picture plane. Their geometric demarcation is man-made, indicated by the plowed furrows that are being turned under in preparation for planting, the rusty red-orange furrows highlighted against the velvety green growth. Each field is surrounded by posthole fences. One can see the fence posts but not the strung wires, thus reinforcing the repetition of the posts as hemmed stitches on a vast quilt. The left of the rear fields has been completely plowed, while the other three are in the process of being plowed. The tiny form of a farmer works the square from the outside to its center. There is a hint of one work-team silhouetted against the sky. The foreground field is being worked by a farmer and team of draft horses, while the mid-ground field is being worked by a farmer driving a team of oxen. In the bottom right third of the composition, a small bridge crosses a shaded stream. At the far end of the recessional diagonal created by the contour of the foreground hill is a single tree casting a shadow, as if in response to the distant pink-flowering tree back by the foot bridge. Along the left edge of the composition, tucked into the far side of a hill, a farmhouse is partly visible, along with grazing cattle in the adjoining field. Slightly above and to the right, barely visible against the sky on the farthest hill, is yet another work team, while the next hill over is topped by a very tiny weathervane against the sky. The bright blue sky is scattered with clouds, but rather than appear rounded these clouds seem to square themselves up parallel to the fields below them. The overall dominance of geometric forms in this landscape and an almost deliberate minimization of pattern and decoration may be traced to Wood’s studies under Ernest Batchelder. Specifically, critic James Dennis says that Batchelder would have been familiar with the art teachings of Arthur Wesley Dow, whose art manual Composition was first published in 1899 and was reissued several times through the 1940s. A quote of Dow’s seems especially applicable to Spring Turning: “Take any landscape that has some good elements in it, reduce it to a few main lines, and strive to present it in the most beautiful way” (see James M. Dennis, Renegade Regionalists: The modern independence of Grant Wood, Thomas Hart Benton, and John Steuart Curry, Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1998, 185).

While studying in Munich in 1928 , Grant Wood grew to admire the Northern Renaissance artists Jan van Eyck, Hans Memling, and Hans Holbein the Younger, and this admiration is evident in his most celebrated artwork, American Gothic (1930). Instead of a donor and saint with attributes, there are a farmer and farmwoman. Wood originally intended the pair to be father and spinster daughter but they have generally been perceived as a married couple. The highly realistic depiction is heightened by the almost non-detectible brushwork and glazed surfaces. Wood’s attention to telling detail, such as the rickrack trim on the farmwoman’s apron, her cameo, and the Gothic tracery in the vernacular architecture of the farmhouse, can also be found in Spring Turning. All the details of Spring Turning were worked out in the full-scale preparatory drawing, now in the collection of the Huntington Library and Art Gallery (see Study for Spring Turning, 1936. Pencil, charcoal, and chalk on paper, 17 1/2 in x 39 ¾ in. In the collection of the Henry E. Huntington Library and Art Gallery, San Marino, California. Gift of the Virginia Steele Scott Foundation, 83.8.53). In both the study and the painting, the cottonwood trees along the stream in the lower right-hand corner, the fence post “stitching” in the square fields created by the initial outmost furrow of each field, and the visual “stippling” of cattle on the hillside behind the farmhouse have a hypnotic effect upon the viewer. Although Wood employs the basic tools of linear perspective in the recession of forms into deep space, he also activates the picture plane by use of careful brushwork, as in his crosshatching light and darker green in the fields and the squared-off strokes of light on dark sienna brown to show the plowed earth in the near fields that eventually smooth to ribbon in the distance. The viewer’s gaze is kept within the composition by the horizontal tilt-up of the landscape towards the picture plane, which also has the effect of directing the viewer’s gaze away from the observation of minute details to seeing the overall geometric forms of the landscape. As his fellow Regionalist painter Thomas Hart Benton often did, Wood created a scale model in clay prior to painting his canvas, in order to accurately depict the shadows that would be cast. The support of this painting is the smooth side of a Masonite panel, with a commercial white oil-based paint as the ground and incorporating drawing and multiple layers of transparent, pigmented glazes made from equal parts linseed oil, damar varnish, turpentine and oil paint. The significant use of modifiers to the paint may be the cause of wrinkling and craquelure that can be found in this and other of Wood’s painted surfaces (see James Horns and Helen Mar Parkin, “Grant Wood: A Technical Study,” in Grant Wood: An American Master Revealed, San Francisco: Pomegranate Artbooks for Davenport Museum of Art, 1995, 85).

Wood’s landscape paintings and lithographs capture the seasonal motifs of farming, i.e. spring planting, summer hoeing, fall plowing and fallow fields in winter. Although raised on a farm until a teenager, Grant Wood never considered becoming a farmer himself. Yet Spring Turning, like his other images of Iowa, presents an optimistic, inviting landscape in contrast to his difficult childhood on the farm with a distant and reserved father. Much has been made of the fact that this painting was done during the artist’s four-year marriage to Sara Sherman Maxson, and after the death of his mother Hattie, to whom he was immeasurably devoted. Wanda Corn and other critics read the landscape of Spring Turning as a reclining female nude, or as a large patchwork quilt draped over a female body (Corn 90). More recent scholars including Robert Hughes, Henry Adams, and Tripp Evans assert that Grant Wood was a closeted homosexual; Evans suggests that this image is “the most erotically charged landscape Wood ever created,” and that these same fields suggest “a man’s body, rather than the reclining figure of an earth goddess” that Wanda Corn suggested (see Tripp R. Evans, Grant Wood: A Life, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2010, 235). Although never discussed in these specific terms during Wood’s lifetime, it seems interesting that this was created during the period when the artist Georgia O’Keeffe was angrily rejecting critical readings of her large-scale flowers as sexual imagery. Instead what the contemporary critic Henry McBride wrote of the painting in “Wood’s Satire”, The New York Sentinel, October 1936, was:

“He paints a Spring Plowing (sic) in which the hills resolve, under the plowman’s touch, into vast checkerboard squares that are highly ridiculous. That is making fun of nature. Artists should not do that. It is all very well to poke fun at the Daughters of Revolution but you can’t do that to anything so (sic) serious as spring plowing.” (Evans 239)

Grant Wood may not have been a farmer, but he was an artist who grasped the agrarian mindset and practices of his fellow Iowans. In this image, the farmers plow their land using a farrow hoe behind the team. In Wood’s incomplete and unpublished autobiography (ghostwritten by Park Rinard) Return from Bohemia: A Painter’s Story. Wood recollected that as a young boy, “I liked to stand on a crest of a hill and watch father or Dave Peters plowing in a field below. They guided the plow parallel to the sides of the rectangular field and progressed concentrically inward, cutting great square patterns with light stubble centers” (Evans 237).

Wood’s metaphor of man both shaping and being shaped by his landscape is one that was particularly important as this decade saw the ravaged, overworked soil of the Midwest blown away in the Dust Bowl. As a matter of fact, this paean to the land’s fertility was painted during the same year that the composer Virgil Thomson wrote the film score for The Plow that Broke the Plains, a federal film documenting the farming practices that were believed to have caused the Dust Bowl. Thus any reading of the forms in this image as anthropomorphic reflecting the sexual desires of the artist should exist alongside a more straightforward if sentimental homage to Wood’s Arcadian vision, a visual affirmation of the basic agrarian character and values of Iowans (and by extension Americans) that could see them through any hard times.

ProvenanceFrom 1936 to 1937

Maynard Walker Gallery, New York. [1]

From 1937 to 1943

Alexander Woollcott (1887-1943), purchased through Maynard Walker Gallery, New York as an agent for the artist in 1937. [2]

From 1946

Mrs. Elon H. Hooker, purchased from Maynard Walker Gallery, New York on May 14, 1946. [3]

To 1977

Elon Marquand (b. 1943), Yarmouthsport, MA. [4]

From 1977 to 1978

James Maroney, Inc., New York, purchased from Elon Marquand November 4, 1977. [5]

From 1978 to 1991

Barbara B. Millhouse, New York, purchased from James Maroney, Inc., New York January 20, 1978. [6]

From 1991

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC, given by Barbara Millhouse November 26, 1991. [7]

Notes:

[1] James Maroney, Jr. "Hiding in Plain Sight: Decoding the Homoerotic and Misogynistic Imagery of Grant Wood,"

[2] See note 1.

[3] Letter and Bill-of-Sale from Maynard Walker to Mrs. Elon H. Hooker dated May 14, 1946.

[4] Email correspondence with James H. Maroney, Jr. August 13, 2010.

[5] See note 4.

[6] See note 4.

[7] Deed of Gift, Object Files, Reynolda House Museum of American Art.

Exhibition History1936

The 1936 International Exhibition of Paintings

Carnegie Institute, Pittsburgh PA

Cat no. 110.

1936

Maynard Walker Gallery, New York NY (9/1936)

Grant Wood 1891-1942: A Retrospective Exhibition

The University of Kansas, Lawrence KS

Cat. no. 40.

1978-1979

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York NY

1983-1984

William Carlos Williams and the American Scene

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York NY (6/5/1983-9/4/1983)

The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago IL (1/21/1984-4/15/1984)

Minneapolis Institute of Fine Arts, Minneapolis MN (9/25/1983-1/1/1984)

M. H. DeYoung Memorial Museum, San Francisco CA (5/12/1984-8/15/1984)

Cat. no. 50

1995-1996

Grant Wood: An American Master Revealed

Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha NE (12/10/1995-2/25/1996)

2000

Illusions of Eden: Visions of the American Heartland

Columbus Museum of Art, Columbus OH (2/18/2000-4/30/2000)

2006-2007

The Modern West: American Landscapes, 1890-1950

Museum of Fine Arts, Houston TX (10/29/2006-1/28/2007)

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles CA (3/4/2007-6/3/2007)

2016

Grant Wood and the American Farm

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winton-Salem, NC (9/9/2016-12/31/2016)

2018

Grant Wood: American Gothic and Other Fables

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY (3/2/2018 - 6/10/2018)

2021

The Voyage of Life: Art, Allegory, and Community Response

Reynolda House Museum of American Art (7/16/2021 - 12/12/2021)

Published References“21 Artists with 21 Works Honor an Art Dealer.” The Art Digest. (Dec. 1, 1936): 17.

“Grant Wood’s Lastest Landscape ‘Spring Turning." LIFE (Feb. 8, 1937): 34-35.

Craven, Thomas. “Grant Wood.” Scribner’s. (June 1937): 21-22.

The London Studio. (Sept. 1937): 162.

Hall, W. S. Eyes on America: the United States as seen by her artists. 1939.

Garwood, Darrell. Artist in Iowa: A life of Grant Wood. 1944.

Gombrich, Ernest. “Experimental Art.” The Story of Art. 1951.

Dennis, James M. Grant Wood: A Study in American Art and Culture. 1975.

Yale University Press, Art and Architecture. 1983.

“American Renewal.” Time Magazine. (Feb. 23, 1981): 38-39.

Time Magazine. (Jun. 27, 1983): 68.

LIFE. (Sept. 1983): 60.

Cather, Willa. “The Troll Garden.” 1984.

"Wright Morris’s Nebraska." Great Plains Quarterly. (Winter 1987): 18.

Grant Wood: An American Master Revealed. Davenport IA: Davenport Museum of Art, 1995.

Carroll, Colleen. Earth, Air, Fire, Water: How Artists See the Elements. New York: Abbeville Press, 1995.

Duggleby, John. Grant Wood: Artist in Overalls. Seattle: Marquand Books, 1995.

Gombrich, Ernest. The Story of Art. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 1995.

Senzoku, Nobuyuki. New History of World Art. 26 Tokyo: Shogakukan, 1995.

Kinsey, Joni Louise. Plain Pictures: Images of the American Prairie. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1996.

Dennis, James M. Renegade Regionalists: The Modern Independence of Grant Wood, Thomas Hart Benton, and John Steuart Curry. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1998.

Living in Our World: The Americas. Raleigh, NC: Humanities Extension/Publications Program North Carolina State University, 1998.

Beckett, Wendy. Sister Wendy’s American Masterpieces. New York: Dorling Kindersley, 2000: 120-121.

Hubbard, Guy. "Teaching Art with Art: Making an Entrance,"Arts and Activities 129 no. 2 (March 2001): 42-43.

Dross, Erika. Twentieth-Century American Art. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Allen, Dick. The Day Before: New Poems. Sarabande Books, 2003.

Georgia O’Keeffe visions of the sublime / edited by Joseph S. Czestochowski. Memphis: Torch Press and International Arts, 2004.

Boyer, Paul. The Enduring Vision: a history of the American people. Houghton Mifflin, 2005.

Knutson, Anne Classen. Andrew Wyeth : memory & magic / Anne Classen Knutson ; introduction by John Wilmerding ; essays by Christopher Crosman, Kathleen A. Foster, Michael R. Taylor. Atlanta: High Museum of Art, 2005. ISBN: 0847827712

Neff, Emily Ballew. The Modern West: American Landscapes, 1890-1950. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006. ISBN: 0300114486

Beckett, Wendy. Sister Wendy on Prayer. London: Continuum Books, 2007.

Evans, Tripp R. Grant Wood: a life. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2010. ISBN: 9780307266293

Barrett, Terry. Making art: form & meaning. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2011. ISBN: 9780072521788

Kairyudo, Shuppan. Unknown textbook. April 2012.

Speer, George V. Things of the Spirit: Art and Healing in the American Body Politic, 1929-1941. Peter Lang Publishing, 2012.

Granier, Fabien. "Des Hommes et des Ornieres," Billebaude: Ruralité, Quel Héritage?, no. 6, (Spring-Summer 2015): 20-21.

Doss, Erika. American Art of the 20th-21st Centuries. New York: Oxford University Press, 2017. pg. 111.

Haskell, Barbara. Grant Wood: American Gothic and Other Fables. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 2018. pg. 162-163.

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Reynolda: Her Muses, Her Stories, with contributions by Martha R. Severens and David Park Curry (Winston-Salem, N.C.: Reynolda House Museum of American Art affiliated with Wake Forest University, 2017). pg 226, 227

Stratton, Shannon R., ed. Roger Brown: Virtual Still Lifes. New York: Museum of Arts and Design, 2019, pg. 51.

Maroney, James H. Jr., Fresh Perspectives on Grant Wood, Charles Sheeler, and George H. Durrie. Leicester, VT: Gala Books, Ltd, 2019, pg 65.

Pearson, Harry. "Hidden in Plain Sight." Christie's Magazine, 2019. pg. 77

Taylor, Sue. Grant Wood's Secrets. Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2020, pg 157.