Skip to main content

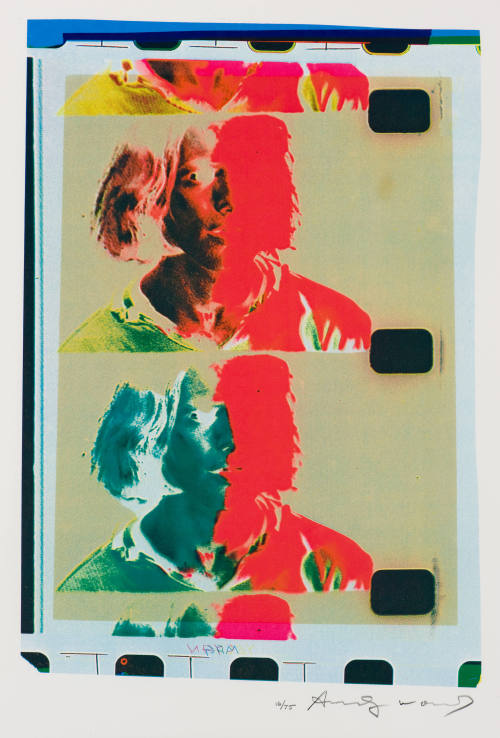

Eric Emerson (Chelsea Girls), a silkscreen, is dominated by two frames from Warhol’s highly successful 1966 film, Chelsea Girls. The face and shoulders of Emerson are repeated in jarring complementary colors of intense pinkish-red and yellowish-green. Cut off at the bottom is the top of his head, and at the top of the image is his upper torso, also cropped, suggesting continuity and repetition, hallmarks of Warhol’s style. The slightly lopsided image is punctuated along the top, bottom, and right side with rounded rectangles that represent the sprocket holes by which the film is pulled through the projector.

Like many of Warhol’s films, Chelsea Girls lacked a script. Instead, the youthful Emerson, age twenty-two, improvised a monologue. Handsome and blond, Emerson came from a working-class background like Warhol, and had studied dance and performed with the New Jersey Ballet Company. After giving up dance, he was studying cosmetology, and living with his eighteen-year old wife when he met Warhol. In an interview he openly discussed his sexuality: “My father thinks I’m a little sweet,” he said, “because I let my hair grow long. What he don’t understand is that my generation can swing both ways. The last time I saw my father, I walked up to him and said, ‘Hi, Pop,’ and he hit me in the mouth with a closed fist.” [1]

Similarly, Chelsea Girls garnered unfavorable reviews from the popular press. Time labeled it “Cecil B. DeSade of underground cinema…a very dirty and very dull peep show. There is space for this kind of thing, and it is definitely in the underground, like a sewer.” The New York Times called it a “travelogue of hell—a grotesque menagerie of lost souls whimpering in a psychedelic moonscape of neon red and fluorescent blue.” [2] Nevertheless, the film, which cost less than three thousand dollars to make, was a box office hit.

The film followed activities that happened in eight rooms of the Chelsea Hotel. Warhol’s methodology encouraged spontaneity from his untrained actors. “I leave the camera running until it runs out of film, because that way I can catch people being themselves instead of getting up a scene and shooting it.” Because Warhol disliked editing, he ended up with a lot of footage, shot half in color and half in black and white, so he decided to run two reels at the same time. “By projecting two reels simultaneously, we were able to cut down the running—projecting—time in half, avoiding the tedious job of having to edit such a long film. After seeing the film projected in the split screen format, I realized that people could take in more than one story or situation at a time.” [3] This duality is apparent in the silkscreen, with its split figures and repeated images. The lack of a professional cast, the crude production techniques, and the quasi-pornographic subject in many of his films may be viewed as Warhol’s satire of that quintessentially American phenomenon and celebrity machine: Hollywood.

Notes:

[1] Emerson, quoted in David Bourdon, Andy Warhol (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1989), 228.

[2] “Notes from the Underground,” Time, 1966, 37, and Dan Sullivan, “Andy Warhol’s Chelsea Girls at the Cinema Rendezvous,” New York Times, December 2, 1966.

[3] Warhol, quoted in Bourdon, Andy Warhol, 240, and Warhol, quoted in Gerard Malanga, “A Conversation with Andy Warhol,” The Print Collector’s Newsletter, January–February 1971, reprinted in Kenneth Goldsmtih, I’ll Be Your Mirror: The Selected Andy Warhol Interviews, 1962–1987 (New York: Carroll & Graft, 2004), 193.

ProvenanceFrom 1984

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC, given by the American Art Foundation through The Pace Gallery, New York on March 20, 1984. [1]

Notes:

[1] Letter, March 20, 1984, object file.

Exhibition History2006

Self/Image: Portraiture from Copley to Close

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC (8/30/2006-12/30/2006)

2021

The Voyage of Life: Art, Allegory, and Community Response

Reynolda House Museum of American Art (7/16/2021 - 12/12/2021)

Published ReferencesReynolda House Museum of American Art, Reynolda: Her Muses, Her Stories , with contributions by Martha R. Severens and David Park Curry (Winston-Salem, N.C.: Reynolda House Museum of American Art affiliated with Wake Forest University, 2017). pg. 206, 207

DepartmentAmerican Art

Eric Emerson (Chelsea Girls)

Artist

Andy Warhol

(1928 - 1987)

Date1982

Mediumsilkscreen on Somerset White paper

DimensionsFrame: 32 1/2 x 25 1/16 in. (82.6 x 63.7 cm)

Paper: 29 3/4 x 22 1/4 in. (75.6 x 56.5 cm)

Image: 19 1/4 x 13 1/4 in. (48.9 x 33.7 cm)

SignedAndy Warhol

Credit LineGift of the American Art Foundation

Copyright© 2021 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Object number1984.2.1.j

DescriptionFascinated by movie stars from the time he was six-years-old, Andy Warhol became enamored with making his own films after he bought a sixteen-millimeter Bolex camera in 1963. He was as unconventional and inventive in his films as he was in his paintings and prints. But instead of seeking out movie stars and celebrities for his films as he had done in his art, he formed his amateur casts and ordinary sets from his immediate world. Eric Emerson (Chelsea Girls), a silkscreen, is dominated by two frames from Warhol’s highly successful 1966 film, Chelsea Girls. The face and shoulders of Emerson are repeated in jarring complementary colors of intense pinkish-red and yellowish-green. Cut off at the bottom is the top of his head, and at the top of the image is his upper torso, also cropped, suggesting continuity and repetition, hallmarks of Warhol’s style. The slightly lopsided image is punctuated along the top, bottom, and right side with rounded rectangles that represent the sprocket holes by which the film is pulled through the projector.

Like many of Warhol’s films, Chelsea Girls lacked a script. Instead, the youthful Emerson, age twenty-two, improvised a monologue. Handsome and blond, Emerson came from a working-class background like Warhol, and had studied dance and performed with the New Jersey Ballet Company. After giving up dance, he was studying cosmetology, and living with his eighteen-year old wife when he met Warhol. In an interview he openly discussed his sexuality: “My father thinks I’m a little sweet,” he said, “because I let my hair grow long. What he don’t understand is that my generation can swing both ways. The last time I saw my father, I walked up to him and said, ‘Hi, Pop,’ and he hit me in the mouth with a closed fist.” [1]

Similarly, Chelsea Girls garnered unfavorable reviews from the popular press. Time labeled it “Cecil B. DeSade of underground cinema…a very dirty and very dull peep show. There is space for this kind of thing, and it is definitely in the underground, like a sewer.” The New York Times called it a “travelogue of hell—a grotesque menagerie of lost souls whimpering in a psychedelic moonscape of neon red and fluorescent blue.” [2] Nevertheless, the film, which cost less than three thousand dollars to make, was a box office hit.

The film followed activities that happened in eight rooms of the Chelsea Hotel. Warhol’s methodology encouraged spontaneity from his untrained actors. “I leave the camera running until it runs out of film, because that way I can catch people being themselves instead of getting up a scene and shooting it.” Because Warhol disliked editing, he ended up with a lot of footage, shot half in color and half in black and white, so he decided to run two reels at the same time. “By projecting two reels simultaneously, we were able to cut down the running—projecting—time in half, avoiding the tedious job of having to edit such a long film. After seeing the film projected in the split screen format, I realized that people could take in more than one story or situation at a time.” [3] This duality is apparent in the silkscreen, with its split figures and repeated images. The lack of a professional cast, the crude production techniques, and the quasi-pornographic subject in many of his films may be viewed as Warhol’s satire of that quintessentially American phenomenon and celebrity machine: Hollywood.

Notes:

[1] Emerson, quoted in David Bourdon, Andy Warhol (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1989), 228.

[2] “Notes from the Underground,” Time, 1966, 37, and Dan Sullivan, “Andy Warhol’s Chelsea Girls at the Cinema Rendezvous,” New York Times, December 2, 1966.

[3] Warhol, quoted in Bourdon, Andy Warhol, 240, and Warhol, quoted in Gerard Malanga, “A Conversation with Andy Warhol,” The Print Collector’s Newsletter, January–February 1971, reprinted in Kenneth Goldsmtih, I’ll Be Your Mirror: The Selected Andy Warhol Interviews, 1962–1987 (New York: Carroll & Graft, 2004), 193.

ProvenanceFrom 1984

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC, given by the American Art Foundation through The Pace Gallery, New York on March 20, 1984. [1]

Notes:

[1] Letter, March 20, 1984, object file.

Exhibition History2006

Self/Image: Portraiture from Copley to Close

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC (8/30/2006-12/30/2006)

2021

The Voyage of Life: Art, Allegory, and Community Response

Reynolda House Museum of American Art (7/16/2021 - 12/12/2021)

Published ReferencesReynolda House Museum of American Art, Reynolda: Her Muses, Her Stories , with contributions by Martha R. Severens and David Park Curry (Winston-Salem, N.C.: Reynolda House Museum of American Art affiliated with Wake Forest University, 2017). pg. 206, 207

Status

Not on view